In darkened cinemas over the past twelve months, silent sheep, stoner detectives, male dancers and marooned astronauts lit up screens. The force awakened, cars sped fast and furiously, sexually active teenagers tried to outrun a mysterious foe, and a crumbling mansion taunted its latest inhabitant. Star-crossed lovers rallied against tribal customs, a French teenager tried to find her way in the world, fashion became a weapon against small-town gossip, and the two sides of the US housing crisis were exposed. A boxing franchise was reborn, superheroes were shrunk down to size, a comedian walked, talked and coped with fame, and the life and death of a music icon lost too soon was dissected in her own words.

Yes, 2015 was a great year for cinema, though that is hardly surprising. Each and every year offers up its own batch of shining gems among the ample average efforts and not-so-stellar offerings — and each and every year of movie-making and –going should be remembered for the former, not the latter. Once again, the best of the current bunch proved varied and vibrant, veering from brooding interpretations of classic texts to colourful contemplations of our inner emotions. So, looking at films that received a theatrical release in Australia since 1 January, which ten sit at the top of the heap?

When you leave audiences speechless with your debut feature, what comes next? Australian filmmaker Justin Kurzel chose to jump from Snowtown to Shakespeare, or from a dramatisation of the notorious bodies-in-barrels murders to an adaptation of the Scottish play. With Michael Fassbender in the titular role, Marion Cotillard as the fraying woman behind the usurper, and the likes of Sean Harris and Paddy Considine among the excellent supporting cast, the latest version of Macbeth is an acting showcase; however its sound and fury isn’t restricted to the performance realm. The command of mood demonstrated by Kurzel and his crew — including cinematographer Adam Arkapaw’s textured images and composer Jed Kurzel’s humming score — isn’t just meticulous, but mesmerising from start to finish.

Crafting a film that is savagely cynical yet still heartbreakingly beautiful is no easy feat, but in his first English-language feature, that’s exactly what writer/director Yorgos Lanthimos achieves. As he did with his previous efforts Dogtooth and Alps, the Greek filmmaker exaggerates social customs while also burrowing deep to expose the core of his chosen subject. Romance — specifically courtship rituals, the rush to matrimony and the favouring of monogamy — is his target, as satirised in a fictional, futuristic world that requires everyone to pair up or risk being turned into the animal of their choosing. Following David’s (Colin Farrell) attempts to turn loneliness into love inspires not only absurd and caustic humour, but also genuine and unexpected tenderness.

There’s no mistaking the buzz someone feels when the right piece of music brightens their day at the right moment. In Eden, aspiring DJ Paul (Félix de Givry) seeks out that sensation for more than two decades as he floats in and out of the French electronic music industry, watches acquaintances become successful as he languishes, and struggles through a parade of unsuccessful romantic encounters. If his experiences feel ripped from reality, that’s because helmer Mia Hansen-Løve fashioned the script both with and partially based on the life of her brother, a former DJ himself. Together, they offer a portrait of chasing a dream, and of the surrounding scene, that pulses with an astute soundtrack and simmers with an insider’s understanding.

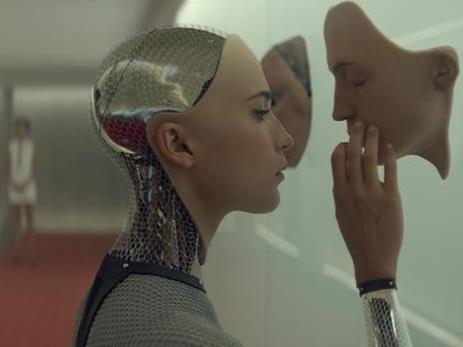

On paper, Ex Machina is the stuff that cinephile’s dreams are made of, serving up the filmmaking debut of The Beach author turned 28 Days Later…, Sunshine and Dredd screenwriter Alex Garland, plunging into a sci-fi scenario that pits humanity against artificial intelligence, and bringing Oscar Isaac, Domhnall Gleeson and Alicia Vikander along for the ride. On the screen, it becomes more than just the sum of its incredibly impressive parts — and transcends its obvious fondness for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, too — as it tests a humanoid robot’s interactive skills, toys with the perspectives of its characters, and twists its tale into a polished yet perceptive puzzle of philosophy and technology.

It might have taken thirty years; however when an Australian cinema icon finally returned to screens, it didn’t disappoint. In what proved an astonishingly good year for follow-ups to beloved franchises, Mad Max: Fury Road offered up the type of long-gestating installment audiences couldn’t ever have imagined would actually come to be, let alone in such an adrenaline-fueled manner. Writer/director George Miller used the past to build a new future, as the titular character once again navigates a post-apocalyptic environment. Of course, Tom Hardy’s interpretation of the unlikely hero originally played by Mel Gibson is far from the feature’s only highlight, with its high-octane action and Charlize Theron-led feminist thrust adding to a frenetic and finessed overall package.

Most films for children dare not speak of the virtues of sadness, or champion taking the good with the bad — but Inside Out isn’t most films, nor is it exclusively aimed at younger viewers. Ranking among Pixar’s best, it immerses audiences of all ages in a simple yet ingenious scenario, this time crawling through the recesses of a pre-teen girl’s mind, and pondering the results when her feelings, personified, have their own feelings. A creative and enchanting feature bursts forth, finding inventive ways to cope with intricate thoughts and emotions. A perfectly cast suite of voice actors assists, including Bill Hader, Mindy Kaling, Phyllis Smith and Lewis Black — and, of course, Amy Poehler as the most appropriate and endearing manifestation of joy imaginable.

A Most Violent Year

First, J.C. Chandor tackled the global financial crisis in Margin Call. Next, he charted the aftermath of a traumatic solo sea voyage in All is Lost. His third slice of crises-fuelled lives comes in the form of A Most Violent Year, as set during New York’s crime-ridden period that gives the film its title. Businessman Abel Morales (Oscar Isaac) attempts to keep moving onwards and upwards, but his choices — trying to steer his oil transport company towards bigger and better things, as well as his wife (Jessica Chastain) and family — drag him in the opposite direction. The conflict of trying to endure, survive and thrive in a capitalist society has rarely felt so insidious, nor as handsomely acted and shot.

History might be remembered as a series of big events and acts; however it is formed in small moments. Selma understands this; the film tells of attacks, speeches, treks and demonstrations, but it dwells in the space around Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. (David Oyelowo), his loved ones and advisors, and the others united in his quest for equality. Indeed, director Ava DuVernay hones in on the minutiae to strengthen the broader story, both in her handling of the material, and in her use of one chapter the of civil rights movement as the movie’s focus. The feature’s most climatic scene, depicting the physical clash that eventuated during the Selma to Montgomery marches in 1965, isn’t just a memorable culmination of her efforts, but demonstrates the grace and power that results from her approach.

Sicario

In Sicario, a by-the-book FBI agent (Emily Blunt) discovers the other side of the U.S. government’s attempts to assuage the influx of narcotics from Mexico. Recalling Zero Dark Thirty, a seemingly straightforward situation takes a turn for the complex — thanks to the involvement of two government contractors (Josh Brolin and Benicio Del Toro) — and so does the surrounding procedural film. After Incendies, Prisoners and Enemy, director Denis Villeneuve once again tells a tough tale and crafts a tense movie that can’t be considered easy viewing. Grit and murkiness reigns, be it in moral quandaries, weary yet resilient performances from the central trio, or sunlit visuals lensed by 12-time Oscar-nominated cinematographer Roger Deakins.

Phoenix

The sixth teaming of writer/director Christian Petzold and actress Nina Hoss is a haunting and fractured affair. And while Petzold bases his script on a scenario rife with the past casting a shadow over the present, then plays with duality and doppelgangers within such circumstances, it’s not just the post-World War II story he delves into that proves both lingering and multifaceted, but the manner in which he tells it. Phoenix is a film of stylistic savvy to match its spiraling plot, inspiring comparisons to the work of Alfred Hitchcock for a reason. Plus, it gifts the ever-impressive Hoss with a role and a song that won’t soon be forgotten, with the latter as quietly powerful as the former.