It was an ordinary lecture to first-year students, on “Women Writers and Modernism.” My brief was to introduce the different ways men and women responded to the social, intellectual and artistic challenges of the modernist movement.

This is a subject about the literature of the early 20th century, but it tackles some difficult social questions too. While men were facing the horrors of war, the challenges of industrialisation and the disruption of many familiar intellectual and social hierarchies, women were gaining access to education, greater participation in the democratic process, and fuller employment.

I told the students that several days ago on talkback radio, where the topic was sexual and domestic violence against women, I had heard a caller say that many men felt threatened by women’s increasing participation in the workforce. These were complicated issues, I said, but it did seem that we were still rehearsing arguments that were current over a hundred years ago, and that these patterns of anxiety were part of broader systemic patterns associated with patriarchy and capitalism.

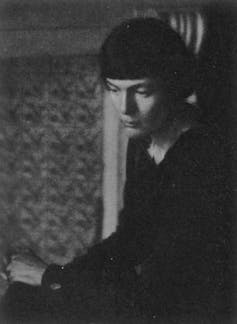

A 1917 portrait of Hilda Doolittle. Wikimedia Commons

But it was time to turn to my women writers. I began with Hilda Doolittle (re-named “H.D.” by Ezra Pound), and talked about the way many women writers re-wrote classical stories from a woman’s perspective. I clicked on to my next slide, part of her poem written in 1916, Eurydice.

I stopped. Silence fell around me, and I could not speak. I tried again, but could not get out a word. I had been in full rhetorical flight in front of several hundred students, but suddenly felt an awful silence spreading, as my students realised first that something was wrong, and then as they realised why I had stopped.

The elegant and unusual name Eurydice — and the awful death through sexual violence of a young woman, less than a kilometre north of our campus, less than two months ago — was resonating powerfully in the lecture theatre.

Unable to speak, I felt a moment’s panic and shame, fearing the students would think I had staged the whole thing for dramatic effect. For surely I could not be surprised by my own choice of text.

I gathered myself together, reminded the students of the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice (abducted by Hades into the Underworld and released into Orpheus’ care on condition he not look back until he leads her into the sunlight), and read these lines.

So you have swept me back,

I who could have walked with the live souls

above the earth,

I who could have slept among the live flowers

at last;so for your arrogance

and your ruthlessness

I am swept back

where dead lichens drip

dead cinders upon moss of ash;

so for your arrogance

I am broken at last,

I who had lived unconscious,

who was almost forgot;if you had let me wait

I had grown from listlessness into peace,

if you had let me rest with the dead,

I had forgot you

and the past.

Eurydice Dixon. AAP

The students were still and silent as I read. Hearing this voice of a dead woman from the mythical past called up the presence — I think we all felt it — of the young woman whose story we all knew. For those few moments, we held vigil for Eurydice Dixon.

This is what it feels like to be “triggered” by literature, to have a fictional incident or even a name suddenly ambush you from your train of thought, your narrative curiosity, and your readerly pleasure. Literature can take your breath away, even when the trauma it recalls is a communal one, not a personal tragedy.

And yet I only half-heartedly, and only occasionally give “trigger warnings,” advising students that they may encounter violence and trauma of various kinds in literary texts. The best argument for such warnings is not that students can then refuse to read, but that students suffering post-traumatic stress may prepare themselves for the confronting business of discussing literary texts in classes: the emotional engagement with others in a public setting.

Titian’s Orpheus and Eurydice, painted circa 1508. Wikimedia Commons

Such warnings testify to the very real power of literary texts to challenge and confront us, often in ways we cannot anticipate.

But this incident also reveals the impossibility of such warnings. There was no way I could have known I would be taken so deeply by surprise at my own response; no way I would ever have warned students that a poem about a mythical abduction to the Underworld might trigger this awful feeling.

Literature works in mysterious and unpredictable ways. This episode reminds us of its astonishing capacity to strike emotional chords and resonances. Such moments can make us feel awful, and uncomfortable, and can disrupt our carefully managed public and professional performances of the self, but they can also generate strong emotional connections between people, across time and different cultures. Of course I can’t be sure what all the students were thinking, though an unusual number of them came up to me afterwards and thanked me for the lecture.

Moreover, if literature produces this sting, it also produces the cure. Seeing H.D.’s beautiful poem on my screen gave me the courage to go on, and to do justice to her work. The poem gave me the words to say next. Reading that poem — finding structure and pattern in its cadences; and finding a voice in its lyrical core — produced poetic order out of emotional chaos.

Stephanie Trigg, Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor of English Literature, University of Melbourne

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.