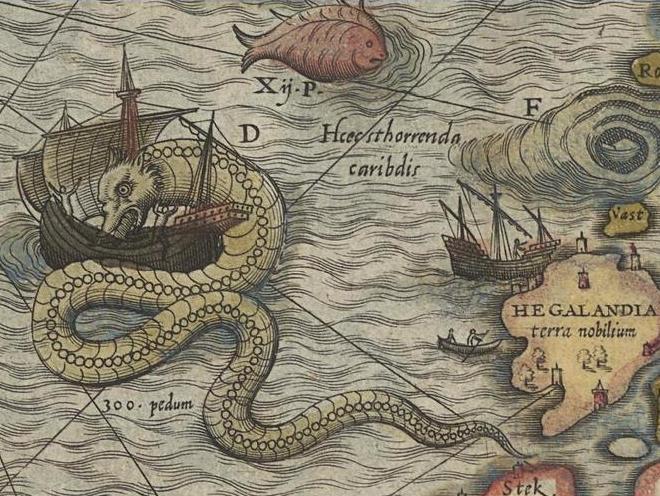

Fear of the unknown is a dangerous place, represented by ancient map makers with dragons.

‘Freedom of speech – in a global context – certainly doesn’t mean, nor should it, that anyone can say anything, anywhere.’ It was a powerful reminder by Alec Coles, CEO of Western Australian Museum (WAM), who tackled the thorny and very critical question whether museums are ‘safe places for unsafe topics’ at the recent Museums Australia Conference in Sydney.

Two things are colliding at the moment. We have a zeitgeist of embracing storytelling in the museum sector – the concept of championing and sharing many voices. But there is also a broader societal contraction, an adopted righteousness on one hand and a growing “nanny-state” on the other.

With festivals now for ‘dangerous ideas’ and an audience ever-more vocal, set against a global backdrop of actions such as the Charlie Hedbo office siege and the destruction of antiquities by militant minorities, the contemporary terrain for the “authoritarian” display – which museums have traditionally done for ages – is being held up to moral and social scrutiny.

Coles raised the example of last year’s Festival of Dangerous Ideas presented at the Sydney Opera House, which became embroiled in controversy over the invitation of Muslim writer and activist Uthman Badar who was to deliver the talk “Honour killings are morally justified”. Acknowledging that the internationally acclaimed event – which in the past has been a platform for agents such as Germaine Greer, Julian Assange and Salman Rushdie – had always ‘intended to be a provocation of a broader discussion’, Coles suggested there had to be a limit to freedom of speech for cultural institutions.

‘The Opera House was acting as a safe post for not only unsafe ideas, but dangerous ones,’ he said. ‘This extreme example is instructive of the opportunities and the threats in setting ourselves up as places of expression and debate – that the views and positions expressed are not necessarily our own.

‘It teaches us that there are no such thing as a safe places and sometimes the ideas are just too unsafe.’

‘Safe places for unsafe ideas as a phrase is a very effective piece of shorthand, but in reality how accurate is it? How prepared are we as a sector to embrace these principles? How prepared are our government and stakeholders for us to engage with them and what are the implications of providing a space for those more extreme views?’ They are pertinent questions that Coles raised, prompting a discussion within industry.

Havens for safe-keeping

The concept of museums as safe places has hit the global spotlight in recent years, with media report of antiquities destroyed and museums raped in areas of conflict.

One story emerged last year that reached Australian shores. Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures was an exhibition of objects saved by a group of courageous staff from the National Museum Kabul, and presented by the WAM, as well as and Melbourne Museum, Queensland Museum and the Art Gallery of NSW. More than 1.5 million people saw these pieces on its international tour.

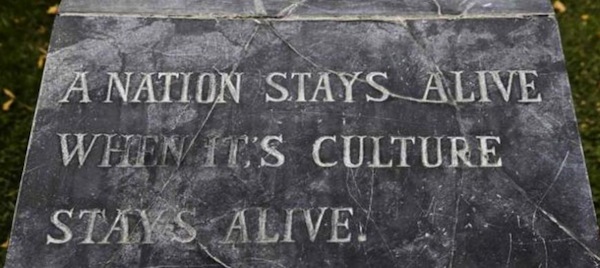

Cole said: ‘The spirit of these people is visualised in a plaque in front of the museum (today) – a nation stays alive when its culture stays alive – it is the touchstone for all of us and reminds us that culture is driven by the freedom of expression.’

National Museum of Kabul; Source Die Welt

‘The concept of safe places for safe ideas seems decreasingly redundant in this context,’ Coles continued, adding support and sympathy for our museum colleagues in Syria and Iraq. ‘We have to accept that there is really no place that is complete safe, and that every idea is unsafe to someone.’

Harbouring controversial speech

Coles made the point that exhibitions collate, set out to provoke, and also serve to humanise and make accessible to view some subjects that are sensitive. He championed Daryl Karp’s work at the Museum of Australian Democracy for their annual exhibition Behind the Lines: The year’s best Political Cartoons.

It is a particularly strong reminder of the freedom our museums have when viewed in the light of January’s Charlie Hebdo incident where 12 French journalists and cartoonists were killed, and the more recent Texas shootings, also over a cartoon exhibition.

‘Reflecting on that, the cartoon is one of the last bastions which we can express dissent,’ said Coles, adding that he wrote a speech the week of the massacre supporting the space for the freedom of speech but questioned the brinkmanship of Charlie Hedbo and citing the classic quote that is often misattributed to Voltaire, ‘I disagree what you are saying, but I defend to the death your right to say it.’ It was his biographer Evelyn Hall that stated it.

Although not mentioned by Coles, Australia has also had its share of pressure points in the visual arts sector, cases that push the boundaries of pornography in the lines of society and law, such as last year’s court case over Paul Yore’s work at Linden Art Centre, the now infamous case of Bill Henson at a commercial gallery and then later withdrawal from Adelaide Biennale invitation, and recent retraction of works held in our major state collections by the artist Dennis Nona.

Ethics, law and governance are overlaid in the decision making process that often become the pointy end of media scrutiny that blurbs the platforms for freedom of speech through creative expression.

The question we must ask again is, prompts Coles, is where do the divisions lie for the museum? ‘Rigorous speech is an imprecise concept; it need not focus on the area of opinion,’ said Coles, how we position and present those voices in the museum sector is an increasingly sensitive question we face today.

Australia’s unsafe stories

Museums grapple daily with their use and presentation of diverse voices. In Australia, Coles cited the Australian National Museum’s handling and positioning of “the history wars” and the Maritime Museum in Freemantle for its work towards presenting alternative narratives that ‘correct what it considers a misrepresentation of Australian history’, his own need for navigation at WAM, as the Museum prepares to exhibition the “asylum seekers boat” that came ashore at Geraldton in 2013, and which the Museum acquired.

Photo Sarah Taillier ABC News

Accused of wasting public funds, Cole has stuck by his determination to document the contemporary history of Australia and, in particular, one that speaks of Western Australia.

‘This is supposedly an unsafe subject (asylum seekers). In displaying the vessel, which we will, and inviting comment, which we will, we are trying to encouraging debate and do not shy away from difficult issues, but above all gives a voice to the people of WA to express their views.’

Access versus trust

The growing trend of democratising the story does present problems. Museums do not have the resources to check every comment that is added to the collective narrative; stories passed on from one generation to another are riddled with errors – despite entering the domain as social historical record. In this current Anzac Centenary moment that issue is more prevalent than ever.

Coles warned that his new domain of popular commentary – with the every widening social media sphere – is a what we more commonly call a double-edged sword. He cited the recent dismissal of SBS journalist Scott McIntyre over “inappropriate” Anzac Tweet, might be ill conceived, insensitive and immature but that it was a sobering blow to the freedom of expression ‘when (he was) actually dismissed because he expressed an anti-establishment position.’

‘I staunchly (champion) WAM’s principal of many voices…of being a safe place for unsafe ideas, but I do so in the full knowledge that may lead us into some dangerous and uncomfortable places that you sometimes would rather not be,’ concluded Coles.

Cole concluded with a proposition for the room: The new question before us, as museum professionals, is will we risk eroding the trust we’ve built by appearing to be joined on the back of the deception that museums are pillars of truth, or will we seize the opportunity to build new trust by reaching outside the establishment?

Alec Coles presented these arguments at the Museums Australia Conference, presented at Sydney Town Hall. A full transcript of his speech is published on WAMs website.

_Encounters-in-Reflection_Gallery3BPhoto-by-Anpis-Wang-e1745414770771.jpg?w=280)