There’s a little place somewhere on your body which if touched in the right way engenders an uncontrollable reaction: a jolt; a visceral upshot over which you have no control.

Taboo art can have much the same emotional effect and the trigger of your response is just as subjective as the location of that one spot, making it difficult to determine where the line of what’s appropriate is drawn, or if there should even be a line at all.

Often overshadowed by the weight of its subject, taboo art can be difficult to understand. As we progress deeper into a more atheist and scientific society in Australia, a lot of what was once considered taboo – specifically sex and religion – are no longer received with such sensitivity. Instead, new taboos begin to emerge, such as racism, cruelty, slavery and even something as simple as smoking while pregnant. Events such as September 11th and the Holocaust are also taboo.

More than just simply offensive, taboo art can shatter typical conventions in cultures where certain groups are oppressed, open up a conversation about sensitive topics, and reveal the complexities and challenges of issues often deemed too provocative to talk about.

Mic Eales is an artist who tackles the taboo every day in his work by creating art that opens up a discussion about suicide, a topic that one can recognise as taboo in our society through selectively worded obituary notices alone. He recognises the importance of using art to tackle topic that is largely kept quiet.

‘The silence that goes with suicide, and talking about suicide, is deafening. It’s all pervasive and art provides a voice to talk about those experiences and the pain,’ he says.

‘I think that art is a way of speaking about suicide without actually verbally saying anything. You speak though your art. I’m positive of that.’

There is no doubt about the positive impact of Eales’ work in tackling a topic that should no longer be taboo, but what about breaking taboos in a way that is offensive instead of simply sensitive?

Offensiveness differs largely depending on culture. Sigmund Freud argued that the only two universally recognised taboos were incest and patricide. While that may not be completely correct, the difference between what is taboo and what isn’t can be as thin as the edge of a knife and is dependent on the time, and the place, that the artwork is shown.

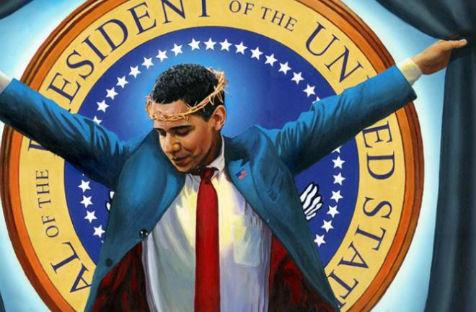

Recently, in America, a picture of Obama as Christ on the cross broke a major taboo for the Christian Right there. Here in Australia; however, the image isn’t likely to produce more than a titter from the largely secular community. The image, in turn, even had conservative commentator Glenn Beck, who was clearly offended by the work, using it as an argument for free speech.

The Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA) has curated an exhibition examining the subject matter, TABOO, to open on 19 December. TABOO examines the many faces of this type of art, focusing on the attitudes held in traditional societies from across the world.

Curator Brook Andrew says the exhibition aims to raise issues of censorship through ‘daring’ or ‘disrespectful’ devices.

‘TABOO aims to re-visit arguments and decisions made out of fear and trauma that have now become verbatim to shut down discourse or even to influence good value in debate, creativity and culture,’ says Andrew.

‘TABOO aims to remove these barricades by juxtaposing ideas that open other strategies to enable visibility, discussion and accessibility.’

In Australia, one of the most famous contemporary examples of a work breaking taboo was the photography of Bill Henson, who took pictures that were deemed to be so offensive even the Prime Minister at the time felt the need to comment. He broke the taboo of the pre-adolescent, one where few dare tread, but in doing so engaged the entire nation in a discussion that was much more worthwhile than the usual water cooler banter.

Is art like Henson’s offensive? To some, yes. But it does serve a valuable role in our cultural community, and demonstrates the importance of freedom of speech, something that taboo art has been championing for centuries.

But basically any art that is more than a pretty picture can be taboo to someone, somewhere and censoring some and not others based on personal curatorial decisions can be fraught with danger. One just needs look at the outraged caused when in 2010 artist David Wojnarowicz, who died of AIDS in 1992, had his video A Fire in My Belly removed from the Smithsonian museum after protest from the Catholic Church. At the time, some artists felt that this reflected a damaging attitude in larger American art institutions to favour outside interests over those of the artists.

There will always be a sense of moral panic, such as that which took place at the Smithsonian in 2010, when it comes to anything new but his panic can be reflective of a positive change. Just look at the emergence of the independent theatre sector in India, which faces strong opposition from the country’s religious population. In breaking cultural taboos – such as kissing in public – these films are reflecting the stories of every day Indians in what could be argued in a much healthier way than the song and dance escapism of Bollywood.

‘I think the audience in India is changing so much that films that people would not even think of making 5 years ago are becoming big box office hits because people are just ready for newer kind of narratives, newer stories, edgier stories. I’m sure when these films are also released in India they will find an audience that is more accepting and welcoming of this new change,’ said Indian Film Festival Director Mitu Bhowmick-Lange in a 2011 interview.

Stand up comedy is an art form that is often seen to push the boundaries of what is appropriate. Just look at the controversy surrounding the Sarah Silverman rape joke, or pretty much anything Frankie Boyle has ever said.

These artists might provoke uncomfortable feeling or an outright lividness but art has been breaking taboos for centuries. We should be wary of it, but let’s not censor it.

TABOO will run at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney from 19 December to Feb 2013. For more information visit the MCA website.

_Encounters-in-Reflection_Gallery3BPhoto-by-Anpis-Wang-e1745414770771.jpg?w=280)