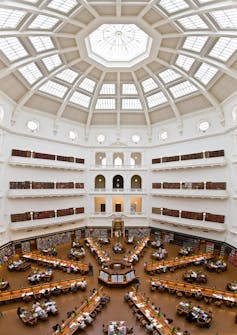

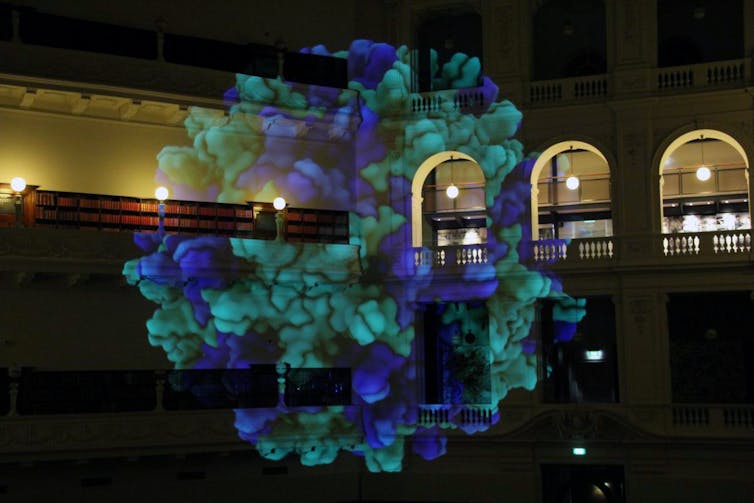

The State Library of Victoria all lit up for White Night Festival 2015 to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Alice in Wonderland. Image supplied.

Last year two Danish librarians – Christian Lauersen and Marie Eiriksson – founded Library Planet: a worldwide, crowdsourced, online library travel guide. According to them, Library Planet is meant to inspire travellers “to open the awesome book that is our world of libraries, cities and countries”.

The name of the online project is a deliberate nod to the Australian-made Lonely Planet. The concept is simple and powerful. Library lovers contribute library profiles and images from their travels; the founders then curate and publish the posts, with the ambition of capturing library experiences and library attractions from around the world.

Why make libraries a focus of travel? There are a thousand practical and aesthetic reasons, as well as cultural ones. Libraries for the most part are safe and welcoming places. And they tell unique stories about the people who build and appreciate them. If books are the basic data of civilisation, then nations’ libraries provide windows on national souls. They are precious places in which to seek traces of the past, and reassurance about the future.

Library Planet now has dozens of intriguing profiles – including from Burma, Iceland, Tanzania and French Polynesia. A recent entry celebrated the Melbourne Cricket Club library at the MCG. The site has rapidly become a favourite among the bibliographical communities and subcultures of Instagram and Twitter, such as #rarebooks, #amreading and #librarylove.

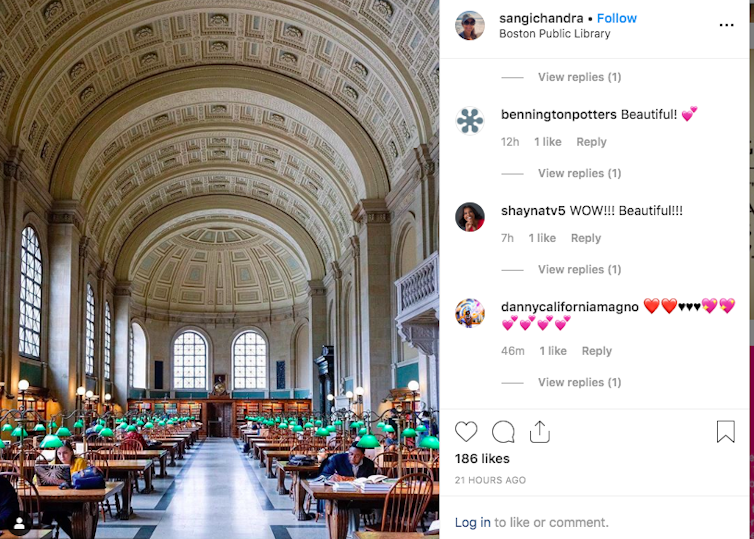

The hashtag #librarylove is popular on Instagram.

The Grand Tour – of libraries

Library Planet may be new, but library tourism has been around a long time. In the Western Renaissance, Italian humanists visited derelict monastic libraries throughout Europe to rescue the unique manuscripts that had fallen into mouldy neglect in the late Middle Ages. In the 18th century, old libraries were a focus of the Grand Tour, and the subject of a rich travel literature.

Not all visits went smoothly. The author and historian Friedrich Hirsching called the directors of Germany’s public libraries “arrogant misanthropes who look upon their positions as sinecures”.

Radcliffe Camera, a part of Oxford University’s Bodleian Library, and All Souls College to the right, in Radcliffe Square, looking north from the tower of St Mary’s Church. Tejvan Pettinger/Wikipedia Commons

Well into the 19th century, people were still touring libraries and they were still rescuing manuscripts. In 1843, the bibliographer Obadiah Rich wrote to the bibliophile Sir Thomas Phillipps:

‘More manuscripts are destroyed by ignorant people than by civil wars. I once found a bookseller at Madrid occupied in taking off the parchment covers from a large pile of old folios and throwing them into his cellar to sell by weight to the grocers: I opened one, and immediately bought the whole (120 volumes) at about two shillings per volume: you will hardly believe that among them was one of the most precious volumes in your collection; a volume of original documents relating to England in the time of Philip the second!’

The era of the biblio-treasure hunt extended, Indiana-Jones style, into the 20th century. In the spring of 1910, villagers were digging for fertiliser at the site of the destroyed Monastery of the Archangel Michael, in Egypt’s Fayyum oasis, near present-day Hamuli. In an old stone cistern the villagers found 60 Coptic manuscripts. Evidently, early in the tenth century, the monks had buried the monastery’s entire library for safekeeping, shortly before the monastery closed for good.

Written in Sahidic (a Coptic dialect) and ranging in date from 823 to 914 AD, the manuscripts formed the oldest, largest and most important group of early Coptic texts with a single provenance.

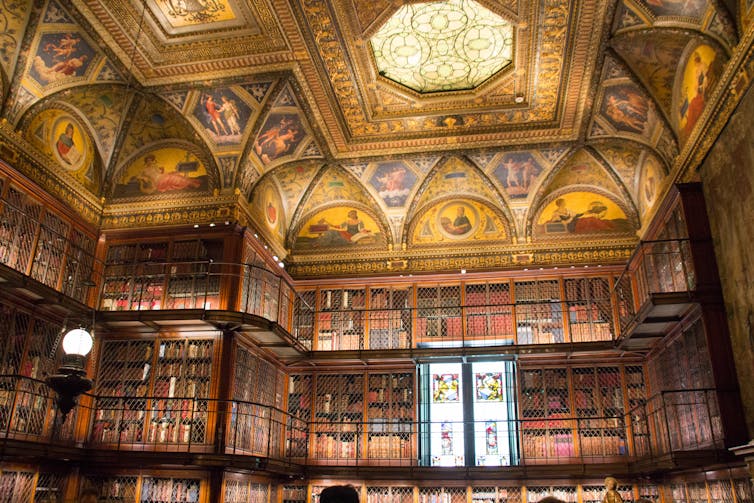

Dealers and bibliographers relished the discovery. Soon the illustrious American banker and bibliophile J. P. Morgan would buy most of the manuscripts, and they are now among the treasures that visitors can see at New York’s extraordinary biblio-temple, the Morgan Library and Museum.

The Morgan Library and Museum, New York. Wikimedia Commons

A modern pilgrimage to old libraries

In 2017, my wife Fiona and I retraced the steps of some of the first library tourers. With our two young daughters (aged five and one at the time), we visited libraries in Switzerland, such as the spectacular Abbey Library of St Gall (Sankt Gallen), a former monastery, and the handsome Zentralbibliothek in Zurich. In Britain, we called on the Bodleian Library, the Wellcome Library, Lambeth Palace Library, University College Library and the irreplaceable British Library.

Our library touring also took us to North America, Asia, Oceania and major state and regional libraries in Australia. Visiting institutions like the Morgan, the Library of Congress, the Smithsonian Libraries, Harvard’s Widener and Houghton libraries, the New York Public Library, the Boston Public Library, the National Library of Australia, the state libraries of Victoria and NSW and national and university libraries in China and Indonesia and New Zealand; these were life-changing experiences.

A fifth floor view of the Reading Room at the State Library of Victoria. Wikimedia Commons

Which libraries were our favourites? A few institutions stand out as having done everything right: beautiful, welcoming buildings; important and accessible holdings; and internal spaces designed for future scholars as well as current ones. Prominent members of this Goldilocks category include the Boston Athenaeum Library, the NYPL, the Folger Shakespeare Library and its larger Washingtonian neighbours.

In 2018, the four of us embarked on another library tour, this time of Japan. We sought out major libraries and everyday ones. An example from the first category is Japan’s principal public library, the National Diet Library. (The Diet is Japan’s national parliament.) The Tokyo Main Library in Chiyoda, a civic and parliamentary precinct, is the Diet Library’s principal site. It serves members of parliament and is also open to members of the public, who must register before entering.

The building itself features boarded concrete beams, stained glass and chunky tiles. The “high brutalist” style reminded us of a Dr Who set. The library is rich in Japanese and foreign literature, rare books and manuscripts, technical and official volumes and a multitude of other holdings. The total collection numbers in the tens of millions of items, making it one of the world’s largest and most important.

Also in the Chiyoda district, the building that houses the National Archives of Japan is a poignant place that contains Japan’s foundational documents, such as the decree that changed the city of Edo to Tokyo; the documents that returned to Japan its sovereignty after post-war occupation; and those that returned to Japan the ownership of Okinawa.

Children need special permission to enter the Tokyo Main Library – special permission that my daughters did not have. But a few suburbs north of Chiyoda, in the cultural precinct near Ueno Park, is the excellent International Library of Children’s Literature. Visitors can access this library without charge and without a library card.

The International Library of Children’s Literature, in Tokyo. Stuart Kells

Another priority for our visit was on the hilly, green outskirts of Tokyo. A private university, Meisei University is home to the world’s second largest collection of Shakespeare First Folios. (The Folger has by far the largest collection. The New York Public Library and the British Library are among the small number of institutions that also hold multiple copies.) In addition to its cache of First Folios, Meisei also possesses other early Shakespeare editions, and much else of Shakespearean interest including artworks and artefacts.

Kyoto, the former capital of Japan, is a city of libraries. Many of its beautiful old buildings and neighbourhoods have been preserved. Those neighbourhoods are peppered with large and small libraries, such as the Kyoto Library of Historical Documents, the Kyoto Prefecture Library, the Kansai Library (another branch of the National Diet Library) and the glorious temple of pulp: the Manga Museum.

All hail the librarian

So what did we learn from all this library touring? Reports of the death of the library are certainly exaggerated. People, including young people, continue to use and appreciate libraries. People are still investing in libraries, and they are still buying and reading books. But the libraries and their custodians are engaged in hot battles on multiple fronts, including the fight against underfunding and creeping volunteerism, and the epochal clash between analogue and digital content.

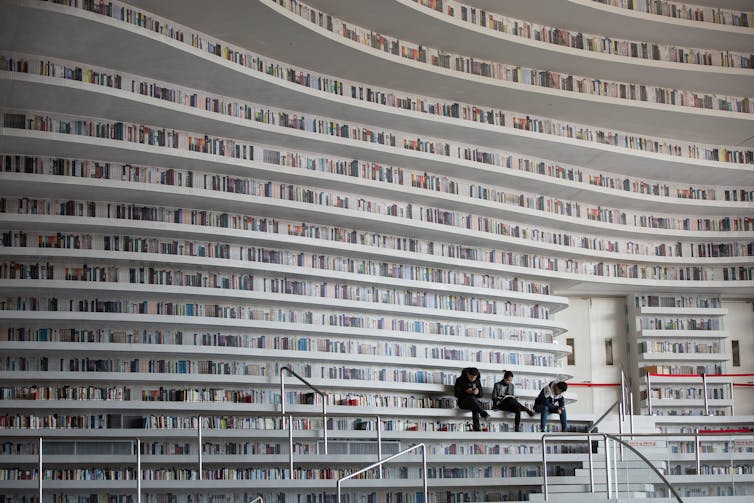

Libraries as physical spaces have been transformed. Library architecture is a wonderful site of experimentation. (Great examples include the new Library of Alexandria, China’s amazing Tianjin Binhai Library, the University of Zurich’s ultra-modern Law Faculty library, and the stylish Melton Library and Learning Hub in Victoria.) Library spaces now permit an expansive variety of uses, including noisy and smelly ones. As welcoming, non-commercial and non-judgemental “third spaces”, libraries are increasingly serving a generous variety of pro-social purposes.

The Tianjin Binhai Library, which is also called ‘The Eye’, opened in 2017. AAP

In their curation and display of books and manuscripts, comics and posters and realia, libraries are telling rich and important stories – about women’s rights, LGBTIQ rights, civil rights, counter-culture movements, climate change and the crimes of history. Libraries and librarians are contributing to social inclusion directly and in practical ways, such as by helping people write their CVs, and by lending ties, handbags and briefcases for job interviews.

In our world of gobbling capitalism and pervasive consumerism, libraries continue to be founded on humanism. The diverse roles of libraries as places of education and participation are becoming more urgent each day. Libraries are part of our knowledge system and our civic and social infrastructure; their accessibility is meant to transcend class, race, gender, sexuality and all the other classifications that elsewhere can divide us. Not everyone, though, has got the memo.

In all the battles about what libraries are for and who can use them, librarians are in the trenches, fighting the good fight. Both on-line and in-world, the latest renaissance of library appreciation has naturally seen much respect and affection directed towards librarians, who for the most part are certainly not “arrogant misanthropes”, and who generally don’t conform to the bookish, shushing stereotype.

But in this new world of library love, librarians also need personal space. They emphatically don’t want random kisses or hugs or cakes. They want you to use their libraries, relish their services, and listen to what their collections and resources say about our collective past, present and future.

If libraries didn’t exist, we’d have to invent them

In the curation and mobilisation of collections and resources, librarians are making the best of our digital future, without discarding our analogue past (though many rightly bemoan the loss of physical card catalogues and the tangible, fractal, serendipitous experiences that came with them).

Rare and fragile books are being digitised on a massive scale; scandalous and hitherto hidden books are being let out; and librarians are helping to curate and navigate the messy, unbounded and uncooperative soup that we call the internet.

Librarians are also welcoming library tourists as well as regular users and other visitors. In 2016, the New York Public Library reportedly hosted 18 million visitors – many of them from other municipalities, states and countries. That same year, the National Library of China, the largest library in Asia, welcomed 5.6 million visitors. Our very own domed library, the wonderful State Library of Victoria, is also among the world’s most visited libraries. According to that institution’s latest annual report, the library hosted precisely 1,937,643 visitors last year, and had more than twice as many on-line interactions.

An installation at The State Library of Victoria during White Night in 2014. The library hosted almost 2 million visitors last financial year. Image via Kerry O’Brien publicity.

Glue or gum?

Is there a downside to all this visiting? Are we just setting up another tension, in which libraries are victims of their own success, and locals compete with tourists for library space and time? Could our best libraries come to resemble parts of Amsterdam and Venice: pseudo-historical theme-parks; mere caricatures of civic spaces, more for tourists than for locals? Could the “social glue” of libraries be replaced by tourists’ discarded chewing gum?

At showcase libraries such as St Gall and the Library of Congress, tourists are in the majority, but those libraries are fully ready for them – and their gum. In our more humble municipal libraries, the library tourists certainly don’t outnumber the locals, but there is definitely tension between the demands of different types of library users. Nevertheless, I’m optimistic about the future, in part because those tensions are exactly what librarians are deft at resolving.

I’m optimistic, too, because of the progressive and truth-telling roles that libraries are increasingly playing. In Japan, the National Library and the National Archives tell candid and affecting stories about Japan and its fraught modern history. In the US and the UK, libraries such as the Houghton and the British Library have infinite potential to be crusty and excluding. But instead, through exhibitions of books, posters, artefacts and artwork, they are telling diverse stories from marginalised voices about the fight for fairness and social inclusion. These are stories and voices that everyone should hear.

Who exactly are libraries for? Much of the history of libraries is concerned with matters of access. In British and European libraries, for example, people have been shut out at different times based on their gender, class, age, nationality and religion. Each of these exclusions has been, in its turn, the subject of hot debate. But all the arguments have landed us in a good place: today’s library ethos of openness and welcome.

The modern library is a humanist project, founded on inclusion rather than division. Today, it is possible for libraries to be islands of humanity. In the future, if we are unlucky, they might become its warehouses. But with luck, they’ll be its wellsprings.![]()

Stuart Kells, Adjunct Professor, College of Arts, Social Sciences and Commerce, La Trobe University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.