I was in high school the first time I ever saw an Asian woman play a lead role in a major TV show. And it was not until I was well into my 30s before I came across a female Asian main character in a fantasy book. In the books, shows and films of my youth, Asian characters were rare; if one was present, they were almost always the unattractive, nerdy sidekick.

While I perhaps didn’t realise it at the time, the lack of Asian representation in mainstream Australian media had a profound impact on my sense of self – and my acceptance (or lack thereof) of my cultural identity. I used to dream of going to sleep one night and waking up blonde-haired and blue-eyed, just so I could fit in better with kids at school. Growing up, being Asian made me feel like an outsider, and somehow lesser-than.

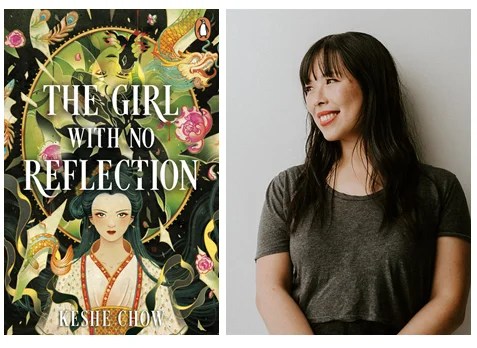

Thankfully, those feelings eased when I reached adulthood, a time that coincided with increasing positive depictions of Asian women in the media. Which is why, when I set out to write my debut YA romantasy novel The Girl With No Reflection, it was important to me to write it with an all-Asian cast. I’d been inspired by the work of East Asian young adult fantasy authors such as Chloe Gong, Elizabeth Lim, June C L Tan, Joan He, Judy I Lin and so many more.

It wasn’t always like that, though. When I wrote my very first novel, a speculative sci-fi thriller, it had an entirely white cast, because that’s what I thought I was “supposed” to do if I ever wanted to be published. And at the time that belief was probably true. Back then there was a distinct lack of diversity in literature, and even authors of colour – such as the incredible Tahereh Mafi, who wrote the wildly popular Shatter Me series – stuck to writing predominantly white main characters. I’m so grateful to the aforementioned Asian authors who paved the way and showed me that, yes, stories about people like me do matter.

Read: Book review: Peripathetic, Cher Tan

The Girl With No Reflection draws inspiration from several places. At its core, it’s a retelling of a short story called Fauna of Mirrors by Jorge Luis Borges. According to Borges, the story originally had roots in Chinese folklore, though subsequent analysis has failed to draw a direct connection. Regardless, when I stumbled across Borges’ story late one night I felt it was the perfect foundation upon which to build an unapologetically Asian story.

Incorporating Chinese mythology – such as the Chang’e and Hou Yi (Moon Goddess and Archer) myth, the myth of the carp and the Lóngmén (Dragon) gate, Chinese imagery about dragons and phoenixes, as well as traditional Taoist beliefs – allowed me to craft a narrative that paid homage to my heritage. While the book can certainly be enjoyed by readers unfamiliar with these myths, I do believe it will be appreciated even more by those who are familiar with Chinese folklore.

The other thing I wanted to pay tribute to was the strong women in my life: my mother, who immigrated to Australia with two tiny children, and who started out with no furniture, no car and not even a pot to cook in, and who used to walk miles just to get groceries, carrying me in her arms the whole way. And my grandmother – my Wai Po – who raised nine children in a time and place where women had little freedom and fewer choices.

In recent years, romantasy as a genre has exploded in popularity. While fantasy with heavy romance subplots has always been around in one form or another, especially in the indie space, it’s only been in recent years that mainstream readers and traditional publishing have truly embraced it. Romantasy, a word that’s a portmanteau of romance and fantasy, often explores feminist themes. As author Megan Scott says, ‘Romantasy gives women the possibility of being powerful … in a way that’s not threatening like it is in real life.’

In romantasy novels, the main characters display tremendous strength and resilience, frequently in the face of world-ending challenges. They have both agency… and attitude. These were attributes that I wanted to write into my main character, even if it wasn’t strictly historically accurate. Throughout Chinese history, women were often constrained, not only by customs and social mores, but physically too – as evidenced by the brutal and infamous practice of foot binding. While there are definitely examples of strong women throughout the various dynasties of Imperial China, they were often only able to obtain power and influence through subverting societal expectations.

While I wish I could say that the restriction of female freedom is purely historical, in some ways it’s as relevant now as ever. Even to this day, Asian women are expected to be meek and subservient, and part of the “model minority“. I wrote this book to centre Asian women in the narrative – to explore what it might mean to be a young Asian woman in a largely patriarchal society. To pay respects to those who showed strength not because of these expectations, but in spite of it.

Read: Is romantasy killing Australian literature?

Although romantasy is fabulous at portraying strong-willed, independent women, intersectionality is still sometimes lacking. Main characters can be female, or persons of colour, or queer, or disabled – but rarely, if ever, a combination. Recently, the US-based romance bookstore chain The Ripped Bodice published the results of its annual ‘The State of Racial Diversity in Romance Publishing Report‘. This survey focuses specifically on romance in the US publishing industry, but there is likely to be some crossover with romance-adjacent genres such as romantasy and women’s fiction.

In 2023, while some publishing imprints had greater than 10% of romance authors identify as BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and people of colour), many imprints were less than that. Considering almost 40% of the US population identify as BIPOC, this suggests that there is still some way to go with regards to championing diversity in romance and romance-adjacent genres in the US, and likely in Australian YA fiction, too.

As a Chinese-Australian woman who grew up in the 1990s, The Girl With No Reflection has everything I wish I’d read as a teen: Asian women taking charge, kicking butt and being the architects of their own stories. More than anything, even though there’s still room for improvement in terms of increasing diversity in the fantasy genre, I’m heartened by the fact that future generations of Asian-Australian girls will grow up seeing themselves on the page. It’s an incredible privilege to contribute, even in a small way, to that.

The Girl with No Reflection was published by Penguin on 6 August 2024.