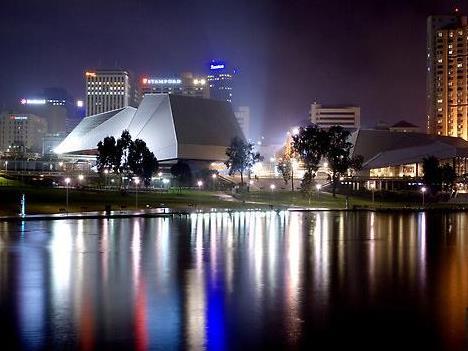

Adelaide Festival Centre, one of the centres used in Caust’s research

In terms of leadership, the director of a large purpose-built performing arts centres centre may be little more than a manager who ensures that the books are balanced; alternatively, the director may be an active producer/entrepreneur who envisions a creative and expansive role for the centre .

In addition, there is often a core tension for the leader between the demands of making art and the practical reality of making ends meet. Centre outcomes may therefore be determined by the leader’s understanding of their role or by the type of individual (and his or her skill base) appointed to the position.

If the leader has a transformational style, he or she usually possesses clarity of vision and the courage to undertake often radical change in the face of opposition from many sides. At the same time, the leader must develop the commitment and trust of the staff to support the change and build the capacity in them to work together to achieve it. For example, it has been noted that contemporary creativity models depend on collaboration rather than competition.

As Byrnes notes, in the context of a complex arts environment such as a performing arts centre, “… a leader with great skill as a transformational leader and negotiator will be required”. Many arts contexts, particularly more contemporary examples, demonstrate a leadership model or organizational structure where leadership may be shared or distributed and is located around a more collaborative model than a conventional hierarchy. The positional leader may then involve everyone in owning the process, where he or she demonstrates superior communication skills and possesses the capacity to work successfully with many different kinds of people.

Leaders must have the skills necessary to persuade those around them to accept and support a shared vision; the leader must also have the ability to encourage his or her followers to work collaboratively towards the realization of the vision. In addition, the leader must be able to share the leadership spotlight and allow others to take the leadership role when required. This requires a trusting, respectful, environment which is focused on achieving the outcomes for the arts centre rather than focusing on the ego needs of an individual leader.

…

The role a performing arts centre plays within its community is a key issue when selecting an appropriate leadership model for it. Certainly, the building of such a centre by a city, State, national government or even private benefactor is usually an assertion of a local identity. The very existence of such a centre in a city could be viewed as locating that city on the cultural, political and economic map. A city may not be viewed as significant unless it has a large performing arts centre for proud display to visitors. This centre, therefore, encapsulates the notion that the possession of a major cultural edifice gives its city higher status, value and power. Florida notes that when people make choices about where they want to live, “… the economic and lifestyle considerations both matter, and so does the mix”. The benefits of providing a healthy economic environment may not be enough to attract labor (especially skilled) and even investment; lifestyle benefits in a location are equally important. Recognizing that a city will benefit from the provision of good cultural facilities makes good economic sense. If the aim of the centre is to assert the power and status of the city, then it must also demonstrate the city or nation’s highest artistic and cultural achievements and/or provide a place for the display of the high arts from other countries from around the world. Thus the existence of the centre and the kind of spaces it houses provide both a home for the “high” and/or “best” art as well as a place for the “élite cognoscenti” to attend and be seen. The relationship, therefore, between the centre and its home is complicated. It is both a cultural centre and a status symbol. It is of cultural significance but also of economic and political importance.

Another dimension is the relationship the centre has with local artists. Does the centre embrace local arts activity or does it exclude it from the centre? Many arts practitioners may view the prospect of the establishment of a performing arts centre in their city or town with pleasure and approval, and consider it to be an acknowledgement of the value of the arts in their community. However, the concept of a performing arts centre is likely to be more complicated than this; there is no guarantee that, in addition to its role as a presenter of work, such a centre will be an actual producer of “art” as such, nor will it necessarily embrace local arts activity. The focus of the leadership may be about producing popular entertainment that guarantees the seats are filled. Furthermore, the costs of the centre, including the initial building and its ongoing maintenance are likely to be extremely high, consuming funds that could otherwise be directed to arts practice or other community undertakings. The very large capital investment made by the State or city in the building also implies a long-term obligation or responsibility to the patrons who funded its construction.

A close association between a cultural centre and its political masters can be problematic for those responsible for the cultural centre. Arts-making involves risk. Any arts activity, even if it is commercial musical theatre, involves risk. The size of this risk can vary, but, because of its very public face, it is always a source of embarrassment if it fails. Taste is fickle and culturally located. Something that is successful in one place may be a failure in another. Whether a centre chooses to be entrepreneurial in its approach or is merely a venue for hire, some degree of risk is involved. This risk is exacerbated when the centre is entrepreneurial and sees its role as a cultural incubator as well as a venue.

An interesting question here is how does the leader of such a performing arts centre manage this risk and choose a path that ensures the success of the centre, both artistically and financially? Michael Kaiser, who is the President of the Kennedy Arts Centre in Washington, believes that, “It all starts and ends with a focus on programming. There is no reason for an arts organization to exist unless it does important programming” When Kaiser took up his position of Executive Director of the Royal Opera House in 1998, he was confronted by a multiple array of compounding issues, including a very expensive rebuilding program, complex governance, constant media attention, political pressure and an arts centre designed to serve several masters. This scenario was compounded by the British media, which took a close interest in the Royal Opera House and interpreted every problem as an outcome of incompetent administration. Moreover, because the Royal Opera House occupied such a significant position in the cultural and social life of the nation, everyone, from the Queen to the Prime Minister, to a teacher at a local comprehensive school, had a view about the centre’s role and the activities that should be taking place there.

The reality of managing large arts centres with direct connections with the government of the day demonstrates that art and politics are irrevocably interconnected. Boards and committees may be peopled by the most powerful individuals in the city or country and need to be managed and persuaded to follow a pathway sometimes not necessarily amenable to them. This could be a particularly challenging task if, in the case of board members, their own money as donors is also involved.

…

Leadership of arts centres is not a simple task. There are conflicting forces, a high degree of public exposure and many expectations embedded in the fabric of an arts centre within any community. The higher profile of the centres intensifies these pressures. So the leaders must be passionate and pragmatic; strong as leaders but able to delegate and also allow others to lead. The challenges implicit in adopting a creative, entrepreneurial approach to the role is considerable.

The leader of a large performing arts centre must be clear and determined in his or her vision for it to prevail; at the same time, the leader must be a skilled and sophisticated negotiator in order to accommodate many different stakeholders. In addition, making a centre a hub of artistic creative activity has risks attached that can impact on the audience, the governance and ultimately the leadership of the centre. Financial imperatives hang over arts centres given their size, complexity and community expectations.

Nevertheless, performing arts centres can be more than an edifice for the performing arts that every city needs. They can also be a centre for making or enabling exciting arts practice. While large performing arts centres began as a structural model in the West, they have now been embraced in many countries in the Asia Pacific region. It would seem that the challenges embedded in leading these centres are similar in different cultural contexts. The organizational model and cultural expectations of the leaders may differ slightly but, overall, the expectations in the role are similar.

This article is an edited extract from Arts and Cultural Leadership in Asia edited by Josephine Caust and published by Routledge.