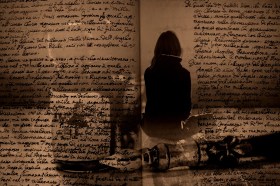

If Eric Charles hadn’t had to leave his native Cameroon to be humanly trafficked (via Malta) to Russia – before finishing up as an asylum seeker in Wales – he may never have understood the meaning of dislocation. Perhaps it’s also a safe bet that without the experience, and the trauma associated with it, Charles may not have come to appreciate the role of writing in catharsis: he now knows it better than most.

‘Because of the way I travelled to Wales,’ comments Charles over the Thursday morning noise of his nineteen-month-old daughter, ‘the best way for me to appreciate it is by writing. While I was back [in Cameroon], I never paid that much attention to [writing] but since my work has been published in Wales, there’s been no going backwards.’

Charles is a refugee writer based in Wales. His poetry, written in English, French and Russian, has been published in those languages and translated into Welsh, and he has worked with the Cardiff University School of Journalism, teaching students about the way he uses writing to appreciate life’s challenges.

It is a subject on which Charles’ friend, writer Tom Cheesman, will speak at an upcoming annual conference held by Academi – Wales’ national society for writers and literature. Entitled ‘In Extremis’, the 2003 conference aims to explore the ways in which writing can contribute to the healing process for people who have lived through a traumatic experience, and features a number of speakers from the country’s literary community.

‘There are two aspects to this idea of using writing as therapy,’ comments Cheesman, with reference to his own work in refugee communities within Wales and internationally. ‘There is the therapeutic value of cultural expression for the individuals concerned, as a way of dealing with their trauma and for dealing with the experiences that they are going through. And there is the communicative dimension – reaching an audience of local people and helping them to understand.’

They are points on which Charles wholeheartedly agrees. ‘When I first came to Britain, my approach was to forget about what happened [to me],’ he says. ‘I left Cameroon in 1997, and by the time I arrived in Britain, in 1999, I just wanted to come here and settle down… but [the experience] cut me up, you see, and I started getting depressed, thinking about various memories… Then I decided to start writing them. I exorcised myself of ghosts.’

Charles says also that the ‘communicative’ element of writing – and of taking his writing to schools and institutions – was a contributor to his recovery from the experience. ‘I found that cathartic,’ he comments. ‘Engaging with people, and not having to shy away, was cathartic.’

While there exists in Wales a number of publications produced by the country’s Somali and Chinese communities, Cheesman points out that the social and cultural opportunities for asylum seekers in the country are few. Those that do exist find the effort of attracting asylum seekers to their programs challenging, to say the least.

‘We have very little infrastructure for refugees – at the level of social services, and at the level of cultural agencies – compared with England,’ he says. ‘Among the people who’ve been here longer you’ll find some who are creative in various ways… But things like classes, whether it be writing or other kinds of creative expression, are not successful. Very few asylum seekers either want to or are able to attend regular sessions – they are living in suspended animation – and, of course, there is also a language barrier when offering creative writing.’

Charles says that the issue of language, and the struggle to adopt the languages of different cultures is one which he attempts to address through his poetry. ‘I write about “adaptation”,’ he says. ‘English is not my first language, but I studied it all through school, and I was also under obligation to study French. I also come from a place where, if you travel eight kilometres, you meet a completely different tribe with a different language, and, because of my experience, I speak Russian and I learnt Armenian… Over here, generally, people speak English. Not so much need for adaptation.’

Where ‘adaptation’ is unnecessary, however, change can be sometimes slow to occur. This has been a frustration experienced by Cheesman, over the last several years of his campaign to have Wales join the Salman Rushdie-founded International Parliament of Writers.

Created in 1993, the IPW, which has connections to the Academi, is a global network which exists to support persecuted writers in a number of countries and regions from around the world. At this stage, according to Cheesman, no government in the British Isles is a member, despite the City of Swansea’s promise, in 1995, that it would join the network.

‘The real reason I have been invited to speak at “In Extremis”,’ he comments ‘is because of my connection to the IPW network. I have been campaigning since 1995 to have the City of Swansea and the City of Cardiff – if not the whole of Wales – join the IPW, and yet it still hasn’t happened.’

Aside from the obvious benefits that Wales’ participation in the network would have on the world’s persecuted artists, Cheesman also feels that such participation would assist in the provision of cultural and educational projects involving other exiles, such as asylum seekers and refugees.

‘I can’t say that there is a centre for creative activity by asylum seekers or refugees anywhere [in Wales],’ he comments. ‘But people are interested, and we will continue to campaign.’

In regard to his own activism, poet Eric Charles has taken a different approach. ‘I’m active in my own little way,’ he remarks. ‘I’m waiting for my autobiographic text to be published, and [through] that, I can counter a lot of issues. I view myself as the voice of the voiceless. I’m taking a small approach.’

‘In Extremis’ runs February 28 – March 2 at the Esplanade Hotel in Llandudno. For more information, visit: www.academi.org