Street artists may have been welcomed into the mainstream but taggers and writers are maintaining the rage. CDH is among their targets but he can see their point.

‘I’m like a Sid Vicious for a new generation”– Avril Lavigne

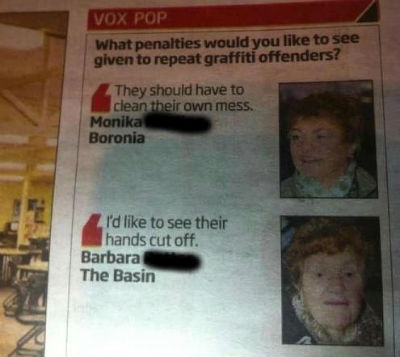

Many people hate graffiti. The awesome vox-pop grandma below is one example of someone who doesn’t like it and doesn’t want to fuck around about it.

For this article, I’m not asking you to like tagging (signature- based graffiti) or call it art, but I am asking for two concessions from the conventional characterisation of graffiti as merely territorial primitivism, like ‘dogs pissing on a wall’:

- Tagging and graffiti are widely practiced subcultures. Many people, particularly disaffected young people, do like it. It does hold meaning for its practitioners.

- Graffiti is an oppositional culture. The average person isn’t meant to understand it or like it. Similar to first wave punk (think of the Sex Pistols in the late 70s) graffiti represents a public rebuke of traditional, hegemonic values.

So you might hate graffiti. But I ask you to also hold the idea that you’re probably meant to hate it and it’s a way for people to define an identity that is individual and separate.

At the turn of the millennia, street art emerged from graffiti culture. The key distinction of street art was that it was an open culture; the average person on the street was meant to understand it. Street art typically used an iconographic vocabulary of mass-media motifs like celebrity faces and retro gaming aesthetics. Its immediate familiarity meant anyone could interpret it.

Since then, there has been an ever widening gap between street art and graffiti; graffiti has remained oppositional while street art has drifted to become the most mainstream contemporary art practice.

Street art is commonly misconceived as a counter-culture but for many street artists, this is no longer true. Take a walk through Melbourne Central- it’s filled with street art. It’s also a shopping mall, whose entire commercial viability is contingent on securing the broadest consumer appeal. I met our conservative Lord Mayor recently; he was gushing with praise for the city’s street art (the zero tolerance policy of the early 2000s is apparently gone), but he, was quick to point out that he still hates those annoying squiggles.

As a non-commercial street artist, I confess I have affection for graffiti culture. Street art is increasingly populated with artists whose ambitions are to secure good gallery representation and win a major art prize, like an Archibald.

In graffiti culture, you meet guys who have been painting for 20+ years, but will never sell a painting, and they know it, and they’re fine with that.

Over time these divergent aspirational goals have caused a schism between the two practices and there’s now a growing tension between them. This rift appears thematically in the work of Lush, who occupies the space between graffiti and street art.

Many writers and taggers express an open hostility to street art and similarly many street artists I know patronize writing culture. This mounting tension was manifested and further exacerbated in late 2012, when taggers Jetso and Pzor systematically capped (disrespectfully defaced) works by prominent street artists[1]. This work of mine was among those they targeted.

Then in early 2013, writers PAA capped street art with slogans like “commodification of culture”, “writers united against street art”, “fuck off- leave it in your studio” and “nothing personal but you are a cultural rapist”.[2]

People in street art weren’t impressed. I’ve heard PAA, Peezer and Jets described as “pathetic toys” (young untalented writers), “jealous teenagers with no talent” [3] and “resentful and begrudging”. There’s a general sense that the capping is fundamentally wrong and motivated solely by envy toward street art’s commercial success.

I think these characterisations are wrong. These are not failed gallery artists; they’re established writers. This projected motivation of jealousy offers a convenient narrative that sidesteps the central issues raised, particularly by PAA. So in part, I am writing this article in defence of them. I’m not trying to encourage the capping but I hope to renew a mutual respect amongst street practices and interrogate the key issues of the events.

Commercial street art heavily trades on the street cred of the outlaw persona that accompanies it, but writing largely paid the price for this credibility. Writers are the ones breaking into train yards and going to prison, while street artists are putting up legal murals or token stencils in back laneways and occasionally having their work buffed.

One writer expressed it to me like this: “I’ve been chased down the street by owners and I’ve been to court multiple times for my art. That’s cost me a lot of time and money. It’s not right that a street artist can come along and say they’re just the same as me. That’s the problem: when someone acts like it’s the same thing.” That’s an important issue because these hardships testify to the authenticity of the writers. It’s provocative rhetoric but in essence some street artists are “cultural rapists” when they appropriate and commodify this cultural capital.

So it’s important to record a truthful history of street practices; to recognise a different lineage and aspirational destinations for graffiti and street art. Graffiti represents the public self-expression of a disenfranchised sub-class; street art (particularly mass-appeal gallery street art) increasingly represents a traditional hegemonic value set.

There’s a common and erroneous narrative that tagging evolves into street art and then street art graduates into gallery art. Pzor and Jetso defiantly declare that tagging is a separate culture, as an end to itself. I empathise with that position because I see street art as its own end, not a gateway to a gallery career. The ‘evolutionary’ narrative is insulting because it establishes a Bourdieuian hierarchy that implicitly sets street practices as primitive and inferior. It also falsely implies that all street practitioners secretly aspire for recognition in the gallery arts.

Thowups, fast, two colour lettering like the piece below by PAA are a case in point: they’re drippy and technically bad by graffiti standards. PAA are capable of significantly better technical pieces, so we should interpret this as intentionally bad graffiti.

Many gallery exhibiting street artists are anxiously self-conscious of their outsider status. The audience demand for street cred encourages artists to posture and blur their backgrounds. There’s a fine line to walk because transitioning into the gallery signals street artists want to work for a broader public.

This sits uncomfortably with the romanticised notion of innately inspired bohemians. To be seen as careerist undermines the street artists’ claim to the post-renaissance ideal of the autonomous artist. Between the implosion of the post-graffiti art market in the mid 80s and the rise of Banksy in the early 2000s, graffiti was merely a way to express oneself.

After Banksy, it became a springboard to a commercial gallery career. Some artists have used the street for a brand construction; a way to signal they’re an authentic artist with street cred. PAA, Peezr and Jetzo publically rebuke this by saying street art isn’t graffiti and it isn’t authentic. The street is being used as an advertising gimmick. They take away its street cred, which requires the art to be judged by its own intrinsic merits. This ultimately demands a higher standard from the artists and so counter-intuitively the capping sprees help to strengthen the street art culture.

Today street art finds itself limited to a shrinking territory. It’s being divorced from graffiti culture. Street art still doesn’t have an art theory and it’s often posited as a folk art, so it has limited recognition within the fine arts. The appeals to a mass audience undermine any claim to an avant-garde practice. Therefore, it’s increasingly left with a notoriously fickle mainstream audience of dilettantes. Street art widely overlaps with hipster culture, so significant portions of its audience are primarily interested in the art for social utility. As this cultural capital is depleted, it becomes ever more important to address real issues, like the notions of authenticity, so the culture can stand without the crux of its street cred.

[1] I have deliberately not named the street artists capped here for 2 reasons. (1) The reaction was against street art culture generally, not the specific artists and (2) Naming them can only causes embarrassment and anxiety for these artists.

[2] PAA focused on a single Melbourne street artist. I think this targeting was misdirected; there are more commercial street artists that are more directly responsible for commoditizing the culture.

[3] In reality Peasor and Jetz both have tagging careers of almost 3 decades, they pre-date the existence of street art by almost 2 decades and are widely considered the most prolific taggers in Melbourne.