Image: Wikimedia

When Sue Woolfe was in the midst of writing her third novel, The Secret Cure, she struck a problem as old as art: creative block.

‘It was one of those novels that first seemed like the kind that novelists dream of, where the plot came immediately, before I’d even begun. The problem was I got stuck there. Knowing the plot seemed to chain me down and stifle my imagination,’ she said.

But unlike many before her, Woolfe had access to modern scientific knowledge to help her through the difficulty.

‘I started to sleuth through neuroscience to find out what neuroscience knows about creativity and creative writing. Neuroscience says nothing about creative writing but an enormous amount about creative thinking and neuroscientists have studied it for a long time. It really got going in the 1950s so there is a big body of knowledge. Originally study focussed on biographical studies of famous creators until the technology improved, first with the EEG machine and then the fMRI machine. That brings us up to now. We certainly don’t know everything about creativity, by any means, but we’re beginning to know the brain activities involved.’

Woolfe used the knowledge she gained and her experience dealing with enhancing creativity in her non-fiction book The Mystery of the Cleaning Lady: A Writer Looks at Creativity and Neuroscience, where she asks: ‘What does a fiction writer do to her mind to create fiction, and was I doing something wrong that jeopardised my own work?’

She also puts the insights neuroscience provides on creative thinking into practice these days in her classes on creative writing. ArtsHub recently asked her for some advice to help those of us who may similarly find themselves at a creative impasse.

Stillness is good

The first thing Woolfe teaches her students is something they already do, but often don’t know to value.

‘It’s just letting your mind go vague, blank, even dozy. I don’t mean have a wandering mind, but there is a skill I teach where you stop the chatter of the mind and stay in that zone for at first flashes, then for longer and longer periods of time.’

Woolfe calls this state ‘the lull’. It uses the brain activity which allows most creative thought – Arne Deitrich, a leading neuroscientist, argues that it may use different neural pathways than logical, rational thought uses. The scientific term is ‘defocused attention’.

The power of defocused attention may explain why a long walk can boost creative output and also why the housework may be an excellent way to balance the hours at your desk. ‘It’s something you do anyway when you are doing a humdrum task, walking or driving through the country. We did it naturally as children- then studies suggest it was socialized out of us. Everybody knows those times when some unexpected thought will flicker across your mind. Creative people know not to dismiss those thoughts, they are the treasure we’re all yearning for.’

Composers have long utilised the power of the still mind. Beethoven came up with one of his compositions while napping on a coach ride to Vienna and Debussy liked to gaze for hours at the River Seine, finding the sense of reverie stimulated his creativity.

Woolfe’s former student Ally Burnham, who is a writer on television show Sweet Jane and first learnt from Woolfe while studying writing for performance at NIDA, found the insight helpful for her own writing practice.

‘Sue Woolfe gave us the tools and the language to recognise it as the lull, and it’s surprising how just having words to describe this kind of thing makes it more tangible so you can discuss it. It demystifies it and then it becomes something you can practice and not something that just happens,’ said Ally.

Switch off the judgement

To help students access the lull, Woolfe begins class with an auto-writing exercise. Sometimes this involved a single word or visual prompt to help the students start.

The hard part was switching off your self-judgement, said Burnham. ‘It’s that judgement that locks you up and stops new ideas from coming. It’s the judgement on yourself that stops your creativity.’

The goal is to just write as free from doubt and analysis as possible. So just start writing and keep going for an hour. Don’t read back over your work because then you will start using the analytical side of your brain rather than the creative part. Understand that this is not going to be your best work, because that’s from the analytical brain, but is the time where ideas will come to you as you write.

As Sue Woolfe teaches, you need to create the clay before you sculpt. ‘You can’t judge the clay, you just need to tease out and encourage as many words first and get it onto the page,’ said Burnham.

‘You just have to trust in it because that judgement starts to come in and you start to think, “I’m just going to produce crap” and you think it’s not going to be any good. The most important thing is learning to ignore that judgement. It’s not so much about learning to be creative in these moments, but it’s about learning to turn off the judgement, it’s learning to turn off the analytical part of your brain, which will then just free up your creative brain. I really found that quite useful.’

Get bored

Burnham recommends inciting boredom. ‘Turn off the internet. Get off Facebook and away from all that stuff. It’s funny how just staring at a wall will turn off the analytical part of your brain. Eventually your brain will start entertaining itself when you’re bored enough and that’s the work you can put on the page.’

Know your brainwaves, by Denise Jacobs.

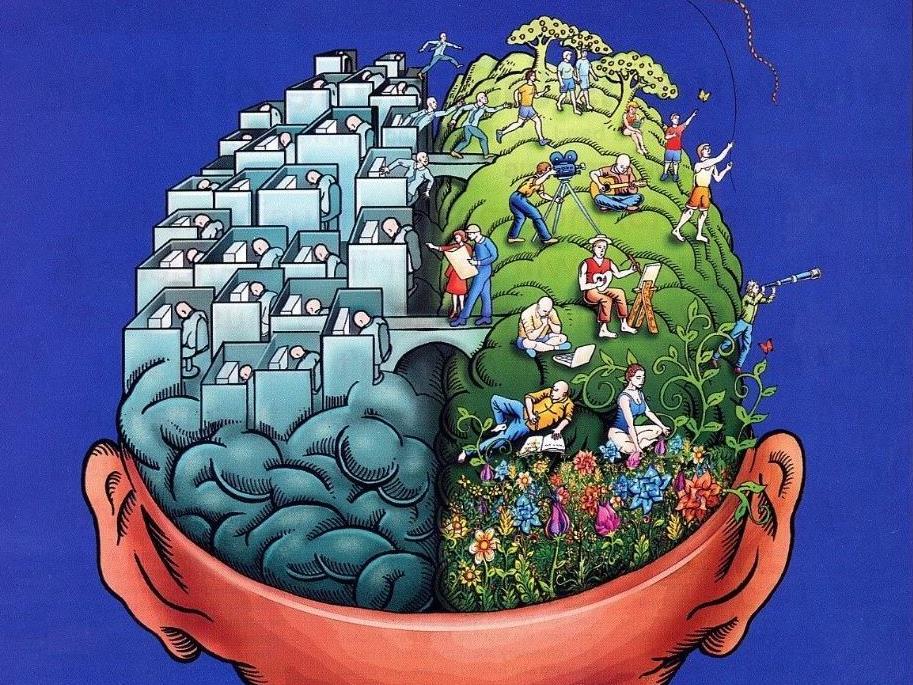

Burnham also found that a visual aid (like above) can help you understand what is going on in your own mind. The alpha waves, in the centre of this brain wave chart, are the moment when creativity is most accessible.

‘If you imagine a line representing a brainwave in the middle of the bar and it shoots up to the top – that’s what happens when your brain is stimulated by something like science or maths and when your brain is switched on. Then what the lull is for creative writing is if you start in the middle and then it dips down. When you get bored or when you’re just auto-writing and you shut off the analytical part of your brain, that’s this dip down and then it shoots back up even above where the top of the chart is and it’s this dip down that Sue calls the lull. That’s why she calls it the lull, because it’s this dip in brainwaves before it shoots back up.’

Now, Burnham doesn’t need to do the auto-writing exercises to get into a creative frame of mind and access the lull. Instead she has found that just having this knowledge of how her brain works means she is able to recognise when it is overstimulated and she needs to make herself bored before she can get creative. ‘You can practice this brain activity, you can practice entering the lull when you know what it is,’ she said.

Looking back on her initial writers’ block experience, Woolfe now recognises why the very things that she thought should have made her novel easier to write, actually made it difficult.

‘I think for me and probably for a lot of people I teach, writers’ block happens when you are forcing yourself along a preordained, planned path as I was trying to do. Given that I knew the plot – knowing too much- I had to invent ways to be in a state of not knowing,’ said Woolfe.

Meditate right

Another insight from modern neuroscience casts light on the value of a very old technique: meditation. Multiple studies show the power of meditation to alter brain waves and recently, researchers from Harvard University showed regular meditation has sustained effects on cortical thickness which affects sensory, cognitive and emotional processing.

For those seeking a creative boost, a study by cognitive psychologist Lorenza Colzato at Leiden University is particularly revealing. She found ‘open monitoring’ meditation promoted divergent thinking – the kind of thinking that leads to creativity.

Open monitoring meditation is a meditation practice where the individual is receptive to all the thoughts and sensations experienced without focusing attention on any particular concept or object. This contrasts with focused attention meditation, where an individual focuses on a particular object or idea.

Meditation has long been used by Japanese artists in ink painting and contemporary calligrapher Nadja Van Ghelue has found the technique essential to her work.

‘No methods are taught in Western art to educate and achieve a genuine creative state of mind. I discovered that this was not the case in the East. The calligraphers and painters of the East show a direct path to cultivate this creative state of mind. Their whole philosophy integrates life, spirituality and art, and art becomes a way of living,’ she said.

Sue Woolfe also takes people on overseas retreats to help them enhance their creativity: http://www.writingingreece.com