So, you’ve published a book or two and sales are fair to middling, but Australia is a small country in terms of readership potential. Imagine your book reaching a wider network of readers by being recast into a non-English tongue.

ArtsHub reached out to some industry professionals, as well as a number of writers who’ve had their works adapted in different languages to try and demystify the process and vagaries of book translation.

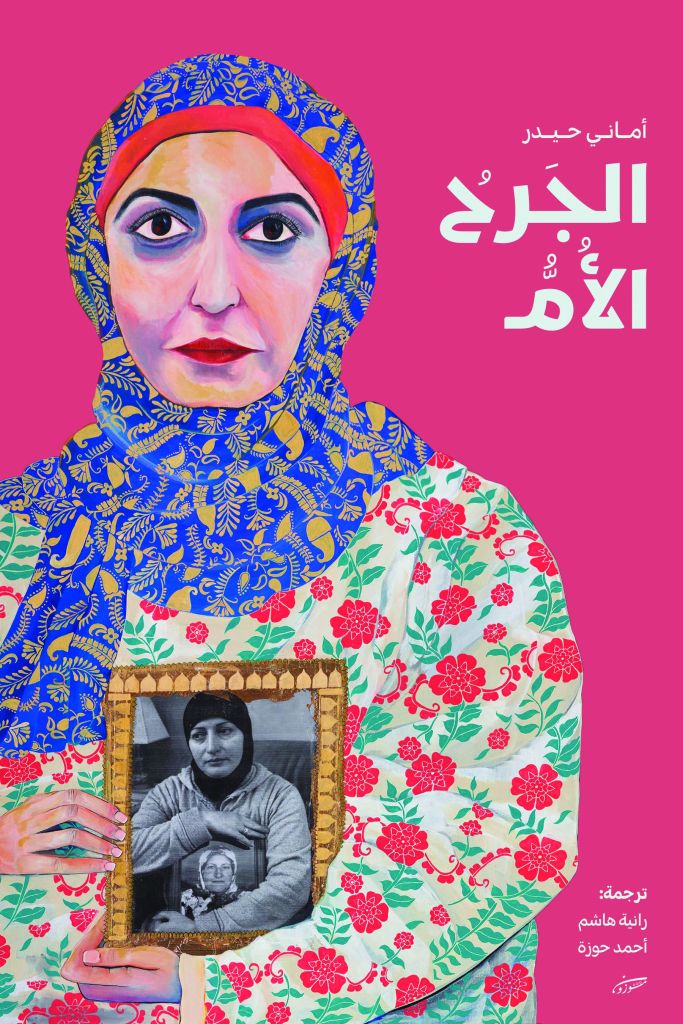

Amani Haydar’s The Mother Wound has been translated into Arabic by a boutique publishing house named Mauzoun in Saudi Arabia, which got in touch through her UK agent. Mauzoun has writers and editors across the Arab world, including Beirut, Cairo, Kuwait, Riyadh and Jeddah, says Haydar. ‘The story is an international one because it deals with migration and war, and the gendered impacts of these things, so it has always been my hope that it be able to reach audiences in my parents’ homeland and the Arabic-speaking diaspora around the world. I had hoped that some day the work would be accessible to an Arabic-speaking audience both here and abroad.

‘It feels especially important to me because we know that migrant women are at an increased risk of domestic violence and face additional barriers in the healing and recovery process because of a lack of access to in-language services and supports. I wanted the book to be able to be used as a resource in my community and for it to reach my mum’s generation.

‘For many people in that group, language remains a barrier. I have friends who have indicated that they want to buy the Arabic version for their mum or dad or other relative, and that tells me there is a demand for literature on these topics in local bilingual communities.’

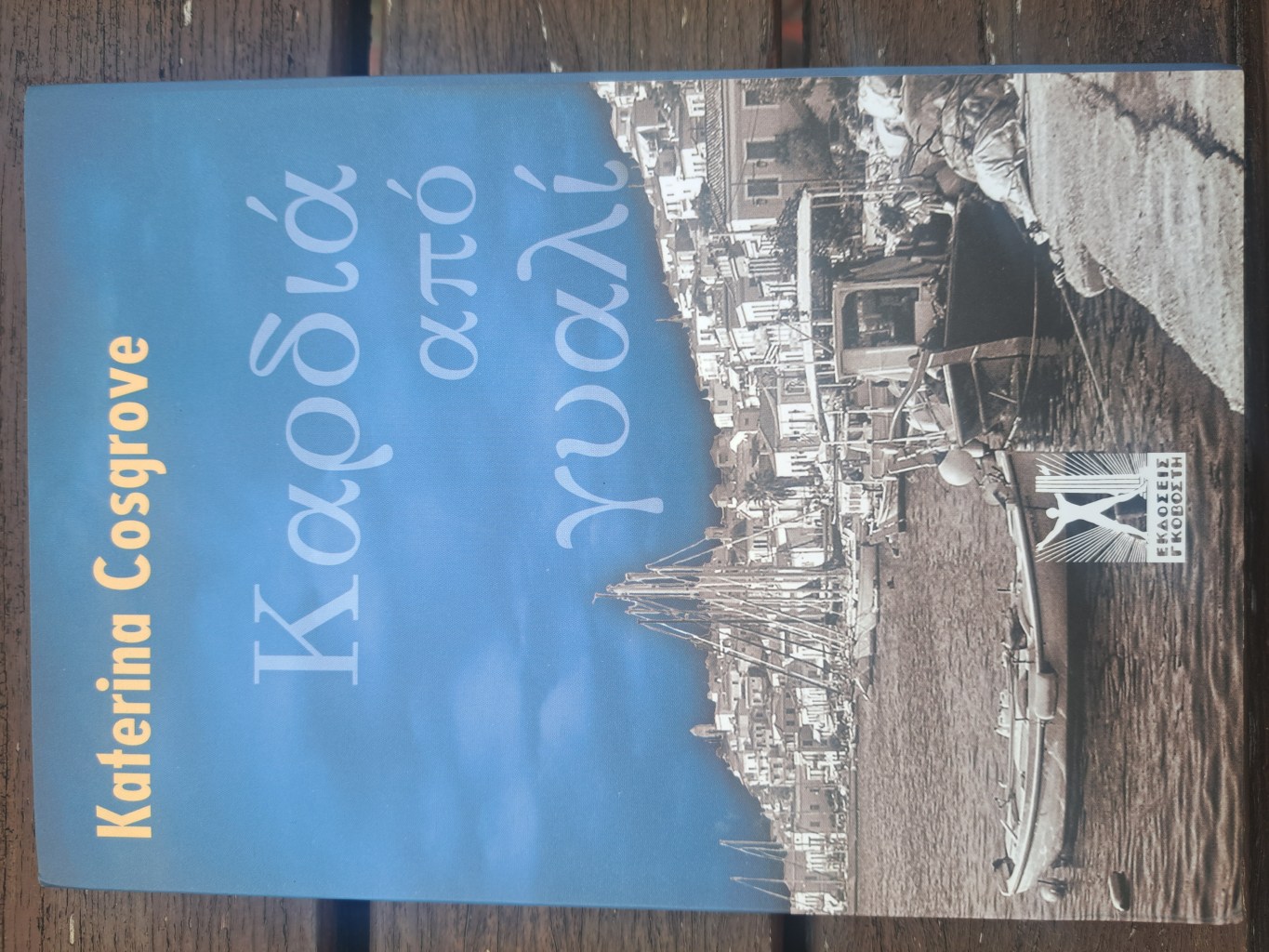

Two of Katerina Cosgrove’s novels were translated into Greek: The Glass Heart in 2002 (published in English by HarperCollins, 2000) and Bone Ash Sky in 2017 (published by Hardie Grant, 2013). Cosgrove’s publisher was Govostis, the oldest publishing house in Greece, established in 1926. ‘[It is] also in the process of translating my prize-winning novella, Zorba the Buddha, published by Spineless Wonders in 2021,’ she tells ArtsHub.

‘My literary agent at the time, Tim Curnow, sold the Greek rights to Govostis and embarked on the task of translating the books, which took a number of years. It was a real labour of love for them, as Greece was not in the best state due to the economic crisis, and the Greek publishing industry was struggling. They truly believed in my work and knew there was a market for my books in the Greek-speaking world.’

The theme of a book can lend itself to a particular translation. After all, if you are writing about a certain country, does it not make sense for the book to be available in said country’s language? In Thoughts on Translating After Darkness, Christine Piper shares the convoluted manner in which her debut novel was transcribed into Japanese. It’s a book about ‘the continued silence surrounding both the internment of Japanese civilians in Australia during the 1940s and the atrocities committed in East Asia by Dr Ishii Shirō, the leader of Unit 731′.

‘In essence, I was fascinated by how an essentially good person such as [the novel’s protagonist] Doctor Ibaraki had the capacity to facilitate acts of evil,’ Piper writes.

‘The day my agent called and told me that Honey Blood was going to be translated into German I was gobsmacked, ecstatic and it felt rather surreal,’ says Kirsty Everett about her memoir. However, for Everett, a proud Darug woman currently residing on Dharawal country, to have her book translated into a First Nations language would be ideal. ‘We’re working on it,’ she says. ‘The songlines of my ancestors are usually working double-time to help with all things book-related for me. I know it will happen when my Darug ancestors feel the time is right.’

Some authors, like Hazel Edwards, are fortunate to see their books transformed into multiple languages. So far the tally is around 10 she says, and range across adult and kids’ books, and includes Finnish, Japanese, Chinese, Tamil, Russian, Polish, Vietnamese and Korean.

Speaking of a different kind of translation, Edwards also has Braille copies that are free to Vision Australia. ‘I’ve always supported them, especially those picture books in the Feelix [Children’s Library] project for pre-schoolers,’ she says.

What kind of linguistic quirks and compromises were encountered during the translating process?

Many of the writers ArtsHub canvassed had to simply trust that their words were faithfully translated because they were, for the most cases, monolingual or at least not fluent in any other languages.

‘While I can read and write Arabic, my Arabic is not of a standard that allows me to assess the quality of the translation,’ says Haydar. ‘This means trusting the professionals on the other end to interpret my work in a way that is true to its intent and to convey the nuances associated with key themes like domestic violence, the Australian legal system and the Arab-Australian experience.’

Sophie Masson has had a dozen of her works (novels and picture books in different genres) translated into various languages. So far they include German, Italian, Indonesian, Thai, Chinese and Korean. Only one them, Three Wishes, under her pen name of Isabelle Merlin, has been translated into French, her mother tongue.

She says, ‘Both the French and German translations indicated in the title pages that the book had been translated from Australian English, which is interesting: when it comes to translations from English, both clearly seem to like specifying which corner of the anglophone world the book has come from!’

‘The translations of both my novels were true to the spirit or the essence of my English prose, as opposed to a word by word literal translation,’ Cosgrove tells ArtsHub. ‘The publisher, Costas Govostis, was very transparent throughout the entire process, asking me relevant questions along the way, checking the use of certain words and phrases,’ says Cosgrove. ‘We did come across some untranslatable concepts (i.e. colloquial Australianisms), but the translators worked around them. What impressed me was the way they lived and breathed my books for years, engaging with them on a deep and immersive level.’

The process of translation

For newbie authors who are simply thrilled to be published in the one language, the idea of their work reaching an entirely different audience is an exciting but foggy potentiality. ArtsHub asked Masson to unpack the process a little.

‘Translation rights [can be] included in the original publishing contract, in which case the originating publisher’s rights manager is the one selling the rights to overseas publishers. The rights managers have strong links with overseas publishers and will approach them online or in person about books they feel could work for their markets. And the rights managers also go to book fairs, like Bologna, Frankfurt, London etc, and present the books to rights managers from the overseas publishers there, and follow up later, and if the overseas publishers express interest and make an offer for the book, then it’s up to that acquiring publisher to get the book translated and by whom,’ she says.

‘As the author, you don’t get involved in any of that, but you’ll be informed when a publisher has made an offer for a certain translation right, and you will be asked for your approval. You don’t, however, get sent the translation to check, as of course you may have no expertise in that language – and even if you do, like me in French, it just isn’t done. It makes the process too expensive and lengthy. If translation rights are kept back by the author via their agent and the agent’s internationally-focused associates, then it’s basically the same process.

‘It’s important to note here that the originating publisher can’t control in which language the books are published: it’s the foreign publishers who decide if the book feels right for their market. The publisher’s and agent’s rights managers simply present the books to as many translation markets as they can.’

What exactly are international rights?

There are, indeed, various ways in which a book can make its way overseas. Nerrilee Weir, the director of Bold Type Agency, a rights agency representing Australian literary agents and small publishers in international markets and in book-to-screen adaptations, further elaborates on how your book can have its own passport: ‘International rights can be sold by a number of parties. The publisher might hold the international rights, or the literary agent, or the publisher and agent might work via yet another third party such as a US- or UK-based literary agent, the network of translation co-agents, or via something like our Australia-based Bold Type Agency.

‘The process remains the same though – the rights seller pitches the manuscript in all markets outside of ANZ trying to find an editor who feels passionate about this work and who wants to translate into their home language and open up an entirely new readership for that Australian author. It’s not just finding new readers though, rights deals are done on the basis of an advance and royalties earning additional income for authors and creators.’

‘Carrying a baby across a river’ – a translator’s perspective

An author herself whose latest book is Call me Marlowe, Catherine de Saint Phalle has translated Australian and US books into French, and French books into Australian English.

‘The feeling is like carrying a baby across a river. The baby is the meaning, the spirit of the text, its essence. The baby must be kept alive, dry and whole. The translator has to get wet and grapple with the river, but once he or she gets the text to the other side – the feeling of having saved it is exhilarating,’ de Saint Phalle says.

‘Translating is all about a voice. If you hear a writer’s voice, then you’re shod and hosed and can set off immediately on your translating trip. Because it is a trip in another man or woman’s boat… Asking a writer to translate is more of a risk. They don’t always “hear” the voice but, when they do, a timeless piece of writing can be the result, as if two poets (the writer and the translator) were working together – two hands joined in prayer. ‘

Advice for those investigating the process of having their book translated into another language?

‘Having agents can help demystify the process. Think about how you will launch translated versions locally and whether you can harness local in-language media. Be prepared to relinquish some control over the final product and how it is marketed. The people you work with will likely know a lot more about what resonates with their local audiences than you will,’ advises Haydar.

Cosgrove suggests that writers ought not be precious with their words, ‘to see the translated works as entirely new expressions, embedded as they are in a particular culture and a different way of seeing and expressing’.

As with anything in the publishing industry, forging and nurturing professional friendships and alliances is crucial. As Everett stresses, ‘The only advice I have is that connections, songlines in my case, are extremely important in this very tough industry.’

Edwards simply recommends that the lucky ones, ‘Enjoy, it is a great compliment that your book travels into other cultures.’