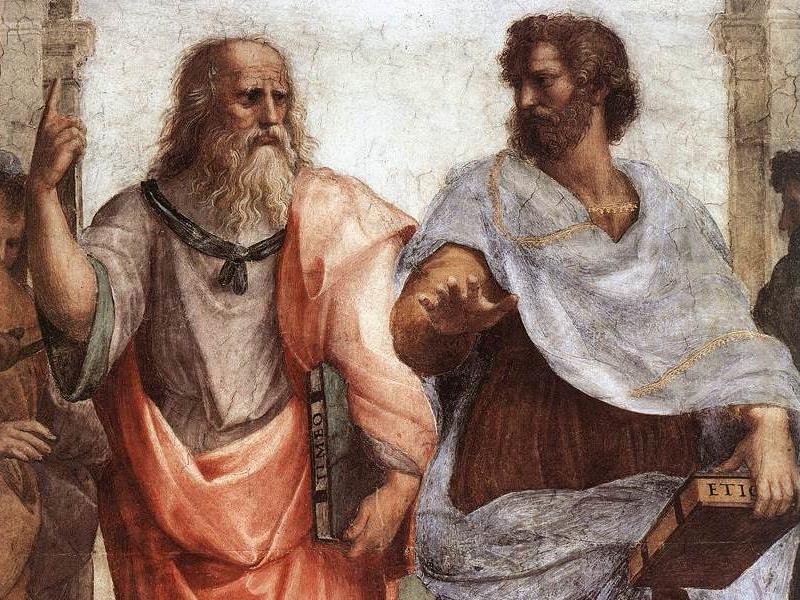

The School of Athens, Raphael. Image: www.wikipedia.org

The Lincoln Center in New York recently received a $100 million donation to renovate its concert hall, a chunk of the $500 million it hopes to raise for the project.

What if the patrons, instead of giving this money to the arts, were to use the money to restore sight to, say, five million people?

This is the hypothetical with which philosopher Professor Peter Singer challenged the audience at the Melbourne Writers Festival’sethics debate, Is Funding The Arts Doing Good?

The greatest good for the greatest number

Aruging from the philosophical position of utilitarianism – that ethical behaviour is doing the greatest good for the greatest number – Singer said that the benefit to the concertgoer could not within the realms of reason outweigh the benefit that restoring sight would have on an individual’s life.

Doing the most effective good, according to Singer, requires channelling philanthropy to charities working in developing countries to combat preventable effects of extreme poverty such as stemming premature death from preventable diseases, or improving life quality by restoring sight or preventing the loss of it, for example. Such practices are cost effective, contends Singer, and therefore not only utilitarian in benefit but a practical in the application of resources, a value that the arts cannot match in results.

Singer addressed the MWF audience directly, saying that as members of an affluent society and individuals with ‘funds in excess of our basic needs’, we are obliged to consider where our resources might best be directed.

‘I’m not arguing that funding for the arts does no good, but rather funding for the arts is not the most good you can do with your philanthropic donations. A comparative claim, not an absolute claim.’

Elaborating on ideas published in his most recent book ‘The Most Good You Can Do: How Effective Altruism Is Changing Ideas About Living Ethically’, Singer stressed the necessity of donations on a ‘needs’ basis stems from the principles of effective altruism, a movement and philosophical grounding that seeks to ascertain how limited resources can be used to have the greatest positive effect on the largest possible number of people.

Kindness by numbers

Artist and artistic director Robyn Archer challenged Singer’s starting point, arguing that the overwhelming focus on larger institutions such as the Lincoln Center misrepresented the nature of the contribution arts makes to society.

Large performing arts centres and major companies are ‘only one small sphere of the arts, albeit the best heeled bit’, she said.

She admitted ‘a certain amount of sympathy for the idea that the enormous sums on ever-more collecting by major museums could be curbed in the interests of alleviating of poverty’ but argued philanthropy was necessary for a range of cultural outcomes.

‘Without philanthropy, much art, both art of the accomplished, rarefied kind and art which a has a social or political agenda would disappear,’ Archer warned.

She directed attention to the empowering good of local arts projects, such as theatre company Somebody’s Daughter, which helps women prisoners during and after their incarceration. She also cited the multiple good effects in the work of arts and social change company Big hArt, which uses the arts to counter substance abuse, help families suffering hardship in drought-ravaged areas, rehabilitate prisoners and bring opportunities to Indigenous Australians.

This kind of philanthropic support of the arts is doing a power of good, maintained Archer.

‘As much as I’m persuaded by Peter’s arguments and the compelling nature of his writing, I just can’t seem to play a numbers game and decide that this kind of philanthropy must be stopped. Kindness by numbers is somehow not working for me,’ she explained.

CEO of Glenorchy Art and Sculpture Park (GASP) Pippa Dickson (GASP) works within a community suffering significant disadvantage She observed the potential for art to act as a tool of social cohesion, to inspire curiosity and to foster learning.

‘It is not a community that anyone would expect to have an affinity for culture except that they have had the advantage of seeing what meaningful investment in the arts can achieve. There might well be more effective ways of giving and making significant social change. I’m not saying that we shouldn’t use tools of arithmetic and reason to evaluate the impacts we have however I’m saying that it should not be the decision making process but merely part of it.’

Frill or fabric

Both Archer and Dickson acknowledged the increasing pressure faced by the arts to justify their worth to society and maintained the necessity of philanthropy in ensuring that the arts survive in the current economic, and even cultural, climate.

‘Artists these days are considered as what I always say ‘frills on the frock of life, instead of the very fabric with which it is woven… the reason there is subsidy of the arts and philanthropy for the arts is because art doesn’t necessarily survive in this society where artists are not regarded as essential service. If we were respected as essential as doctors, nurses, garbage collectors and policemen then we wouldn’t have to go on justifying ourselves in this society,’ said Archer.

Singer reiterated that he was not denying the value of the arts just arguing funding could be better directed. ‘I accept what Robin or Pippa said about artistic spirit. I don’t believe that that would disappear if you stopped funding.”

In a dramatic close to her defence of the arts, Archer drew directly on the power of the arts with a rendition of Bertold Brecht’s wry social commentary ‘What Keeps Mankind Alive?’ She suggested the poet might express the complexities of human nature ‘more effectively than the philosopher and statistician himself’ an illustration of the enduring role of the arts to disrupt and expose society to itself.