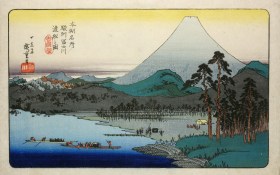

Bill Henson’s Untitled from Paris Opera project (1990) touring from the Wesfarmers Collection.

The landscape of Australia’s corporate art collections has changed dramatically over the past decade.

With the turn of the millennium, we witnessed a surge of companies selling off their blue chip collections. Art was no longer viewed as a justifiable investment or valued as a reflection of corporate vision.

Often the de-accessioned artworks reflected the tastes and nationalistic aspirations of the founding principals of those firms – usually early 19th century blue chip Australian art – which had become so valuable that they no longer made sense as ‘office decoration’.

It was a natural evolution that company boards felt compelled to sell their collections to better activate their corporate investment.

How they used those funds is where it gets interesting.

Collections lost to the hammer

This corporate art fire-sale has taken many guises over the past two decades.

For some it was the simple sell-off of assets on a corporate balance sheet; for others the perceived “value” of investing in the arts was maintained but needed a facelift – either choosing to engage in more publically branded philanthropic activities, like sponsoring exhibitions, art events and awards instead, or realigning their collection to trail-blazers through emerging artists, installations, digital and new media art.

Simply, it came down to a realignment of brand.

The loss to the art world has been great over recent years.

The sale of the multimillion-dollar Fosters Group Collection in 2005 for $14.4 million (including buyers premium) remains the largest, while chemical company Orica’s collection came a close second, de-accessioned for $13.2 million in 2001, paid by Western Australian and Channel Seven’s chief, Kerry Stokes. He folded some into his personal holdings under Australian Capital Equity group and auctioned the balance.

Fosters is a typical story. Largely amassed in the 1960s and 1970s by the former Elders IXL company, it is believed to have added only one painting since 1990 when the company became Fosters. Chief executive Trevor O’Hoy said, at the time of the sale, that the collection was being sold to ‘maximise shareholder value’. Art was no longer seen as a ‘strategic fit for a beverages company’.

It was a sentiment echoed by Fairfax’s chief executive, Fred Hilmer. Fairfax liquidated their collection also in 2002, opting to display the work of staff photographers instead. ‘The message is that I want to show off and be proud of the great work that the people who work here do,’ he said.

Similarly, corporate law firm Minter Ellison had a change of heart in 2015 sending 56 artworks to auction. Partner Katrina Groshinski said of their sale: ‘the move to an open plan office with less wall space led to a reassessment of the collection and the decision to dispose of the works.’

Firms such WMC Resources, Qantas, Coles Myer, BP Australia, AXA Asia Pacific, Unilever Australasia and property developer Austcorp (in 2009), have all sold their art collections.

Shell, Rio Tinto and Alcoa also unloaded their collections but rather chose to donate them to public institutions rather than take to auction.

While Shell’s $1 million Shell gift to the National Gallery of Victoria in 2002 marked the centenary of the company’s Australian operations, Rio Tinto – which also gifted to the NGV – was a less symbolic action. Its gift of 31 works from Fred Williams’ Pilbara Series valued at $6 million was reported for its $1.5 million tax break for the mining company under the Federal Government’s cultural gifts program.

Between 2002-2009 Alcoa returned its $3 million collection to the community via public institutions and health care organisations. It continues its philanthropy support through art events such as Sculpture by the Sea and the Melbourne International Arts Festival.

A new kind of collecting

However, not all corporate collections took the de-accession route. Those that stayed in the market, used their collections to position their brands, often with a greater emphasis on the contemporary and the global.

Wesfarmers Collectionis a case in point. The exhibition Luminous World, selection from its 900-strong holding, is now at the National Art School Gallery in Sydney as part of a national tour. Artists include Rosalie Gascoigne, Bill Henson, Robert Hunter, Susan Norrie, Rosemary Laing, Howard Taylor, Dale Frank, Paddy Bedford, Fiona Pardington (NZ), Max Gimblett (NZ) Brook Andrew, Timothy Cook and Nyapanyapa Yunupingu.

Wesfarmers is one of Australia’s largest listed companies, umbrella to the businesses Coles, BiLo, Liquorland, Vintage Cellars, Bunnings, Officeworks, Target, Kmart, plus resources and energy production and export, fertilizer and chemical companies and industrial and safety products.

The company engages in an active loan program and regularly commissions innovative, site-specific temporary artworks for its window foyer at Wesfarmers House in Perth.

Wesfarmers curator, Helen Carroll said that the, ‘Collection is also an investment in terms of shareholders. It is not an investment that we look at purely in financial terms. We don’t sell (it) for investment purposes; we are very committed to building up a repository of work.’

The simple message is why sell when you can build on that corporate history.

Over this same two-decade shuffle and sell off of the corporate art landscape, there has been a growing awareness more broadly of the contemporary brand, and how a competitive edge can be communicated through the projection of an innovative image.

Research Nina Pether explained: ‘The modern corporate art collection is no longer viewed as a totem of prestige to be enjoyed by a chosen few, nor is it a financial investment. It is a public display of a company’s image, embodying dynamism and change.’

American-born art advisor Barbara Flynn, who has been involved in shaping collections for several corporations in Australia, including Deloitte, ABN AMRO (RBS), UBS and Credit Suisse, agreed. She told ABC radio: ‘One of exciting challenges is to be bold and daring but never to make anyone feel uncomfortable.’

‘A challenge for us as curators (advisors) is to make sure the art isn’t compromised in that process. You don’t want to make the art the service the process of branding. The art always has to have its own integrity,’ Flynn added.

In Australia, Deutsche Bank, Deloitte, Allens Arthur Robinson and Macquarie Group are some of the firms that are leading the way in this new approach to corporate collecting, and remain very active.

Read: Six Corporate Collections you should know

Flynn says the budgets are not lavish. ‘They are really modest budgets so there’s always that awareness of caution and care in making responsible decisions. Often it is just one of innovation and embracing the new more than prestige – that is what the companies are interested in today.’

Art consultants help shape that image through the commissioning of site-specific, architecturally integrated artworks, the staging of challenging in-house exhibitions, and the use of artworks in their global branding strategy.

Flynn has been working with the accounting firm Deloitte, which has around 6,000 visitors to the public floors of its Grosvenor Place headquarters in Sydney each week. It was a number that precipitated a new way of thinking about the collection, and how it could be activated.

Since 2005 Deloitte as held two exhibitions a year sourced from Sydney and Melbourne’s commercial galleries, with artworks purchased from these for the permanent collection. The collection has also become an important platform for corporate entertaining.

Office architecture has played a key role in the change to corporate collecting.

With the invention of the open office plan and slicker aesthetics there has been less wall space for art and, with that, a democratisation of corporate collections.

A good example is Detusche Bank, which was one of the first to rethink the corporate art model in Australia with the design of its new headquarters by Lord Norman Foster in 2005.

Art Consultant Virginia Wilson worked with Deutsche Bank on the project, commissioning site-specific artworks to be incorporated into the building, works by Nike Savvas – a waterfall installation in a staircase – and Norwegian artist, Anna Karin Furunes who did made a work for a sound proof door in an executive space.

Similarly, Macquarie Group commissioned site-specific works for its Sydney headquarters redesign for 50 Martin Place, including a foyer work by Indigenous artist Daniel Boyd and an installation by Nike Savvas activating a light well.

Macquarie Group also stages art tours and talks as part of client or staff functions.

Helen Burton, the manager of the Macquarie Group Collection, said in an interview: ‘Art has become part of the Macquarie signature. In any office around the world Macquarie is recognisable by their logo and their art’.

BHP sold off the bulk of its Australian collection in 2002 at auction for $1.5 million. It then went on a shopping spree, reinvesting in around 200 new works that reflected its merger with London-listed mining giant Billiton, stating it gave ‘better view of where we hope we’re going and where we’re at. More of a contemporary, global-thinking corporation.’

Macquarie Groups has offices in more than 30 cities around the world. Julian Beaumont has been the chairman of the Macquarie Group Collection since its inception in 1987 and Felicity Fenner is the independent advisor to the Macquarie Group Collection, taking over the role from Nick Waterlow after his untimely death.

What is apparent today is that these are more than just blue chip national collections – they are global initiatives. The corporate collection of the 21st century must be a reflection of that brand to continue to be a sustainable entity.

_Encounters-in-Reflection_Gallery3BPhoto-by-Anpis-Wang-e1745414770771.jpg?w=280)