With the recent escalation of censorship cases in Australia citing child pornography, one might raise the question whether we are isolated in this hyper sensitive, and often reactionary trend.

The answer, sadly, is no. Last Wednesday, 9 October, British artist Graham Ovenden was sentenced to 27 months in jail after the Court of Appeals in London overturned a previous sentence of 12 months as too ‘lenient.’

Following Ovenden’s conviction, the Tate Gallery removed more 34 Ovenden prints from its online collection and prints from its reading room until its Board had made a review.

Attorney General Dominic Grieve referred the case for appeal. Grieve tweeted on Wednesday’s outcome: ‘Ovenden committed terrible sexual offences against vulnerable girls and abused his position of trust.’

Grieve added, ‘Sexual crimes whether committed years ago or recently should be punished appropriately. Today the court sent a clear message.’

The 70-year old artist, whose work is held in collections internationally including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, was convicted in June of six charges of indecency and one of indecent assault dating back to the 1970s and 80s – the target of his actions young girls who posed for his photographs.

It has echoes of another high profile British case, namely Australian entertainer Rolf Harris, whose trial date was announced by Westminister Magistrate’s Court just two days prior to Ovenden’s verdict. (30 April 2014)

Harris, 83, has been charged with nine charges of indecent assault involving two complainants dating back to the 1980s, and four charges of making indecent images of children relating to alleged incidents last year.

Is there sudden clarity for past actions, or has a change in laws precipitated their justification? How much did the Jimmy Savile case in the UK ratchet up what Ovenden has called a ‘global witch-hunt against artists.’ Reported BBC news.

Ovenden’s images of children have triggered several legal actions over the years, the blog Pigtales in Paint has tracked that trajectory in an attempt to balance the facts, from 1991 when proofs of his photographic book States of Grace were seized by US Customs, to a 1993 police raid by the Obscene Publications Squad of Ovenden’s UK home seizing his archive and announcing they had “smashed” an extensive pedophile ring, to 2009 with a charge of sixteen counts of creating and two counts of possessing “indecent” photographs or pseudo-photographs of children.

None of these charges couldn’t stand up in court. This time, however, they have.

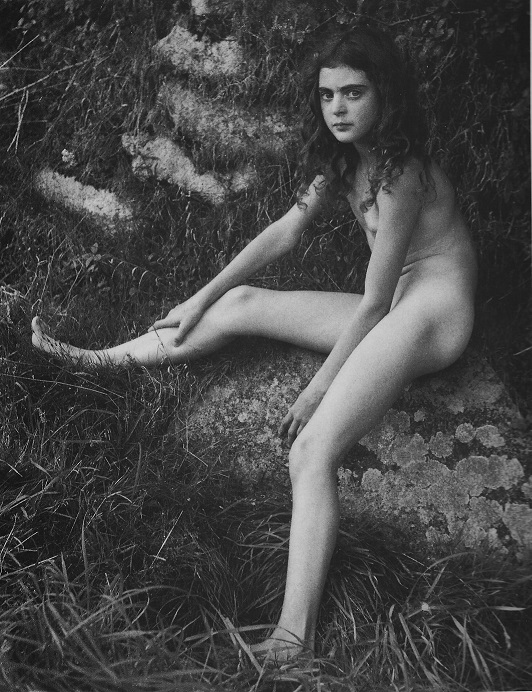

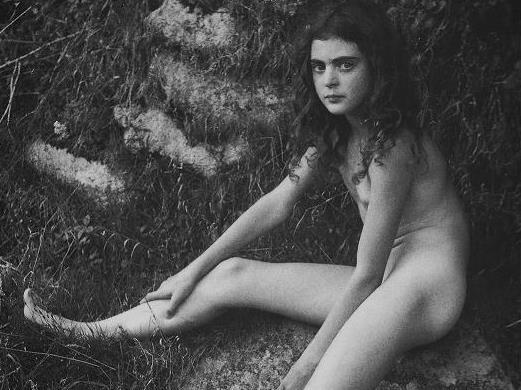

From Ovenden’s series States of Grace 1973. Source pigtailsinpaint.com

The court rejected Ovenden’s claim that his interest in young girls was artistic and not sexual. Lord Chief Justice Lord Thomas heard the Appeal case. He commented to the BBC, ‘He [Ovenden] seeks to blame others and asserts a conspiracy against him…He still asserts that art is being put on trial. That is nonsensical bearing in mind the facts.’

When any artist chooses subject matter involving the images of naked or semi-naked children, the conventional wisdom has become that there must be some sinister intent.

The Independent reported that the 34 images removed from Tate, were gifts received in 1975 ‘as part of a larger gift of around 3,000 works and include images of naked young girls’.

A spokeswoman for the Tate says: ‘While this review takes place, the works by Graham Ovenden held in the national collection are not available to view online or by appointment. The change in sentence does not affect this review.’

Pigtales added, ‘In the event that any images are legally deemed indecent by the courts, the Tate may be forced to destroy the work, as it is no more legal to possess than to display “obscene” material, nor could they be legally sold or donated.’

It must be noted that the works held in the Tate Collection were not the subject of the recent trial. It would be tragic if this archive of work is lost as a mere symptom of a more pressing problem.

_Encounters-in-Reflection_Gallery3BPhoto-by-Anpis-Wang-e1745414770771.jpg?w=280)