Peak body Arts Access Australia ran a virtual forum last week called Meeting Place. There is a sense of frontier boldness as this particular sector embraces emerging technologies to tell new stories, from different points of view.

British experimental media artist Jane Gauntlett delivered the Forum’s major keynote speech, delving into the use of digital headset storytelling – and their capacity for immersive and intimate experience – as a way to share her experience of living with a disability.

We are happy to share an extract from that speech.

It is 7: 30am and I am sitting in a pub in central London. The pub was built in 1863 and it is a theatre pub, lit by chandeliers. I must add that I live above the bar…. I write stories and I explore using different platforms in which to tell them.

Let’s talk about space…. I’m going to do this because the experiences of owning my own space, the amount of space that I take up, finding space in my head, having space to do what I want, and working towards a space that I want to inhabit, have had a huge impact on my work and audience care.

I should start from the beginning. The first time I remember demanding to have my own space, I am five and I am in the bath. My younger brother is sitting in the bath opposite me. I have just started school and I’m way too grown-up for this.

I’m 14. My body is changing. As is the amount of space that I take up.

I’m 15 and I’m learning to play the piano. It’s very noisy. My moods go from being happy to being sad, and from thinking I know everything to thinking I know nothing, and I’m very noisy about it. My family are giving me a lot of space. It is the first time that I’m conscious of the impact that I have on other people’s space.

I am 16, travelling in Costa Rica on my own. It is the first time I have had so much control over the space I want to inhabit.

I’m 25. I have been mugged, I am in a coma. I don’t have any control over the space I am in. Machines have control over my breath, my hydration and my nutrients. I wake up and I fight hard to walk and talk. I want to take control over my own space. And find new ways to do that.

Later that year, I had my first epileptic seizure. They happen regularly. I have them in public often. Strangers place their belongings under my head and take me in their arms. They wiped the blood from my face and invite me into their personal, physical space. They hold me until I am in a space that I can navigate. As soon as I’m able to stand, I announce that I am fine and try to leave, and make an excuse to do that. I guess that this is my survival instinct, and an immediate attempt to reclaim my space.

I am 26. I am exploring different spaces. Spaces to socialise, and spaces to work. I don’t fit into any of the spaces that I did before the attack. I feel that I’m alone in somebody else’s space, and I’m lonely. I’m finding a challenge to communicate with my partner and my friends and my medical team. I try to find alternative ways to communicate.

I start writing interactive audio pieces, and I use a Dictaphone to record my experiences from my perspective. I use this concept to invite people into my space. I use this as a tool with which to claim the space in my voice. I have pre-recorded arguments with my partner, and pre-recorded appointments my medical team, pre-recorded conversations with my friends. By doing this, I’m finding new ways to own my own space, both physically and verbally.

I wanted to explore whether what I’d learnt about making these audio pieces could become collaborations. This was the beginning of my journey into what became a self-tailored professional space. This was the beginning of the In My Shoes Project. The project became a library of over 120 interactive audio and written experiences.

In 2009, I discovered video goggles …My plan was to share the world as I see it through my eyes. I had a pair of old school video goggles [that cost] £50. I had a Canon camera and a Dictaphone. My plan was to share the experience of an epileptic seizure that I had on the train. I titled it Waking in Slough.

A participant sits in a chair with a blindfold over their eyes and headphones in their ears. A performer in a paramedic jacket stands over them. I introduced myself to the participant. I give them my handbag and my fountain pen, my notebook and a bottle of water. I guide them into the video goggles and invite them to see the world through my eyes. Then the headphones, inviting them to hear the world through my thoughts. I step back and out of my space and they step into it.

I very carefully build the set of a train around them. I use a chair which represents a train share and a table which represents a train table. A mirror that represents the slipperiness and cold of a train window.

As I guide them through the seizure, I use things to change the smell and place things into the water to change the taste. It ends up with a performer who takes the role of the paramedic. It fits the performance, and it fits very neatly into my commitment to audience care.

I was inviting people into my space in a way that I had never done so before. For all intents and purposes, I had control over their space. [But] what I realised was that I didn’t have control over their experience.

I learned that the technology was not important. It was [not] what they commented on. Nobody said that the colour grading was amazing. Nobody said they want to go out and buy this technology…What they remembered was the story, what they saw and felt physically and emotionally.

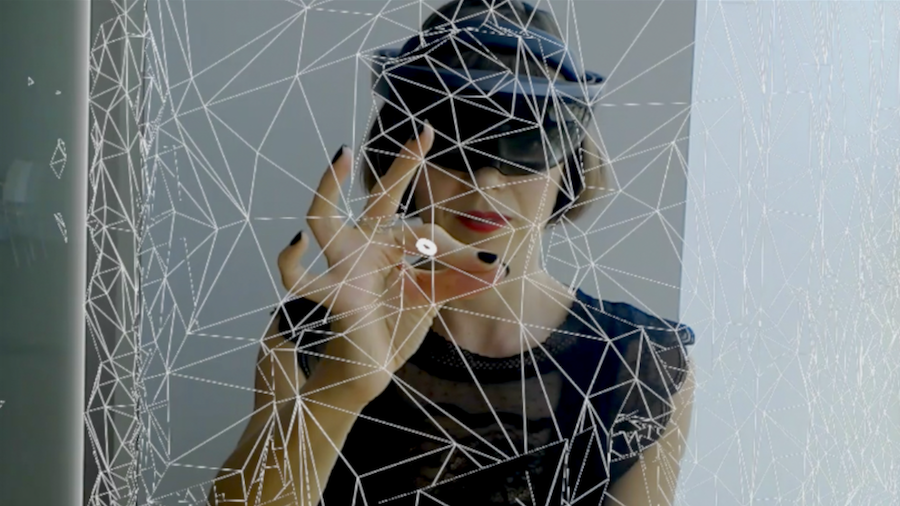

London-based artist Jane Gauntlett will present at 2020 Meeting Place. Image courtesy Jane Gauntlett.

Making this piece has taught me a lot about technology, a great deal about narrative and a great deal about audience care – how to make people feel comfortable. They were putting their trust in me, and I worked very hard to keep that trust. It has had a huge impact on every piece I have made since.

It also taught me about the currency of storytelling, by inviting them into my space and sharing an intimate experience and giving them licence to ask me personal questions and share their own experiences.

In 2015, I discovered virtual reality headsets on Kickstarter. I saw them as an opportunity to test out the concept as a 360 experience. The objectives were still the same.

The concept that I wanted to explore was how to bring other characters into the experience. To share what it was like for me to have an epileptic seizure in a restaurant, where both friends and strangers were present. This piece was called, In My Shoes – Dancing with Myself.

In this [work] audience-members sit in pairs across from each other on small round tables, with white tablecloths. On the tables are clip boards with menus on … Some audience members are having their headsets prepared by a performer dressed as a waiter.

The piece is shot from a first person perspective, my perspective. The details inside the headset match what is in front of the participant on the [theatrical] set. But when the participants look down, they can see my hands resting on the white tablecloth. I am alone and I am waiting for a friend. I’m nervous.

This piece was made from medical conference in Philadelphia, and it was an experiment. It was programmed for international film festivals, art festivals and tech festivals. This was a whirlwind of introduction into the tech industry.

It was challenging for me to accept the way that participants were treated in tech spaces. I regularly had expressions like, ‘You are going to love this’ and ‘You are doing this wrong’. It was challenging the way I was treated.

In 2017, I made a piece called Intimacy. A man and a woman are sitting very close together, in headsets. They are positioned as if they are looking into each other’s eyes. In My Shoes – Intimacy was about the connections we make with strangers, the connections we make with our partners and the connections we make when we first met people. In this case, it is a Tinder date.

It is designed for two participants to experience the piece at the same time. They experience different interactions from two different first person perspectives. It was about the messy, awkward, hurtful, exciting ordinariness of intimacy.

People are tense, nervous and often self-conscious. They cannot see the space around them. Is not like being at a comedy club, where you sit back and have a drink. Sometimes the jokes are inappropriate and you sometimes you need to feel that it is OK to laugh. By seeing and hearing the people around us, we are given permission to do so. This is not possible in VR headsets.

In My Shoes Intimacy taught me a lot about how people behave. What I like most is when people spend time together afterwards.

In 2018, I discovered mixed reality headsets. Mixed reality headsets allow audiences to see both the real world and the virtual world overlaid over the top. Think Pokémon Go but with some futuristic looking spectacles.

I made a piece called True Love. It is a piece about data and it frames the concept that we can introduce audience members to the loves of their life using data. I would approach people and tell them we had collected their data and found the love of their life. It is a bit creepy, really.

I took them to a table and guided them into the headset and told them that their date had gone to the bathroom. The experience started with the audio. The sound of somebody taking a wee, washing their hands, and opening the door. Then they had the person saying, ‘God, no’ as they approached the participant, and they looked quite embarrassed. Their first line was, ‘You heard that, didn’t you? I’m so sorry’.

We use this as a device to shift the power from the performer to the participant. To take away the pressure from the participant and to take away the formality of the headset. The participants were able to see their date through the lenses.

The headset overlays intimate data about their partner over the top. I wanted to see if I could make my audiences fall in love.

Tips from the past 10-years for working with headsets

The 10 years of working on the In My Shoes Project, has taught me a lot. I don’t think I could ever put somebody into another person’s shoes. They just don’t fit. But I know what it is like to share intimate space with audiences and I know what a responsibility that is for the maker.

The five years of working with headsets has taught me a lot. Technology can sometimes be the Emperor’s new clothes. I’m not always a fan of working with headsets … I feel that the headsets are uncomfortable and inaccessible in so many different ways. One of which is that they are very expensive.

Virtual reality and mixed reality headsets are just a platform. I wouldn’t say they are more effective at promoting empathy, intimacy or automation than a theatre piece, painting or conversation at a bus stop.

I have been mentoring artists who, due to the current climate, are keen to explore using digital formats. Questions I ask are, ‘what do you want to see?’, ‘who do you want to see it?’, and ‘why do you want to use headsets?’

What can this technology, platform and space do that other platforms can’t? Not everyone can answer these questions.

Making work using technology is often very expensive. I try to create a mock-up of what I want to make using paper and audio. It is important to work out if I am choosing the right platform at the very beginning, because it saves me a lot of money.

In my career, I have occupied many spaces. Some that I fit into better than others. The space of the artist, or the space of the theatre maker, the space of the storyteller. When I was told that VR would never be a platform that was taken seriously in the art world, and that no way would VR headsets ever be used to promote empathy, this was in 2011.

I think that there is a trend to call things innovative and new and that kind of language. But if we look back through the history of art and platforms and technology, it is not that new concept.

I think as artists, audiences come at the front of our development. I think that most of the work that I’ve seen has been made by huge technology companies. This is basically a good way for me to get into trouble. Often ego can take over, and a feeling of needing to be clever. The feeling of it needing to be the best technology.

It is about the narrative and the overall experience. I think that audience care is about budgeting for it; that there is always somebody there to make sure that audiences are taken care of. That any facilitators or performers are really well-trained. It is something to budget for.

Meeting Place Forum is an annual even presented by peak body Arts Access Australia. It was held online, over two days, 15-16 September 2020.