Tino Sehgal’s Kiss purchased by MoMA.

While performance art has been around since the 1960s, we are riding a wave of an extraordinary resurgence in its popularity right now, which has precipitated the need for new definitions, especially when it come to collecting and buying live art.

Performance has increasingly become part of our mainstream, shown at biennials and art fairs around the world, and with leading museums such as Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Tate Modern, and Centre Georges Pompidou creating departments devoted to performance art, this is no longer the practice of the peripheral.

Take as a quick historical marker four recent cases: MoMA’s purchase of Tino Seghal’s Kiss in 2008 for $US70,000; Brisbane’s Gallery of Modern Art’s (QAGOMA) recent exhibition Trace: Performance and its Documents, drawn from its collection; Artbank’s program of commissoning performance-based artworks; and the Kaldor Public Art Project’s presentation of its recently acquired work by Tino Sehgal, This Is So Contemporary, shown at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW) last month.

Before we examine these in more detail, let’s return to the basics. What are we talking about when we say “performance art” in a contemporary context?

By definition, performance art is ephemeral, often spontaneous or interactive, but always based around the notion of an experience. Unlike a painting or sculpture it is not a tangible object. So then, how it is collected, documented or owned?

Performance art by definition sits at odds with established systems for institutional material management. The residual of that – film, video, photography, props, ephemera – stand in for the original action. But does this record have the same “value” as the live performance?

MoMA set up its first Media and Performance Department in 2008 under Chief Curator Klaus Biesenbach and employed a conservator of performance art, Glenn Wharton. It was part of a broader shift in mindset and coincided with the launch of a two-year series of live pieces, both new and re-created, that culminated in the 2010 retrospective of Marina Abramović, titled The Artist Is Present (2010). Across town, the Guggenheim Museum presented a one-man show of Tino Sehgal’s work, P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in Queens was showing 100 Years, and the Neuberger Museum presented Tania Bruguera. A new renaissance was born!

In the midst of this activity questions were being raised: Is the presentation of these performed artworks authentic to the original live act, afterall this is a question of collecting, not exhibiting.

At the time MoMA’s director, Glenn Lowry said, ‘There are no precedents here.’ Klaus Biesenbach, co-curator of 13 Rooms, which came to Sydney 2013 as a Kaldor Public Art Project, and curator of both the Marina Abramović (2010) and Pipilotti Rist (2008) shows at MoMA – and said to be ‘the man charged with acquiring this kind of art’ – commented at the time to New York Art about the hot topic of how to collect performance art: ‘The sessions go on forever – like, hours…They addressed everything from the discrepancies between a performance and its remnants to legal quirks to the appropriateness of an institution’s owning work created to subvert institutions.’

At the same time as these discussions MoMA purchased Kiss, a durational performance by Tino Sehgal. Sehgal does not allow his work to be photographed; there are no wall labels or catalogues, no official openings or press kits. It is a something we experience on a more local level this year with the presentation of his work, This is so contemporary, owned by Kaldor.

MoMA is reported to have paid $US70,000 for Kiss, and with no written contract, just the transference of the artwork to a curator orally (unrecorded), who then is charged with the role of ‘interpreter’. The work is an edition of four; two other museums have bought it so far. And it can be lent, like a painting.

‘The market is something you can’t be outside of,’ Sehgal told an audience at MoMA(May 2009).

‘If the work gets resold, it has to be done in the same way it was acquired originally,’ Jan Mot, Sehgal’s Brussels dealer, told The New York Times.

That period between 2008-2010 was a heady time of change, and with MoMA’s new acquisition policy in place, it went about collecting works and setting a new global benchmark for doing so – the right of which was to re-perform what they now owned. Key among them were:

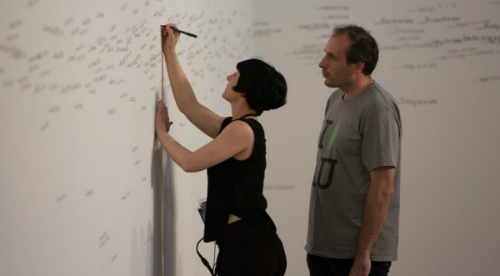

Roman Ondak Measuring the Universe (Acquired by MOMA in 2007). You may remember this work, which Kaldor Public Art Projects presented at Parramatta’s historic Town Hall as part of the Sydney Festival in January.

Allora and Calzadilla Stop, Repair, Prepare: Variations on Ode to Joy for a Prepared Piano (Acquired by MOMA in 2008).

Michelangelo Pistoletto Seventeen Less One (Acquired by MOMA in 2008).

The question then may not be “Can performance art be collected?” but rather “How are we collecting live art?”

With this growing debate globally, the Tate in London conducted a two-year research project to updates up MoMA’s developments (April 2012-January 2014). Bringing together Dutch and British academic scholars and museum professionals its aim was to gain greater insight into the conceptual and practical challenges related to collecting and conserving artists’ performance.

The results are yet to be published but a series of keynote lectures have been shared online.

Sabine Breitwieser, Chief Curator, Department of Media and Performance Art, MoMA, said: ‘Performance art takes on various formats after its first “live” formation and can be considered as hyper-media. Artists have spent a great deal of time and experience to think about how their artwork can be represented after it was performed.’

She added, ‘Like the presentation of any complex and relational work, the presentation and mediation of performance art requires in depth research and a certain choreography to be discussed and developed. In fact the politics of representation of process and time-based oriented artworks plays a significant role in 20th century art until today.’

It was a pathway MoMA conservator Glenn Wharton also advocated, making the point that their acquisitions were works ‘originally designed for museum spaces, so were well suited to a museum collection and for subsequent curation’.

Whaton’s comments were part of panel discussion that can be found online at ArtOnAir.org, organised by Roselee Goodberg, founder of the performance art biennial PERFORMA, with the theme: ‘It’s History Now: Performance Art and the Museum’.

Wharton said that their team of curators and conservators conduct artist interviews with all works acquired to discuss details of how the artist work is to be re-performed.

This brings us back home to Brisbane. QAGOMA tackled the topic from an Australian perspective with their exhibition Trace: Performance and its Documents (22 February – 27 July 2014).

Curator of Trace Bree Richards said, ‘This interest in performative forms of art is being driven by a number of overarching factors: the abundance of new technologies has had a huge impact on the reception of performance, as it is now easier than ever to document and distribute; a growing trend towards self-surveillance and public sharing via online platforms and social networking; and the rise of mass media and a celebrity-obsessed culture. We live in a time that is essentially awash with “performance”.’

Another example, and one relatively unique across my findings, is Artbank’s Performutations series curated by Daniel Mudie Cunningham. The art leasing company has committed to commissinig six performance artists to create works specifically for their collection.

Tony Stephens, Director of Artbank told ArtsHub: ‘They are artists we wouldn’t necessarily have been able to collect so we thought if we were going to commission them, why don’t we give them a life beyond traditional media and launch them online’.

Justene Williams is the most recent to join the Performutations alumni including artists: The Kingpins, Heath Franco, Mark Shorter, Liam O’Brien, and Laresa Kosloff. Clearly, such initiatives add to a collective swell that performance art can live beyond the moment.

There will always remain divergent views on this topic. Hector Canonge, Artist and Founder of the Itinerant Performance Art Festival (New York, NY) reflects a commonly held counter view. He said: ‘Unlike theater, dance and other performative disciplines, performance art exists for a particular moment within a particular historical, social and political framework. The relevance of a piece might be extremely important in a determined period of time, but within a few years, that relevance might not speak to audiences in the same manner. Therefore, although the performance might be the same, its message might not translate or be what the artist intended.’

There is foundation in Canonge’s argument, however, when one looks at projects like 13 Rooms where historical live artworks are presented alongside newly commissioned pieces, surely that framework of presentation and context ensures the relevance of these works is held in tact, across time. You be the judge.