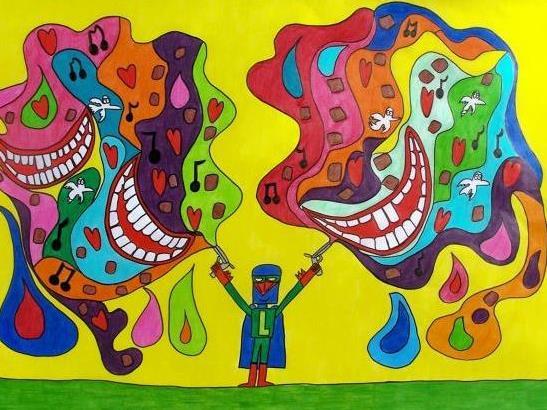

Image, Tim Sharp, Laser Beak Man: A Double Shot of Happiness

In 1993, Judy Sharp was told by a doctor to put her son Tim away and forget about him. The doctor said Tim, who was diagnosed with autism, could never love or communicates.

Speaking at the Brisbane Writers’ Festival recently, Judy Sharp recalled that her ‘heart shattered into pieces ‘at the doctor’s words.

The next four years were a time of anxiety, terror and pain. Tim did not speak and cried constantly. Sometimes the neighbours became so worried by his crying that they called the police

Sharp’s breakthrough was born from desperation. One day Tim was beside himself and she didn’t know what else to do, so she sat down and started drawing. Tim came over and watched, and for the first time all his tension was released. She drew and drew and drew, and when she finished he took her hand and pushed it back towards the pencil.

Drawing changed Tim’s life. After a year of watching his mother, he picked up a pencil and began to communicate through drawing. The more Tim drew, the more his speech developed.

Tim’s story is an example of the power of visual expression to unlock communication for people who find speech an impossible barrier.

The internationally renowned neurologist Oliver Sacks recounted in his book The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat his encounter with a young man who was entirely uncommunicative.

‘Draw this,’ I said, and gave José my pocket watch. He was about 21 and had earlier suffered one of his violent seizures. He took the watch… [and] his distraction, his restlessness, suddenly ceased.

‘He’s an idiot,’ the attendant broke in… ‘He can’t even talk.’ José turned pale…

‘Go on,’ I said. ‘I know you can do it.’

José couldn’t talk but he was not an idiot. Like Tim, he needed other forms of expression, another way to break into his brain.It is a story that Barbara Arrowsmith-Young, sees repeatedly. She is the founder of the Arrowsmith School in Toronto, a program for educating children with disabilities that identifies specific learning disabilities and creates individualised exercises to help them overcome their difficulties.

Arrowsmith-Young created her program after suffering through a childhood battling disabilities. In Grade One she was told she had a ‘mental block’ and imagined a solid wooden block in her brain that stopped her from learning all the things other children her age found easy.

She too encountered the world visually rather than in words. She couldn’t process language; didn’t understand relationships; was uncoordinated, and constantly injured. She had no sensation on the left side of her body; and she got lost all the time. Barbara finished school, but only through what she calls a ‘heroic effort’. Education was terrifying, and school was difficult and lonely.

Her breakthrough came when, at 26, she created a set of exercises to teach herself to tell the time. After literally hundreds of hours repeating her exercises she began to understand language.

Now 64, Arrowsmith has a Master’s degree in School Psychology The Woman Who Changed Her Brain, a book which explores her own and others’ stories of transformation and the extraordinary power of neuroplasticity.

Her belief is that creative education depends on experimentation, exploration and discovery and on harnessing people’s gifts to support deficiencies.

For Tim Sharp, drawing has given him a path to a full life. Now 26, he is the creator of Laser Beak Man, an animated superhero which has been made into a theatre adaptation and an eight-episode animated television series, which has been shown on ABC3. He has exhibited at the Sydney Opera House and National Museum of Australia; appeared on ‘Australian Story’ and was a finalist for the Young Australian of the Year.

Judy Sharp has published her story of Tim’s journey in A Double Shot of Happiness (Allen & Unwin).