Emotional agony and doomed, unconsummated love dredge up painful memories of school discos and Clearasil. These are its themes but there is nothing remotely adolescent about The Enchantment, Victoria Benedictsson’s semi-autobiographical play about the fatal consequences of a woman’s love for a selfish sculptor in the Parisian art world of the 1880s.

Benedictsson was devastated by the sexual and artistic rejection of Danish critic Georg Brandes with whom she had a high-profile affair. Brandes refused to take her writing seriously because she was a woman. On 21st July 1888, a few months after completing The Enchantment, she cut her own throat in a Copenhagen hotel room.

Benedictsson’s heroine, Louise Strandberg (Nancy Carroll), is not an artist but an invalid with no vocation or work of any kind who pours all of her being into her love for Gustave Alland (Zubin Varla). Louise’s friend, Erna Wallden (Niamh Cusack), herself a rejected lover of Gustave’s is able to sustain herself through her painting and even to grow in stature after her disappointment. Being an artist saves Erna whereas being the object of an artist’s passing passion is the death of Louise. A bitter irony for Victoria Benedictsson herself.

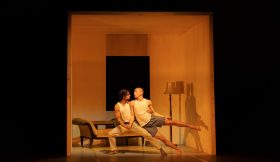

Clare Bayley’s new version of the play, directed by Paul Miller, is in the round in the Cottesloe and all the better for it. Period drama is usually a vast enterprise involving massive sets, scores of extras and compulsory use of the word “lavish”. In Miller’s intimate production, the immaculately tailored costumes and the wonderful lighting by Bruno Poet are the set. It is a thrilling experience to be close enough to touch the cast in such an emotionally charged piece.

Working with the audience on four sides is challenging and requires creative use of diagonal sightlines by the actors. Occasionally this constraint can cause some clunky two-handers where one actor takes the role of “yolk” and the other of “white” in a slowly revolving “fried egg formation” on stage.

Louise spends very little time offstage and Nancy Carroll is so beautiful that it becomes hard to understand how Gustave could possibly want to leave her. Zubin Varla’s charisma and aquiline, brooding features save Gustave from being purely a hate figure and their scenes together in the first half are amongst the best in the play. Lesser actors would struggle to inject any sexual tension into their complex dialogue, rich in dense metaphors, but they succeed. The distance the staging obliges them to keep from each other only adds to the chemistry and makes the tender tableau at the beginning of Act 4, after the relationship has been consummated, all the more intimate.

Strong supporting performances prevent the piece from being top heavy. Niamh Cusack is superb; entirely avoiding one-dimensional “woman scorned” whilst Hugh Skinner rescues the role of Louise’s stepbrother, Viggo, who is little more than a cipher on the page.

It should be hard, in the twenty first century, to connect with the esoteric conversations of artists in 1880s Paris. Their musings on metaphysics and morality ought to be as tiresome and trite as a pub argument between philosophy students. We could be expected to find it faintly ludicrous that a woman would drown herself after being “dumped”. None of these difficulties arise. The world conjured by Benedictsson and Bayley is one where people talk about things that matter and tell the truth.

To enchant is to charm, bewitch or delight and that is what the play does.

The Enchantment runs until 1 November 2007 at The National Theatre.