What does it mean to be a poet in a world where poetry is seen both as a concern and a calling, a prayer and a practice? Three accomplished Australian poets around Australia show how poetry fits in alongside, but also gives rise to, other tasks. There are the tasks of ‘filing to work, this poem a fishbone in my briefcase’, as the Irish poet Nick Laird would have it, but also the task of reconciling society’s wounds, whether racial or cultural, or devoting oneself to the art of love.

These three poets vary in age, gender and ethnicity, but have in common the devotion to a form of soulful engineering that consoles as well as constructs. ArtsHub speaks with them separately, but together their comments form a conversation about a strange profession where the works talk to each other as well as to the writers themselves. They are compelling figures and have urgent ideas about what it means to be in the world now.

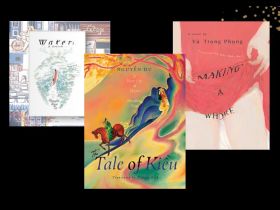

Nam Le came to Australia as a refugee and wrote a short story collection, The Boat, comprising diverse tales, ranging from the experiences of his Vietnamese refugee father, to a New York painter with hemorrhoids – and myriad other stories in between. The short story collection was unusual for its polyphonic range and won the 2009 Australian Prime Minister’s Literary Award, the Melbourne Prize for Literature, the PEN/Malamud award and the Dylan Thomas Prize. Le has just released a collection of poetry entitled 36 Ways of Writing A Vietnamese Poem. So how does writing in one format inform the experience of another?

‘It’s strange, the more I write (and I mean “write” and not “publish”) the more it becomes clear to me that all the work is all one work. Looking back, I don’t think I could have written any of my stories as poems (or essays), or vice versa, but probably that’s a dumb thing to say because a thing isn’t separate from its form; some would argue that it’s nothing but,’ he says.

‘So then the question becomes: is there a moment or stage, before the thing takes form, when all forms – poem, story etc – are open to it? And what role, if any, do I play in seeing this stem cell to its specific expression? If that moment or stage exists, though, to connect it to any eventual outcome seems to me to dishonour it. Things take shape delicately, from and in every way imaginable – through sound or language, idea, memory, feeling, story, incident, epiphany and figure. Who’s to know what’s growing in the dark until it’s committed to light and fault?’

The notion of a creative stem cell that can take any form is a vivid image, and expresses the versatility of poetry, as well as its creative potential. But a poem can also be a lens or a way of seeing, a built environment, or anything besides.

This is clear to Jazz Money, the Indigenous author of How To Make A Basket. Money has received the David Unaipon Award, the Aunty Kerry Reed-Gilbert poetry prize, the University of Canberra Aboriginal and Torres Straight Islander Poetry Prize, a Copyright Agency First Nations Fellowship and a First Nations Emerging Career award from the Australia Council for the Arts (now Creative Australia). In addition to writing, Money trained as a filmmaker and cites visual thinking as an area that informs her expression. But how do the techniques of poetry specifically allow someone to think about the world in new ways?

‘Poetry pairs images and meaning in ways that enhance, contradict or complicate our previous understandings. It’s the revealing of new information in a place where you felt comfortable that helps me understand the complicated layers of meaning and perspective in our lives.

In particular, I’m fascinated by the ways that people from marginalised communities seem to flourish in the poetic form. Challenging the structures of language feels like an extension of challenging the structures that inform our society. Poetry can enable us to imagine the world in radical new ways, but it can also remind us of our shared needs and shared wonder.’

The shared wonder of poetry as a tool for self-expression and as a form of listening is especially relevant to Thuy On, ArtsHub‘s Reviews and Literary Editor, who has also written two poetry collections, Turbulence (2020) and Decadence (2022). The first was shortlisted for the Mary Gilmore Award, the second longlisted for the Stella Prize, and a third collection, titled Essence, will see the poet once again published by University of Western Australia Publishing (UWAP) in 2025.

For On, poetry is a vocation that represents freedom, experimentation and choice. When asked why poetry inspires the love of its readers, On replies, ‘Because the very best poetry, or at least the poetry that resonates best with me, is the kind that acts like a distillation of the truth, a burning down of emotion to its essence. Sometimes you don’t need to read a whole chapter in prose. A poem can say the same thing with less preamble and extraneity, because it gets to the nub of the matter. Its succinctness is its ultimate power.’

For Money, poetry is a form that points the way to the future. ‘Poetry is a very flexible form. The rules often seem esoteric but, truthfully, there are no rules, which makes the space very generous. It can also be an incredibly efficient way to communicate – there are poems that communicate more meaning and emotion in a single stanza than some novels accomplish in 100 pages. We all know that feeling when poetry – whether it be graffiti in an underpass, an obscure song lyric or lines from a canonised poet – reaches right in between your ribcage to unlock something deep within you, when suddenly you reverberate with the sense of being understood.

‘I think that’s why people constantly return to poetry, and why poetry endures through the ages. Poetry at its core is an oral tradition and the human desire for connection relies so often on language. It’s the way we mark significance, and the way we transmit through to the future.’

Interestingly, Le argues that readers of poetry aren’t necessarily enamoured of the forms they follow. ‘I think a lot of readers and poets are disillusioned with a lot of poetry. And for good reason. But good poetry goes deep: it opens up the limbic intensities of music while accessing the cortical levels of language. It becomes the reader.’

Read: Spoken word poetry: screaming their truths

These three poets show how one of our most ancient art forms is also a form of transfiguration, and a way of becoming. They show how taking a deep dive into an individual poem is like being in a new element, and how this reflects back to our most elemental, old and basic forms, reinvented for the sophistication of the digital age, and the celebration at literary festivals.

Jazz Money is a guest curator at the Sydney Writers’ Festival, which runs 20-26 May. She will open the Festival with a performance of her poetry and be featured in a number of events.

Nam Le will appear at the Sydney Writers’ Festival on 24 May to present a session on 36 Ways of Writing A Vietnamese Poem.

Thuy On’s third book of poetry Essence will be published by UWAP in early 2025.