In the last year, our industry experienced a crash course in living at the mercy of disease. We’ve all learnt a lot about resilience, adaptability and living life without planning too far ahead: making, cancelling and re-imagining art at the whims of illness. These are all things that many of our colleagues with chronic health conditions and disabilities have known for years.

Now, as the COVID-19 vaccine enters the arms of Australians for the first time, this is the moment to reflect on what we have learnt and what we still have to learn. If non-disabled artists listen to those with chronic illness and disabilities, we may yet re-build as a kinder, more robust arts industry that is ready for anything and anyone.

As storyteller and performer, Yasemin Sabuncu says, ‘People might think we are a burden but [consider] our knowledge base and the skills we’ve learnt through overcoming. We are assets! A lot of people don’t understand just what we can contribute to a production or company.’

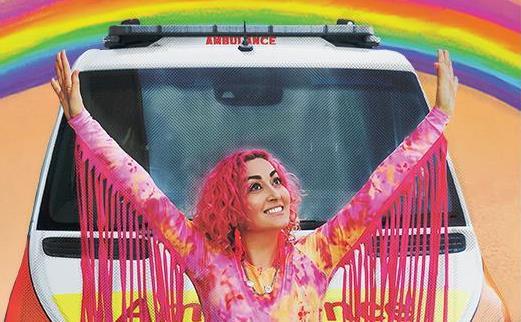

Sabuncu’s newest work, The illest at Adelaide Fringe, celebrates this fact, documenting her long journey with doctors, specialists and shamans and celebrating the determination it takes to navigate this journey.

‘We’re all survivors. We’re all legends.’

– Yasemin Sabuncu

‘We are assets! A lot of people don’t understand just what we can contribute to a production or company.’

Discussing the past year with disabled artists I get the sense that they have been here before. There is a certain “Yep, welcome to my life” vibe that pervades our conversations.

As Jamila Main says of the last 12 months, ‘It was so frustrating to watch all these non-disabled people/theatre companies struggle to adapt to COVID when I and so many of my disabled colleagues had ideas we have already tried and tested and worked with. We have the skills and ways of working already if they would just listen.’ Non-disabled folks are just playing catch up.

Read: Technology means disability is no longer invisible, but it’s not enough

One thing many disabled people reckon with is the sensation of lost time. Last year I frequently had the feeling that I was in a holding pattern, waiting for things to get back to normal so that I could get on with life. I had to remind myself that this was, in fact, living. Sabuncu knows this feeling well. Rather than waiting for things to get better, she regularly asks herself, ‘What if this is as good as it gets and can I be okay with that?’

Similarly, Main speaks of waking up on ‘good days’ with a sense of urgency and working non-stop to make use of the moment. As many of us have learnt in this last year, it can be hard to trust that the window of opportunity will stay open long enough for you to clean your teeth or make lunch when your lived experience has taught you to predict unpredictability.

Just as artists and venues must now learn to hold plans lightly and create work that can adjust for audience capacity, new health guidelines or sudden shifts to online, Main has learnt to be ready for anything and a workplace that could shift from their office to their bed with little notice. Their new work, Benched, an intimate rumination on athleticism and bodies that subvert the binary of disability, reflects some of this adaptability in the simplicity of its staging. As the two of us message back and forwards to organise a one-on-one performance, Main says they could meet me ‘anywhere with a bench’ or perform via Zoom. This is a show designed to work for COVID but also for Main’s endometriosis.

‘As actors, directors, playwrights, crew, creatives, theatre-makers, storytellers, we are in the business of creativity, imagination, and problem-solving,’ Main said in a recent speech at Rumpus. ‘We work with pure potential and possibility to imagine and realise new worlds onstage.’

If we can do all this, the artist and advocate suggests, surely we can imagine and realise an industry that meets the access needs of all artists and audience.

Read: Carly Findlay on centring disability in our latest podcast

I am constantly amazed by how unimaginative creative work places are despite being in the business of imagination. A good example of this can be found in rehearsal schedules. Most mainstage companies rehearse 10am to 6pm, five or six days a week for four weeks, a schedule that makes rehearsal inaccessible not only to many talented artists with disability but to parents, carers, those living regionally and artists balancing multiple jobs (which is of course the vast majority of artists).

Many companies start their planning with an inflexible deadline – opening night – rather than by asking the question, ‘Who do we want in the room and how can we make this work for them?’ Such questions could have massive ramifications for our industry.

Taking into account the access needs of disabled workers and artists benefits everyone: it builds work places that listen to the needs of individuals. As an educator, every adjustment I made to curriculum to work with the needs of neuro-diverse students made the course more accessible to everyone. As Sabuncu says, ‘everyone has access needs’.

At present, the demand that actors fit a four-week rehearsal period into their work rosters means that many actors are locked into casual work, a situation that does not necessarily utilise their leadership or creative capacities. A more accessible approach to scheduling could see our workplaces welcome more diverse teams and benefit the overall standard of living for arts workers, who currently exist in a perpetual state of job insecurity.

The creativity and inclusive collaboration with which companies tackled the last 12 months was inspiring. Across the country, community, flexibility and access was prioritised in a way that it seldom was before. As Main wrote in a 2020 ArtsHub article: ‘I haven’t seen so much theatre at any other time of my life as I have during the Covid-19 lockdown.’

The bare minimum that we can ask is that companies continue to keep the doors open for the whole community’s access needs. However, after the year we have lived through, learnt from, staged and re-staged through, after a year of conversations with disabled and chronically ill artists and students, I firmly believe that companies should to aim higher than access: you need these people not only as experts in access and art but in resilience, creativity, ingenuity and problem-solving.

As Liz Jackson, creator of The Disabled List says, ‘Disabled people are the original life hackers’. As we re-build and re-imagine, we need to continue learning from the last 12 months and listen to the deep knowledge of those who are way ahead of us.’