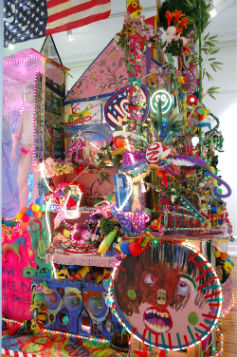

Everything is Fucked by Paul Yore (detail above, full work below). Courtesy of the artist and Neon Parc. Image appears with permission of the photographer, Devon Ackermann.

Contemporary artist Paul Yore was charged with (and ultimately acquitted of) a charge of producing child pornography and a charge of possessing child pornography, as a result of his installation at the Linden Centre for Contemporary Art in 2013, entitled Everything Is Fucked 2013. He is one of a small number of Australian artists to have been charged with a criminal offence as a result of their art, a group that includes Mike Brown, the artist to which Paul Yore was paying homage by the work in question.

This case note discusses the criminal trial of Paul Yore and the Magistrate’s decision: Johnson v Yore.[i] It focuses in particular on the issues the decision raises regarding the role of the right to freedom of expression in criminal prosecutions arising from artistic endeavours; the extent to which artificial images (such as collage) can constitute child pornography; and the authority of the police to excise images from an artistic work pursuant to a search warrant.

The ‘Everything is Fucked 2013’ installation

Paul Yore is a 25 year old emerging contemporary artist, whose work was described during the trial by Max Delany, Senior Curator (Contemporary Art) at the National Gallery of Victoria, as ‘characterised by an interest in and exploration of sexual identity and cultural politics, the excesses of consumer culture, and the influence of capitalism on subjectivity’.

Yore’s installation Everything is Fucked 2013 formed part of ‘Like Mike’, a series of five exhibitions in tribute to artist Mike Brown, who was successfully prosecuted for obscenity in the 1960s. Yore’s installation was exhibited at the Linden Centre for Contemporary Art in St Kilda, Victoria. It was described by the Magistrate as a ‘large-scale psychedelic, cavernous sculptural installation’ in the front room of the Linden. In a review published in Frieze, the work was described as ‘a type of cubby house, whose every surface is cluttered – with toy dolls rearranged to appear engaged in anal sex, colourful beads, dildos, spinning records, rotating objects, flashing lights, silver foil, Justin Bieber posters, children’s musical instruments and hand-painted signs – with a vast network of allusions to queer identity across and between everyday objects’.[ii]

Shortly after ‘Lik e Mike’ opened at the Linden, Victoria Police received complaints about its content from at least one member of the public. Officers of Victoria Police attended and executed a search warrant at the gallery. The police used a Stanley knife to cut seven photographic images from the installation, and subsequently charged Paul Yore with two charges in respect of those seven images – a charge of producing child pornography contrary to section 68(1) of the Victorian Crimes Act 1958, and a charge of possessing child pornography contrary to section 70(1) of that Act.

e Mike’ opened at the Linden, Victoria Police received complaints about its content from at least one member of the public. Officers of Victoria Police attended and executed a search warrant at the gallery. The police used a Stanley knife to cut seven photographic images from the installation, and subsequently charged Paul Yore with two charges in respect of those seven images – a charge of producing child pornography contrary to section 68(1) of the Victorian Crimes Act 1958, and a charge of possessing child pornography contrary to section 70(1) of that Act.

The offence of producing child pornography carried a maximum penalty of 10 years’ imprisonment. The charge of possessing child pornography carried a maximum penalty of five years’ imprisonment. A finding of guilt in relation to one or both of the offences results in the mandatory registration of the offender pursuant to the provisions of the Sex Offenders Registration Act 2004 (Vic).

The criminal trial

Paul Yore pleaded not guilty to both charges.

A central question during the two day trial, which took place in August 2014, was whether each of the seven excised photographic images constituted child pornography, which is defined in section 67A of the Crimes Act to mean ‘a film, photograph, publication or computer game that describes or depicts a person who is, or appears to be, a minor engaging in sexual activity or depicted in an indecent sexual manner or context’. A ‘minor’ is defined by the same section to mean a person under the age of 18 years.

Each image was a collage constructed from multiple photographic images. Photographs of faces of male children were pasted over the heads of adult male bodies in naked or near naked poses, with ‘Pokemon’ stickers covering the genitals. Two of the images depicted fellatio.

In the event that any of the images were found by the court to constitute child pornography, the Defence raised two statutory defences.

The first was the ‘classification defence’ contained in sections 68(1A) and 70(2)(a) of the Crimes Act, which relevantly provided that it was a defence to a prosecution of producing or possessing child pornography to prove that the photograph or publication had, or would have, received a classification other than RC or X or X18+ under the Commonwealth Classification (Publications, Film and Computer Games) Act 1995.

The second was the ‘artistic merit’ defence contained in section 70(2)(b) of the Crimes Act, which provided that it was a defence to a prosecution of possessing (but, somewhat inexplicably, not to a prosecution of producing) child pornography, to prove that the photograph or publication possessed ‘artistic merit’. The term ‘artistic merit’ was not, and is not, defined in the Crimes Act.

The Prosecution called evidence from the Director of Linden, the Chair of the Board of Linden, and the police informant.

The Defence called evidence from three expert witnesses to establish the artistic merit of Paul Yore’s installation: Max Delaney, Senior Curator (Contemporary Art) at the National Gallery of Victoria; Jason Smith, then Director and CEO of Heide Museum of Modern Art (and now Curatorial Manager of Australian Art at the Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art); and Antonia Syme, Director of the Australian Tapestry Workshop. Collectively, the witnesses had over sixty years of experience as curators, conservators and directors in the Australian arts sector.

The evidence of the expert witnesses gave important context to the installation as a whole, and the excised photographic images. Each expert referred to the significant professional recognition and critical acclaim Paul Yore had received to date. The witnesses commented on Yore’s techniques and methodologies and the subject matter his work explored. Each expressed the view that his work generally, and the Everything is Fucked 2013 installation specifically, possessed significant artistic merit.

Antonia Syme described the work as ‘challenging, amusing, kitsch, provocative (as good art should be) and clever’. Jason Smith considered it a ‘tour de force’ which ‘deliberately played with and subverted styles, and had a healthy disregard for cultural difference in order to focus attention on the bewildering, disquieting scope and density of our wildly consumer-based lives’.

Max Delany emphasised that contemporary art is not always about pretty pictures. In his opinion, contemporary art was a place for difficult, sometimes confronting, subject matter, because artists provide us with images and ideas that are often important alternatives to mainstream representations of culture.

While the Prosecution tested the evidence of each of these witnesses in cross-examination, it did not call any expert evidence to rebut the artistic merit of the work.

Decision

On 1 October 2014, Magistrate Amanda Chambers dismissed each of the charges and ordered Victoria Police to pay Paul Yore’s legal costs. In reaching her decision, the Magistrate found that one of the seven images constituted child pornography, but that the classification defence operated in respect of that image.

Given these findings, the Magistrate did not find it necessary to consider the artistic merit defence. The absence of any commentary or observations on this defence was somewhat surprising, given that evidence in support of this defence had occupied the bulk of the hearing time and the Magistrate had engaged with the expert witnesses on this issue.

However, it is noteworthy that the question her Honour posed (but did not answer) in her written reasons, was whether the Prosecution could establish beyond reasonable doubt that the defence of artistic merit could be ‘excluded’ confirming that

once an accused person advances an evidentiary foundation for the defence of artistic merit, the onus is on the Prosecution to prove beyond reasonable doubt that the work in question does not possess artistic merit.

Role of the right to freedom of expression

In considering whether each of the seven images constituted child pornography, Magistrate Chambers accepted the Defence submission that the statutory definition of child pornography should be interpreted consistently with the common law right to freedom of expression, and the statutory right to freedom to impart information and ideas of all kinds, including by way of art, contained in s 15(2) of Victoria’s Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006.[iii]

The Magistrate observed that Paul Yore was entitled to these rights, even where the imagery he used would be confronting or offensive to some members of the public. She described the installation as confronting, and intentionally so. The Magistrate adopted the Supreme Court of Canada’s expansive interpretation of the right of freedom of expression in the Canadian Charter of Human Rights, as protecting not only ‘good’ and popular expression, but also unpopular and even offensive expression.[iv]

However, Magistrate Chambers also observed that the right to freedom of expression, both under the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and at common law, was not absolute. She referred to section 15(3) of the Charter, which provides that ‘[s]pecial duties and responsibilities are attached to the right of freedom of expression and may be subject to lawful restrictions reasonably necessary – (a) to respect the rights and reputations of persons; or (b) for the protection of national security, public order, public health or public morality’.[v]

In the Magistrate’s view, by criminalising the production and possession of child pornography, Parliament was giving effect to society’s interest in protecting children from the evils associated with the possession of child pornography. These included the harmful exploitation of children involved in the production of child pornography. The Defence submitted that it was clear no children had been exploited in the creation of the images in question, as photographs of children’s faces had been affixed to photographs of naked adult bodies. However, the Magistrate observed that child pornography (whether or not children were involved in its production) had the capacity to harm children in different ways, as its dissemination and use facilitated the seduction and grooming of children; might break down inhibitions about the sexual abuse of children; and could be used to incite potential offences.[vi]

Collage as a ‘photograph’ or ‘publication’ constituting child pornography

Each of the seven images was constructed as a collage, and obviously so. Jason Smith gave evidence that in the seven images, ‘the figures are obviously collaged from a number of sources’. Max Delany described the collaged images as ‘metaphoric, allegorical, rhetorical and hyperbolic, [operating] in the realm of the surreal or fantastical, rather than in relation to reality’ and described the installation as incorporating elements of collage in ’deliberately artificial and un-naturalistic ways’.

The Magistrate concluded that the seven images had been created in a ‘clearly artificial way’, and that it would be ‘apparent to any reasonable observer that the image depicted is not, in truth, a child, but an adult juxtaposed with a child’s face’. She accepted the Defence submission that the images were to be viewed in the context of the work as a whole. In relation to six of the images, she said that she was ‘not satisfied the provisions of the Act were intended to cover such artificial constructs in an artwork’, given the purposes and objectives of Parliament in criminalising the production and possession of child pornography.

However, notwithstanding the artistic context and the artificial nature of the construction, the Magistrate held that one of the seven images constituted child pornography. The one offending image was described as a ‘close-up image of a male child’s face, appearing to the reasonable observer to be performing fellatio on an adult penis’. The Magistrate did not elaborate on why this collaged image fell within the definition of child pornography, while the other six (another of which also depicted an act of fellatio) did not.

Having found this image to constitute child pornography, the Magistrate went on to find that the image had been ‘possessed’ and ‘produced’ by Paul Yore. The Magistrate rejected the Defence submission that the act of sticking together two photographs to create an image was not an act of ‘printing or otherwise making or producing child pornography’ (as section 68 of the Crimes Act required), particularly when that provision was interpreted having regard to the maximum penalty imposed on the offence. The Magistrate said she found no basis to give the words of section 68 anything other than their ordinary meaning, particularly when regard was given to the protective purpose of the provision.

Classification of a photograph or publication by the Australian Classification Board

Visual and performing artists are obviously under no obligation to have their works classified (in contrast, for example, to producers of films, computer games and television broadcasts).

The Everything is Fucked 2013 installation was not classified before the exhibition opened at Linden. However, in the week following the execution of the search warrant, having closed the exhibition, the Board of Linden applied for a classification from the Australian Classification Board. The Board of Linden submitted for classification a series of photographs of the installation (taken before the execution of the search warrant), which included a photograph of the image found by the Magistrate to constitute child pornography.

In a written decision, the Australian Classification Board gave a Category 1 Restricted classification (ie unsuitable for a minor to see or read). As this was not a classification of RC,[vii] X or X18+, the classification defence operated.

Magistrate Chambers referred to the Classification Board’s written decision, and noted in particular that the Classification Board had made specific reference to the image which she considered constituted child pornography. The Classification Board’s reasons recorded that a minority of the Board was of the opinion that this image ‘depicts in a way that is likely to cause offence to a reasonable adult, a person who is, or appears to be a child under 18 and therefore deal with matters of sex in such a way that it offends against the standards of morality, decency and propriety and should not be classified’. However, this view was not embraced by the majority of the Board, which gave a Category 1 restricted classification.

The Magistrate concluded that as ‘the prosecution is unable to point to any cogent or contradictory evidence upon which it can establish beyond reasonable doubt that the image would [if classified in May 2013] have been classified other than Category 1 restricted’, Paul Yore had a defence to the charges of producing and possessing the image that constituted child pornography.

The police excision of images from the installation

Although there is no mention of it in her written reasons, Magistrate Chambers made comments at the time of publishing her written reasons about the conduct of the police in excising the images in question from Paul Yore’s installation. Her Honour expressed concern about the use by the police of a Stanley knife to excise these images, and questioned whether on a proper analysis of the search warrant (which had not been tendered in evidence), the police had been authorised to take such action.

A search warrant generally authorises the seizure of things found at the premises in the course of the search that the officer reasonably believes to be evidence in relation to the offence the subject of the warrant. While the legality of the manner in which the search warrant was executed was not an issue pressed by the Defence, there remain real questions as to whether a standard form search warrant would give the police power to cut pieces out of a work of art, particularly where:

- in Jason Smith’s opinion, ‘[t]he excision of the seven collages destroyed Paul’s work – simple’;

- Paul Yore had a right not to have his work subjected to derogatory treatment (being any act that results in a material distortion of, mutilation of or material alteration to the work that is prejudicial to his honour or reputation);[viii] and

- six of the seven excised images were ultimately found not to constitute child pornography.

Conclusions

As a first instance decision of the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria, the decision in Paul Yore’s case is of limited precedential value. However, given that the Magistrates’ Court of Victoria regarded an image from a publicly exhibited work of art as constituting child pornography, artists should continue to exercise caution before exhibiting works that are capable of being viewed as depicting children in a sexual context or engaged in sexual activity (even where the work has a limited target audience or is clearly surreal or fantastical).

The Magistrate’s acceptance of the classification defence in relation to an image from an art installation is encouraging, and artists may wish to consider seeking such a classification before exhibiting works of such a nature.

Artists should also be encouraged by the Magistrate’s acceptance that the right of freedom of expression is relevant to the interpretation of statutory definitions underpinning criminal offences such as those involving child pornography, as well as the Magistrate’s observations about the potential limitations on the authority of police to cut into a work of art pursuant to a search warrant.

This article was first published in Issue 1 2015 of the Arts Law Centre of Australia’s art+LAW newsletter.

[i] Johnson v Yore (unreported, Magistrates Court of Victoria Case No D12709566, 1 October 2014).

[ii] Helen Hughes, “Like Mike – Reviews” in Frieze no 157 (September 2013).

[iii] Section 32(1) of the Victorian Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 provides that ‘[s]o far as is it possible to do so consistently with their purpose, all statutory provisions must be interpreted in a way that is compatible with human rights’.

[iv] See R v Sharpe (2001) 194 DLR (4th) 1 at [21].

[v] The Magistrate also referred to section 7 of the Charter, which provides that a human right may be subject under law to such reasonable limits as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society, having regard to a range of factors, including the importance of the purpose of the limitation and the nature and extent of the limitation.

[vi] See R v Quick [2004] VSC 270, a decision of the Supreme Court of Victoria.

[vii] Interestingly, the National Classification Code, which the Classification Board applies, provides that publications that depict children in a manner likely to cause offence ‘to a reasonable adult’ are to be classified RC, whether or not the person is engaged in sexual activity.

[viii] Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), sections 195AI(2) and 195AK.