Content warning: this article makes reference to experiences of sexual assault, abortion and cancer.

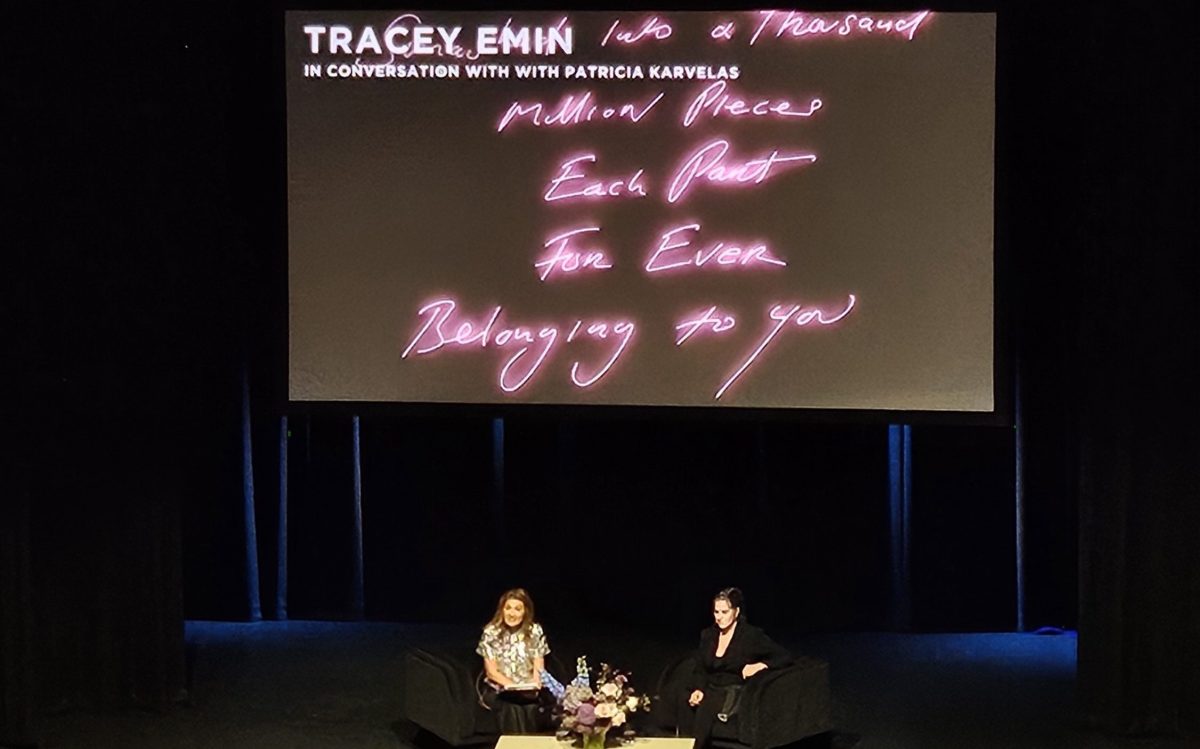

British artist Tracey Emin is an icon for many – a textbook artist one is bound to come across during contemporary art courses. It was a rare treat to meet and hear from the famed artist on her unconventional path in the art world at a recent talk presented as part of the NGV Triennial in Melbourne (Australia).

Emin was born in 1963 in Croydon, south of London, to a poor family and brought up in Margate on the Kent coast. An early school dropout at the age of 13, she stepped into society prematurely and found what lingered in its darkest corners. Despite being forced to return to school at 15, Emin says the time she spent in those dark corners were perhaps what drove her towards art.

‘The school I went to was for rough kids; all that was expected of me was to leave school at 16 and get a job in a factory. But because I’d missed so much of school already, they didn’t mind what I did as long as I went. I’d spend all day Wednesday doing art, Tuesday afternoons reading plays, Mondays writing stories – I basically did what I wanted and I absorbed what I wanted to absorb,’ she explains.

‘When I left school again, I packed two David Bowie albums with some clothes and went straight to London. I immediately fell in with the creative scene there.’

Emin was homeless during three different phases of her life, and countless times she says she came close to death – on the streets, intoxicated in her apartment (what spurred the seminal work, My Bed in 1998) and with her recent diagnosis of (and subsequent recovery from) bladder cancer.

Emin speaks of these experiences vividly, but always with a lightness of touch. This sharing of personal experiences, including abortion, homelessness and being sexually assaulted at the age of 13, stems from her unwavering desire to provoke empathy and compassion towards victims – to show the social constructs that compound the trauma.

Although she often views herself, and was viewed by others early in her career, as an “outsider” artist, Emin has a clear vision of what art is and ought to be. During her Melbourne talk, she revealed to the audience how she sees herself and what kind of artist she is.

Jump to:

The big break

While many would regard Emin’s inclusion in the 1997 Sensation exhibition at the Royal Academy as pivotal, she herself is quick to dispel that view.

Sensation showcased the collection of advertising superpower and art collector, Charles Saatchi, with many provocative works by the Young British Artists (YBAs) including Damien Hirst, Marc Quinn and Sarah Lucas. But Emin says, ‘I never really benefited from the show, because I always refused to sell Charles Saatchi work [until much later] and he bought my tent [Everyone I Have Ever Slept With (1963–1995)] from the secondary market.’

She explains: ‘In the mid-80s, when my contemporaries were doing Frieze, I was up a mountain in Turkey, doing watercolours of mules – I was coming from a very different direction.

‘My big break, for me, came on a show with Jay Jopling in 1993, My Major Retrospective, and then it was the Minky Manky show in 1995 at the South London Gallery. That’s when I first showed my tent and it caused a big sensation.’

For Emin, her 1998 work My Bed was a state of being, more specifically, Emin’s state of being the time she woke up four days after getting really drunk following a bad breakup. Her apartment was a mess, stocked up with dirty dishes and greasy glasses; the bed was piled with soiled underwear and used condoms. ‘I looked at everything and thought, “Oh my god, this is so disgusting”, but I also had this other view that this bed and this room kept me safe and alive. In a split second, I saw everything in a sort of heavenly white space and I thought “Gallery”,’ she says.

What comes with comfort and security

After Saatchi’s relentless phone calls and a destined meeting, Emin got to know the collector well and he become an avid supporter of her work in the early 2000s. ‘Charles Saatchi really propped up a lot of artists and changed their lives. From a sale of my work, I’ve managed to buy a house and it changed my life,’ says Emin.

‘For me, to be able to get a house out of my art was like the greatest thing ever – it was a miracle. It wasn’t about the money; it was about comfort and security.’

But did this change her as an artist? Or, as Emin puts it, the more straightforward question is, did it make her art less good?

‘A lot of people think that if you come from hardship and a rough background, it spurs you on, it’s what feeds you. And then suddenly you go into the comfort zone and you become wishy-washy or you lose your direction.

‘But for me, the opposite happens. The most confident I am is now and I don’t have to worry anymore. I get to just focus on my work and my art.’

Read: Exhibition review: NGV Triennial 2023

Even if Emin may be spending less time making art at this point in her career, she is finding herself to be more efficient. ‘In my early 30s, I would work 18 hours a day, almost every day. As you get older, you work fewer hours, but with more intensity and more focus – it’s more exhausting. But you know exactly what you’re going to do and everything is set up for you to do it.

‘When you’re young, you’re experimenting and you’re making loads and loads of mistakes. What makes you the artist that you are, are the mistakes.’

Defining yourself as an artist

It becomes quickly apparent that Emin’s perception of herself and her practice may be different to how it has been framed by historians. She particularly dislikes the label “confessional artist”.

‘When I was younger, my work was deemed as being confessional, but I’m quite expressive. You don’t say [Vincent] van Gogh was confessional or that Rembrandt was confessional. If you go through history, there were a lot of men that were expressing themselves and their emotions, but no one would call them confessional.

‘I think part of that is a thing that men say, “she’s confessing”, like I’m throwing up and spilling the beans.’

She continues: ‘I was making work about how it feels to have an abortion, which I thought was really important 20 years ago and it’s still f***ing important now. This subject should have always been spoken about, instead of being taboo… But, for that, I was branded “confessional” – nobody saw it as, “Oh, she’s making art about a really important subject”, though they’ve finally caught up now.’

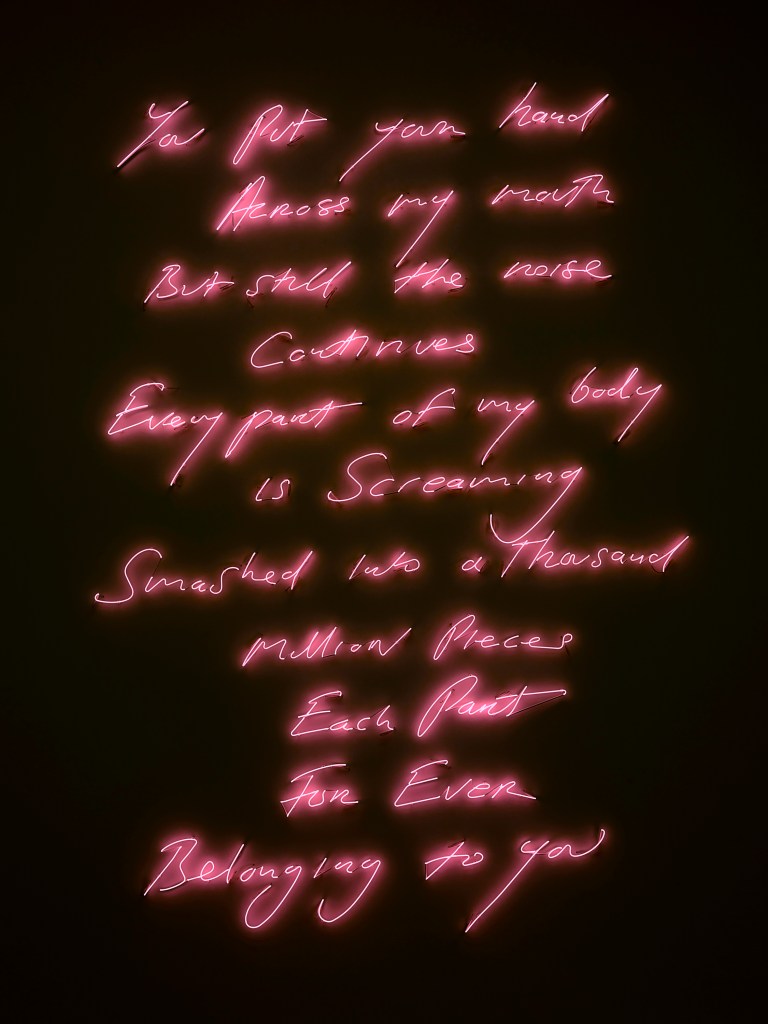

Another long-held perception of Emin is around her neon text-based works, what some may see as the crux of her legacy. At this point in her career, Emin says she rather despises writing, especially when it involves a deadline.

‘I realise I’m not a writer, but I always say to Harry [Weller, Creative Director of Emin’s studio] when I’m really old and can’t move, I’m just going to dictate my memoir.’

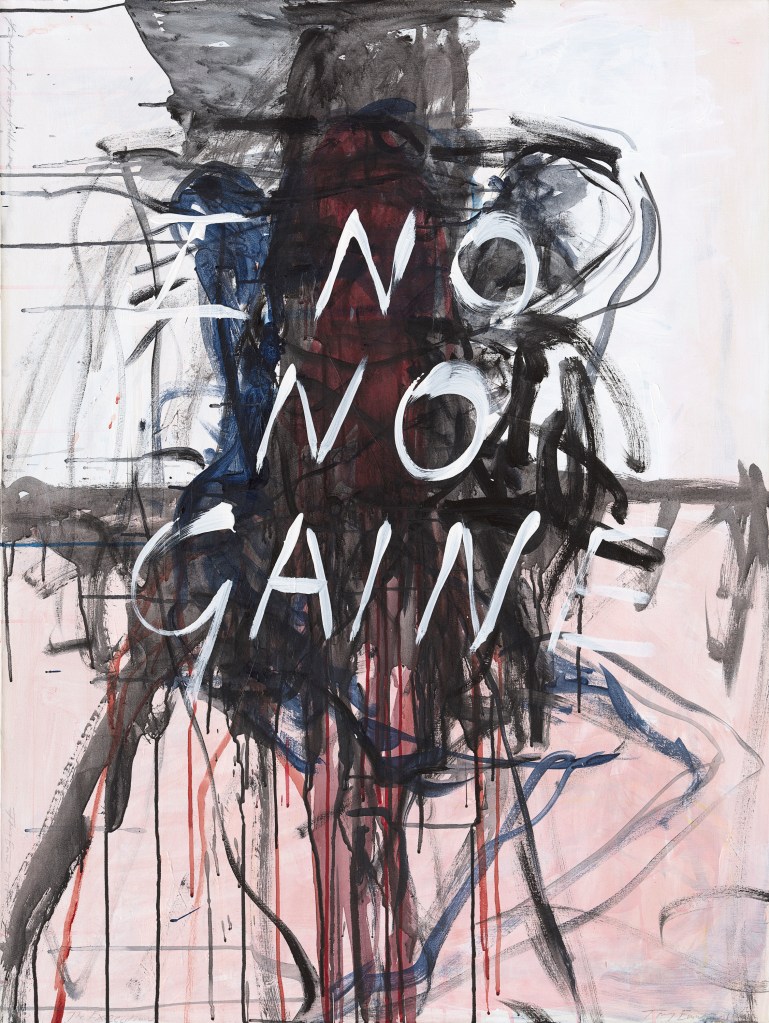

Now, Emin sees painting as an integral part of her oeuvre. ‘I loved writing when there was no room for me in art… In the 90s, when you did figurative painting, people thought there was something mentally wrong with you.

‘Now, 30 years later, I’m so happy painting. The fluidity is like another entity that comes out of me. It makes me feel good, feel whole; it frightens me and scares me. It’s like running through the woods with wolves chasing me and I love it.’

It has to do with ego

‘Tell me a great artist who doesn’t have a massive ego, it’s not possible,’ says Emin. ‘That ego is what drives you to be singular, not afraid to carve yourself out a niche and the direction that keeps you going. This then creates a vortex for other people to come behind and support you – that’s the way it works.’

She recalls a time when this ego was challenged, put to sleep even, as she lay sick in bed while her artworks were at an exhibition in Oslo, alongside works by Edvard Munch (1863–1944). Munch is a bit of an idol for Emin, and to be able to exhibit alongside him was a dream come true.

She explains: ‘At that moment, the biggest moment of my life and my career, I just couldn’t be there and [my] ego was pretty much zero. I was in bed and all it was, was content and happiness. I thought, “Wow, there’s another way of going forward, which isn’t this ego-macho centred [approach]. You can be a really strong artist just from sitting in your bed and being focused and sincere as well.’

How to be happy

When Emin was diagnosed with bladder cancer in 2020 and told she may only have six months to live, she accepted it. ‘It’s inevitable,’ says Emin, ‘so I decided there was nothing I could do about the dying, but what I could do something about was the living.

‘My attitude changed overnight and I just suddenly became much happier… I survived surgery and got a second chance. I think whoever “they” are, they said, “She’s not that bad. She’s f***ed up quite a bit, she’s a bit stupid, but actually, she’s not a bad person. Let’s give her one more go and see what she does”.’

In the past three years, Emin has really lived up to the mantra of “living your fullest life”. For her, it’s about ‘doing the right thing, being in the right place at the right time, and everything to do with art’.

‘That’s my priority, to really focus on art. Art, again, has come to save me and picked me up – I’m very happy because of it.’

Emin is showing three small bronze sculptures that depict the female body in the NGV Triennial. Each embodies a strong sense of tactility and a pose in motion. Also a major acquisition is Love Poem for CF (2007), a five- by five-metre neon text work that is currently on display on Level 2, NGV International, and will enter the NGV Collection.

In Emin’s will, which she drafted the night before her surgery to remove her bladder tumours, was the idea for a foundation that supports artists. A few months ago, this came to fruition with the official launch of the Tracey Emin Foundation, which offers art residencies in Margate, where she grew up. Ten residencies are offered each year, and with ‘the best people coming into teach,’ says Emin. She adds: ‘There isn’t one single person that sets foot in Margate from the art world that doesn’t have to go there and do some tutorials.’

Emin concludes: ‘That’s me, living. I don’t want any more clothes, more cars; I don’t want any more of anything. I want to be happy.’

Live and in Conversation After-Hours: Tracey Emin was held in-person and online, moderated by Patricia Karvelas, on 29 November at the Capitol, Swanston Street in Melbourne’s CBD. Presented by the NGV leading up to the NGV Triennial.

ArtsHub attended the talk in person.