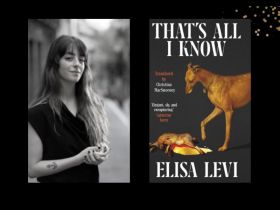

Image: Geraldine Kang, In the Raw

Lovers, friends and family have always been the favourite source of inspiration for artists. But there are always (at least) two sides to the story a writer, filmmaker or portraitist tells. Involuntary muses are not always happy to be turned into characters of a novel or to have their appearance reinterpreted by an artist friend – especially if the art deals with intimate, personal and potentially embarrassing themes.

There are plenty of famous cases of writers and artists who have sacrificed friendships and even family attachment to the altar of art – not to mention those who have hung old lovers out to dry.

Artist Joshua Smith sued William Dobell over Dobell’s 1943 Archibald Prize-winning portrait of Smith, his lawyer describing it as a ‘pictorial defamation of character’. Dobell won but the friendship between the two artists was destroyed by the portrait.

Carl Bernstein (of Watergate fame) threatened to sue his former wife Nora Ephron over her novel and later film Heartburn, which recounted his affair. Ephron was just learning from example. Her parents made her college letters home into a play and film Take Her, She’s Mine.

Writers are always told to write what they know but how does one use real people without exploiting them? This question – always a challenge for writers – is all the more striking with the growth of mash-up genres such as fictionalised memoir and image manipulation.

Risking the hurt

‘Writers should be bold,’ says novelist and playwright Michele Lee. ‘They shouldn’t be sociopaths but they should be bold.’ In her memoir Banana Girl, Lee uses her turbulent relationships with lovers, friends and family members, preferring begging to seeking permission.

She knows she runs the risk of hurting someone’s feelings but is not prepared to allow that danger to limit her writing. ‘If your main objective in writing about your life is to defer to the imagined feelings of others, then you’re probably going to end up in a constrained mindset, and hit a lot of walls in writing.’

Only when a first draft is laid out, Lee makes decisions about what to keep in, and how to reconstruct moments. In this phase she asked some of the major people chronicled to read ‘their bit’. ’One of the currencies you’re working with in memoir is real people. So of course at times they’re all you can think about when you’re re-writing and editing.’

An early reader of Banana Girl, Lee’s sister Mary, was shocked reading her character but was forced to admit the portrayal was accurate. ‘My sister had pretty much summed up who I was as a person at the time that the book was written. After I got over the shock, I was fine with it,’ she told ArtsHub.

The Lee sisters were able to survive the unflattering portrayal in part because Mary understood that the book represented her sister’s perspective not her own truth. ‘I did not feel the need to ask for control over the way Michele was writing me. Reading Banana Girl didn’t affect my relationship with my sister at all,’ she said.

Lee’s attitude was different in writing about the people she had less of a relationship with. ‘In that case I didn’t spend as much time thinking ‘What will they think if they read this?’ because I suspected they wouldn’t hear about it or be going out and buying it.’

She also points out that a memoir is not about finding an objective truth but about memory, perception and personal meaning. ‘It’s my version of the truth. And of course the dialogue is not verbatim. And maybe a dress was cobalt blue not emerald green.’

An exercise in acceptance

Photographic portraits presents the same kind of challenges as memoir. While they cannot be made without the co-operation of the subject, the reality of what you can do with light and lenses – not to mention Photoshop – means artists create rather than record the image of the another person.

Singaporean artist Geraldine Kang said the artist is in a position to manipulate an image. ‘A photographic portrait is always an exchange between two identities and usually it is more about the photographer than the person being photographed. You are the one controlling the lens, you are the one telling them how to pose. You are the one trying to elicit reactions or expressions.’

Kang has made many photographic series using friends and family. In the awarded series In the Raw she depicted her family members in surreal situations dealing with nudity, aging and death. She said In the Raw was a ‘shock treatment’ to introduce her parents to her art practice, which in the beginning they didn’t understand.

Image: Geraldine Kang, In the Raw

Kang said art is a way to process her thoughts and feelings and to get herself ‘out of her head’. For In the Raw, she was inspired by photographers Tierney Gearon and Sally Mann. ‘They use the naked body in a way that is quite natural. It’s not normal for people to bare their bodies in public, and nudity in proximity of the family is particularly uncomfortable. There are so many layers of meaning put upon the naked body. I was really fascinated by that and with In The Raw I transplanted this idea into my own family.’

Nudity is a taboo in Kang’s family and their surrounding Singapore culture, but that didn’t discouraged the artist. ‘A lot of people ask me how I got my family to take off their clothes. And they are surprised when I told them it didn’t take that much. I just told them: can you do this? They would be a bit uncomfortable but they would do it anyway.’

The artist now looks at In the Raw as an exercise of acceptance on both sides: ‘I see the work as a sort of compromise between me and my family. I show them what I am dealing with as an artist and see how far are they were willing to go with me.’

Geraldine’s father, said that when her daughter asked the family to take part in the series, he had no idea what she was doing. He only knew it was her school project. ‘I didn’t probe further as we did not want to add more stress to an already stressful situation. As parents, we try our best to help her in whatever way we can.’

Kang senior explains that, being brought up in a conservative family, at first he was taken aback hearing about his daughter’s project. ‘[She] took a while to convince myself and my wife it’s all about art and to just place our trust in her.’ At the same time they didn’t set any boundaries at all to Geraldine’s creative process. ‘I was fine as long as she didn’t make us a laughing stock through her pictures.’

Maintaining empathy

In The Raw gained great success and was repeatedly exhibited in art galleries. This accomplishment, together with Kang’s stubborn commitment to her craft, enabled her parents to understand her seriousness about art.

‘Support really did change. They still don’t know what I’m doing, but they come to my shows. Sometimes they bring people to the exhibitions and they even help me with my work, my dad especially,’ she said.’

Michelle Lee hsaid understanding the memoir process and keeping an eye on what you are trying to achieve ensures a writer stays on track and is not distracted by the personal challenges of working with material close to them.

‘Read the work of others, hear memoirists speak about their work, find mentors, find trusted people to give feedback on your work. Sometimes before I sit down to write a play I write a concept document or a slightly longer manifesto.’ This might be a useful exercise before plunging into the creative side of things. ‘You can return to it throughout your journey. It’s always really rejuvenating to go back to what you originally said your intentions for writing a particular piece was.’

In the delicate balance between creative freedom and respect for others, both Lee and Kang let empathy be their guide. ‘It’s about coming in and out of empathy pit stops,’ said Lee. ‘It can’t always be in the foreground, but it should be a place you stop in at.’