While “burnout” may seem like a relatively new buzzword, a 2022 article in The Washington Post outlines the decades-long history of the term. In it, the author Jonathon Malesic describes how “burnout” was coined by a US psychoanalyst working in a free medical clinic servicing mainly young people, in the wake of a broken countercultural idealism. At the same time that the passionate and dedicated staff in the clinic were adopting the word to describe a growing phenomenon among them, it was becoming clear an imagined life that decentered work had made little dent in the intractable issues of capitalism.

By the 1980s burnout had become a key term to describe the widespread condition of frazzled and defeated US workers. Burnout was cited as the first reason the air traffic controllers union went on strike for better conditions and pay in 1981. According to Malesic, the then President Ronald Reagan’s response of firing all 11,000 workers taking part ‘sent a message that workers still hear today: they will deal with burnout on their own, or not at all’.

In contrast, contemporary conceptions of burnout tend to view it as an issue of mental health. In my creative Millennial circles with high mental health literacy, discussions of burnout have become so ubiquitous that being somewhere on its spectrum is entirely unexceptional (as is the experience of its close associates, anxiety and depression). As too many of us are finding out, work-related burnout is a strong contributor to “allostatic load”, a term that describes the cumulative burden of chronic stress on individual health, and which is associated with an alarming range of physical and psychological impacts.

Concurrently, there has also been a proliferation of books and articles offering advice for burnout prevention (my local bookstore stocks no less than four different publications). These texts typically advocate for self-care in the form of self-mandated rest, meditation, “completing” your stress cycle or seeking psychological support. They also advocate that we maintain stronger boundaries, engage in “quiet-quitting” and adjust our expectations around productivity. However, these conceptions continue to put the responsibility on individuals. We are still dealing with burnout on our own, or not at all. All the while, these framings disguise the root cause: a socioeconomic environment that treats its primary producer as a resource for maximum extraction.

Read: Are ‘quiet firing’ and ‘quiet quitting’ real in the arts?

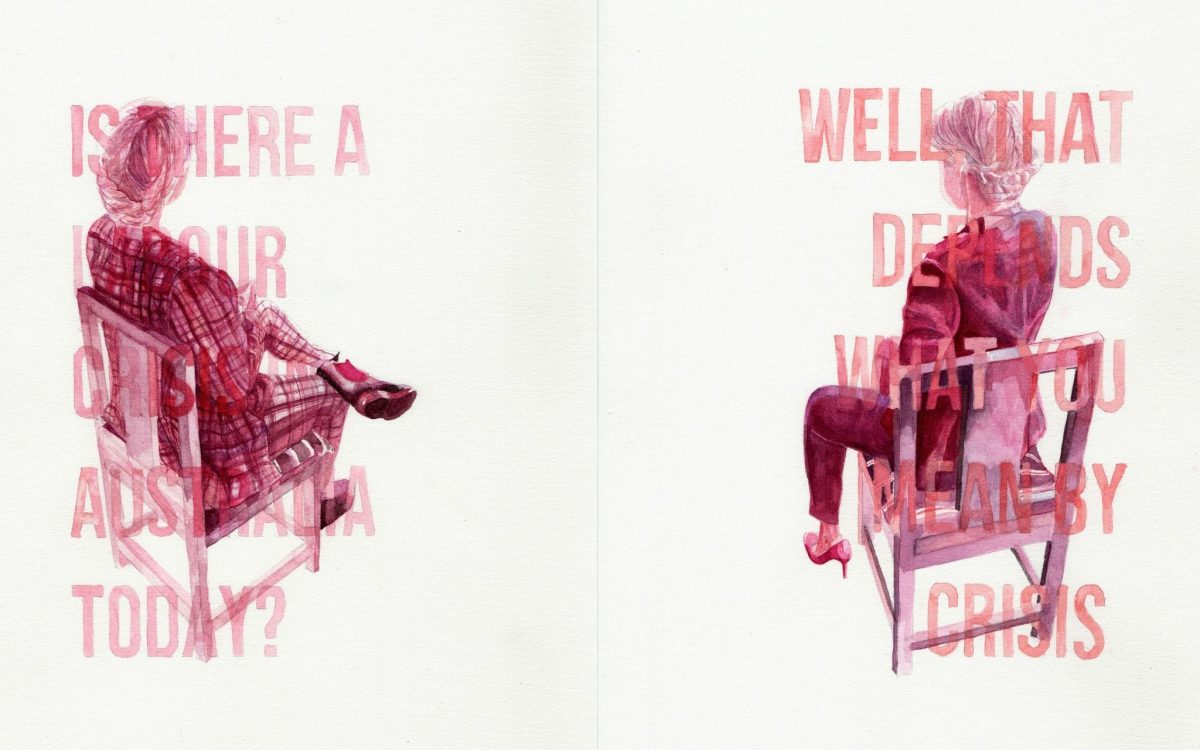

Artist burnout

While it is reported that, since the pandemic, Australian workers are in poorer physical and mental health across all ages and stages, I believe that the artist burnout in the contemporary socioeconomic context has a particular dimension to it. Much of this has to do with the fact that artist work is largely immaterial, which makes it hard to quantify and set boundaries around. As with many vocations, artists do not “clock off” at 5pm, but are implicitly labouring as we go about our lives. Artists labour not just with our bodies, but with our subjectivities, our communicative abilities, our identities, our cultures and our communities. These are inherently human kinds of labour that blend work and life to a great extent by involving our whole selves. In doing so, we can become “human capital”.

These elements of artist labour are not generally valued by ideologies of budget-balancing austerity. However, they are actually incredibly valuable in an economy that no longer relies on the production of physical commodities as its primary mode of producing value. As media philosopher Franco “Bifo” Berardi points out, our economy now predominantly creates value by mobilising attention, which is driven by workers’ creative, affective and communicative abilities. The artistic activity of creating new aesthetic trends, stimulating cultural engagement and producing new discourses is readily absorbed into a flow of immaterial commodities. The structures that channel them create wealth for property developers, media platforms and other corporate entities, but this is rarely seen by artists themselves, and far exceeds any financial investment made in them.

The attention economy has also increasingly defined the terms by which we commission contemporary art. The development of temporary employment, funding and presentation models pressurised by attention-based KPIs of visibility, speed, volume and mass engagement drives the perpetual mandate of “new, now”. This incentivises a constant, often panicked, flow of disposable artistic activity – a constant, often panicked, flow of disposable artists.

In this production paradigm where artists are generally independent gig-workers, our creative communities are also easily instrumentalised as “professional networks” for the purposes of production. As the attention economy leaks into our relationships, too many of us experience the pressure to remain socially visible as well as creatively visible, for fear that we may be forgotten by the constant flow. In such contexts, one’s economic survival means engaging in deep, affective kinds of labour. We must present unceasingly as capable, professional, autonomous, available, personable and engaged as we individually compete for limited opportunities.

This social effort is compounded for those who are not a member of the racial or cultural default, those who have a social or physical disability, or those carrying relational trauma. It is no surprise that support seeking is implicitly disincentivised in this environment. As journalist Malcolm Harris has described in his book on how Millennials became human capital, when your work essentially depends on your likeability, depression and anxiety aren’t just threats to our psychic well-being but become seen as ‘an error that must be corrected’.

While the ability to adapt to the paradigm is generally valourised as passionate, entrepreneurial aptitude, I believe it is better interpreted as a survival adaptation. Artists, who currently have little control over the structures that produce art, have not much choice but to shape ourselves to the precarities that trickle down through the industry while taking on the burden of managing our own internal condition. Too often, we blame ourselves when burnout removes our option to continue. However, when our industry extracts its value from deeply human places, offers little in terms of stability or remuneration and erodes community support, burnout is simply an inevitability.

Shifting our advocacy

Berardi notes that our psychological and economic processes naturally interweave. As the economy gains speed and the labour force is rendered temporary, we feel overwhelmed, inducing a panic that concludes with a depressive plunge. Rather than such experiences being a mental health issue, he frames it differently as ‘the soul on strike’. Part of yourself has no choice but to stubbornly withdraw its participation amid unsustainable conditions.

This reframing of burnout in labour terms would implicitly shift our industry advocacy around artist well-being. If this lens meaningfully took hold, we would cease to be content with responsibilising supports, such as mindfulness resources or articles on self-care. We would also cease to advocate for superficial adjustments, or simply “more funding” within the same exploitative format. Instead, we would recognise that the industry needs to be fundamentally reorganised as an issue of urgency.

Recognising that we deserve far better could be the impetus to create a stronger collective voice. In tandem with a shifted consciousness that values the full spectrum of labour we engage in as artists, the possibilities for changing to a more artist-centred industry model grow. In doing so, commissioning and funding structures that sustain practices that are long-form and iterative may become the standard. Our funding bodies may adopt accessible and generous processes that fundamentally support artists, rather than gatekeep funds from them using arduous application processes, and attention-based indicators of worthiness.

It could be mandated that all arts institutions employ local artists on salary and have them contribute to organisational decision-making as has been piloted by HOTA (Home Of The Arts) (Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia). Property developers, media platforms and other corporate entities who profit from the activity of artists may be appropriately taxed and that wealth more equitably distributed, perhaps in the form of a basic income for artists as is being trialled in Ireland.

Rather than operating as individuals, we may have a strong artist union complementing a collective culture among artists, and we may go on strike together before our souls leave us no choice.

This article is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.