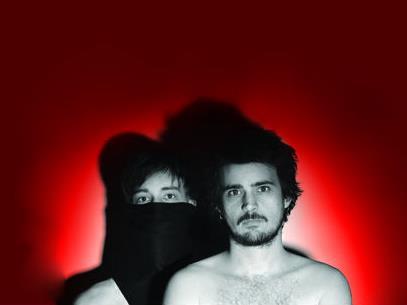

Image: A Sri Lankan Tamil Asylum Seeker’s Story as Performed by Australian Actors Under the Guidance of a Sinhalese Director via Playwrighting Australia

Australian theatre is always being urged to open itself to more diverse stories, reflecting our broad population.

But when playwrights and theatre-makers engage with cultures that are not their own they often run into trouble.

Who has the right to tell these stories and how do you ensure that they don’t become a recipe for cardboard cut-out characters and hackneyed stereotypes about other cultures? Those questions were put under the microscope by a panel at the NSW Writers’ Centre’s Playwriting Festival on March 19.

It’s a process that can go horribly wrong at the production stage as chair of the panel playwright Michele Lee related in her opening remarks. She talked about an aborted attempt to stage the play Jesus in India at Clarion University in the US.

The university was forced to cancel the production after the playwright Lloyd Suh expressed his ‘severe discomfort’ at white actors playing Indian characters in his work. The playwright thought the parts should be re-cast with students of South Asian descent in the roles. But insufficient Asian or Pacific Islander students were interested in playing the roles. The result was that Suh withdrew the rights just days before the production was set to open.

In a letter to the university Suh argued that selecting white actors to portray non-white characters was ‘contributing to an environment of hostility towards people of colour and therefore perpetuating the lack of diversity at Clarion now and in the future’.

Panellist and award-winning Sri Lankan playwright and director Dhananjaya Karunarathne described how he met with fervent opposition when his play about a Sri Lankan asylum seeker was presented by Wollongong’s Merrigong Theatre Company.

The work acknowledged the problem of appropriation in its convoluted title: A Sri Lankan Tamil Asylum Seeker’s Story as Performed by Australian Actors Under the Guidance of a Sinhalese Director.

But even so local Sinhalese people in Wollongong boycotted the play.

‘It was so complicated the whole project,’ he said.

‘They say that I have kind of changed their stories for the Australian audience but they haven’t seen the play.

‘They knew that I would be criticising Sri Lankan Sinhalese…and they got upset when they found I was going to tell their story,’ he said.

So how do you negotiate the tricky path of writing for cultures that are not your own or if you are from the same cultural background how do you tell stories that respect your community?

‘It’s a credibility call with most work,’ said Donna Abela, who founded Powerhouse Youth Theatre in Western Sydney. She has written more than 30 original and adapted plays and works with first-, second-, and third-generation young people.

‘We are literally working with some young people who have arrived from Afghanistan six months ago and we’re working with some people who are third-generation post-war Italian migrant families.’

One of Abela’s most recent credibility calls came when a close friend shared her family story with her and, with her blessing, it became the inspiration for the play Jump For Jordan. Abela, who is not Arab, said she asked herself if she was ‘wog enough’ to write the story.

‘I passed that test. I was wog enough to write that though my credibility – in a very gentle way – was kind of questioned all the way along.’

Abela said something that helps her when she’s considering such questions is to recognise the difference between ‘authenticity and credibility’. ‘I never claim authenticity when I am working with different cultures or writing stories with different cultures that aren’t necessarily from mine. But what I do offer is credibility.’

You also ‘embed it in an integrity of process’, she said. ‘From [my friend’s] story – she bequeathed it to me – then it became mine; the cast were Arabic so an interrogation of culture happened in the room; I had a Jordanian dramaturg at one point,’ she said. ‘So I did my research.’

‘Also my aim was not to pretend to be other than what I am or to be other than the work was – which is a piece of fiction,’ she said.

Jada Alberts, Indigenous actor and writer and current Intersticia writer in residence at Bell Shakespeare, said: ‘I think it has to vary from work to work. I think there has to be no set rules really when approaching protocols and work about the other when you’re not a member of the community of the other.’

‘It’s very easy to generalise,’ she said. ‘I do it about middle-class white men and even middle-class white women when I’m writing and particularly when there are huge social constructs that silence the voices of the people that you’re representing within a character you have to be really careful about every decision you make.’

She thought the words ‘consultation and collaboration’ were over-used, but in practice it requires a playwright to be ‘open and committed to the integrity of the characters being represented’ and having ‘Indigenous key creative people’ involved at every stage of the development and listening so it becomes a ‘respectful exchange’ rather than ‘an appropriation’.

Kylie Coolwell, Indigenous actor and writer of Battle of Waterloo, said she believes Indigenous stories should be told by Indigenous people. ‘There are a lot of stories that are no-go; a lot of things are sacred; and, even me, I can’t write about them at all.’

‘I think a non-Indigenous writer could potentially cross that boundary and because they don’t live in that [Indigenous] community they can.’

But even as an Indigenous writer consultation with community was important. ‘As I was writing [Battle of Waterloo] I would be showing people in the community,’ she said.

They loved the play when they saw it but that doesn’t now give her carte blanche to write whatever she likes. ‘For example, I’m really interested in telling my great-grandmother’s story but obviously I’ve got to now navigate through the family because it’s not just my story.’

The key is respect, said Coolwell. ‘A really good example of that working in Aboriginal storytelling is Louis Nowra’s Radiance. He worked with Rhoda Roberts and I think Rachael Maza to create this story that was really universal and has become part of the canon.’

But it’s also about ‘honouring’, she said. As an actor who has had to play in scenes written by non-Indigenous people she often found they were missing the ‘lightness’ that made it possible for Indigenous people to survive.

‘We wouldn’t have been able to survive if it wasn’t for the laughter and the jokes and the comradeship. I think often when non-Indigenous people are writing – especially about issues such as the stolen generation or about the past and colonization – they make it too depressing.’

Abela said she would be wary of people who just want to do a ‘cultural safari’ to the margins and then come back to the centre. ‘I think you can question your own practice and question other people who want to work with you.’

‘What I see cross-cultural work doing is it doesn’t go to the margins and pluck and pick and appropriate or patronise,’ she said.

To her it is about creating different centres where there is a meeting of cultures or communities. ‘It’s about validating that as the middle, as the common ground and making work from there so that’s shifting power.’