Installation view of ‘William Kentridge: that which we do not remember’ exhibition, on display 8 September 2018 – 3 February 2019, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. © William Kentridge Photo: Christopher Snee, AGNSW

Described as ‘one of the most distinctive and powerful voices in contemporary art’ by the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW), South African artist William Kentridge has been honoured with a solo exhibition at the gallery.

What perhaps makes this a little different than other big name shows, is that Kentridge himself curated the exhibition – not just a “that goes there”, but the whole theatrical presentation, complete with floating scrims, blackened Portuguese cork-walled video ”huts”, staged wicker chairs and a “recreation” of his studio.

The design of the show has a huge impact – as does the work itself – and is the latest in a long line of collaborations with Brussels-based designer Sabine Theunissen, who has worked with Kentridge since 2005 to create many of his theatre-based projects.

Kentridge worked with designer Sabine Theunissen to create a bespoke narrative across the AGNSW’s exhibition. Photo: ArtsHub

But as the shopping ad goes, “wait, that’s not all”. You also get an incredible collaboration with arts patron Naomi Milgrom, who loaned a large number of works for the exhibition and was intimately involved in its planning.

Milgrom also supported The Head & the Load: William Kentridge, a world premiere performance at Tate Modern, London, in July this year.

Australian support for Kentridge’s work is undeniably strong. Perhaps it has something to do with a shared colonial heritage, or our passion to share a yarn?

Another gong for this show is the unveiling of a major gift to the AGNSW collection by Anita Belgiorno-Nettis AM and Luca Belgiorno-Nettis AM – Kentridge’s eight channel video, I am not me, the horse is not mine (2008), which was commissioned by curator Carolyn Christov-Bakagriev for the 16th Biennale of Sydney at Cockatoo Island.

Further gifts by Ruth Faerber, Walking man (2000), and Gretel Packer’s long-term loan of Second-hand reading (2013) also feature in the exhibition.

And to top off Kentridge’s “Australian festival de jour”, Annandale Galleries (one of Kentridge’s few galleries globally) opened an exhibition to coincide with the AGNSW’s exhibition, while Opera Australia are preparing for the premiere of the Kentridge-directed Wozzeck in January 2019.

The Opera company writes: ‘Kentridge’s haunting illustrations offer a window into the carnage of Wozzeck’s world. Charcoal drawings fill the stage, frenetic scribbles are illuminated and then erased, as we wonder, with Wozzeck, what is real.’

Kentridge has long had a love affair with opera – works in the AGNSW exhibition are inspired by The Nose and The Magic Flute. In fact, Kentridge flew into Sydney directly from the premiere of his production of The Magic Flute, which opened with bold animated projections at The New National Theatre in Tokyo this week.

The earliest work in the exhibition, Drawing for Woyzeck on the Highveld (1992) is a charcoal study from Kentridge’s first collaboration with Handspring Puppet Company, and presented here in the re-creation of his studio.

Installation view of William Kentridge: That which we do not remember on display from 8 September 2018 – 3 February 2019, at the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Photo: ArtsHub

What of the work?

Titled That which we do not remember, the AGNSW exhibition pulls together 32 significant works spanning across 15 years of Kentridge’s rich career and capturing his signature style, moving elegantly and eruditely across mediums – from sculpture to film, charcoal drawings to collage, sound through to tapestry.

The title alludes to notions of erasure and memory and the kind of alchemy that exists in materials, echoed in Kentridge’s own words: ‘The primary lie of all art is that you know it is an illusion even while you fool yourself.’

The artist made particular note of two deliberate curatorial choices. Upon entering the exhibition viewers are faced with the title work, That which we do not remember (2017) – a collage of woodblock prints pinned within a frame. He said the work was the result of a gap in a long parade of figure – a void that only later, having his “ah ha moment”, Kentridge realised was connected to Malevich’s iconic Black Square (painting) 1915 – which happens to be hanging upstairs from Kentridge’s show on loan from the Hermitage Museum.

That which we do not remember is somewhat overlooked as the visitor’s eye is quickly pulled to what Kentridge has described as an “evoking of his private studio”, giving audiences rare insights into his working methods (pictured above).

‘As a creator, you need to be in a safe space. So the space within the artistic sphere is where it is understood that everything is a possible construction, and construction of the world rather than a revelation of the world,’ Kentridge said.

This space is particularly beautiful in its attention to detail and hanging hardware – particularly exquisite was the framed drawings and studies present on easel-like tables.

The exhibition space had a deeply physical impact – moving from light to dark spaces, from intimate works that hone our vision to grand gestures, from the smell of charred cork to the lightness of floating muslin.

Growing a tree (2013) is sure to be popular with audiences, as will as the epic collage A drawing as big as the world (2003). The inclusion of Kentridge’s tapestry Tableau des Finances et du Commerce de la partie Francoise de S. Domingue (2011), and a number of his quirky sculptures, stitch this exhibition together beautifully.

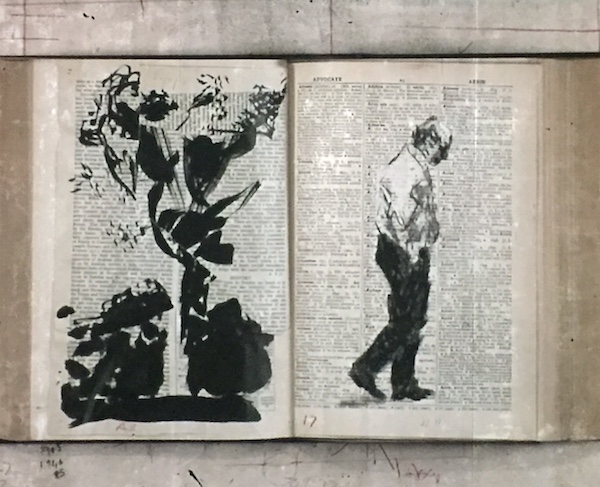

While it is hard to label Kentridge’s work as overtly political, there is a sensitivity that touches on his experiences of the apartheid regime in South Africa, such as the flip-book animation Second-hand reading (2013) – also referred to as “the prisoner in the book” for its loose echo of the story of a political prisoner pacing out his days in his cell.

Detail of Second-hand reading (2013), flip-book film; on long-term loan to AGNSW by Gretel Packer. Photo: ArtsHub.

‘The work is technically not a flip book but is made through projected drawings of a pacing figure onto filmed pages of a book being turned, rather than figures actually being drawn on these pages,’ explained Kentridge.

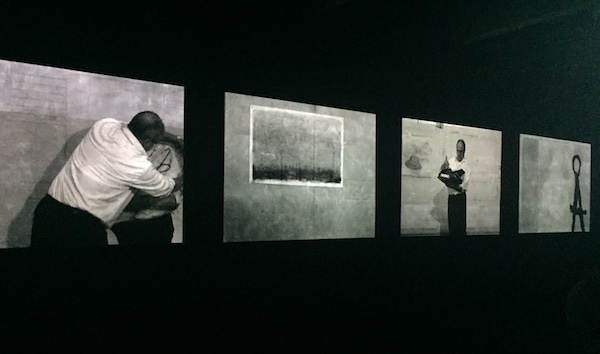

Another gem is within Kentridge’s nine channel homage to early cinema pioneer, Georges Méliès, titled 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, Day for Night and Journey to the Moon (2003), a film run in reverse in which the artist reconstitutes a portrait of himself.

Detail of nine channel video, 7 Fragments for Georges Méliès, Day for Night and Journey to the Moon (2003). Photo: ArtsHub.

He made this piece while working on his production of The Magic Flute – again music, theatre, film and drawing seamlessly fuse into one.

AGNSW Director, Michael Brand, got it right when he said that the exhibition offers ‘an opportunity to be immersed in the work of one of the world’s most celebrated living artists.’

This exhibition is a great celebration of creative engagement and its capacity to dovetail into every aspect of life – it is a true lesson for us all.

Rating: 5 stars ★★★★★

William Kentridge: that which we do not rememberArt Gallery of NSW

Domain Road, Sydney

8 September 2018 – 3 February 2019