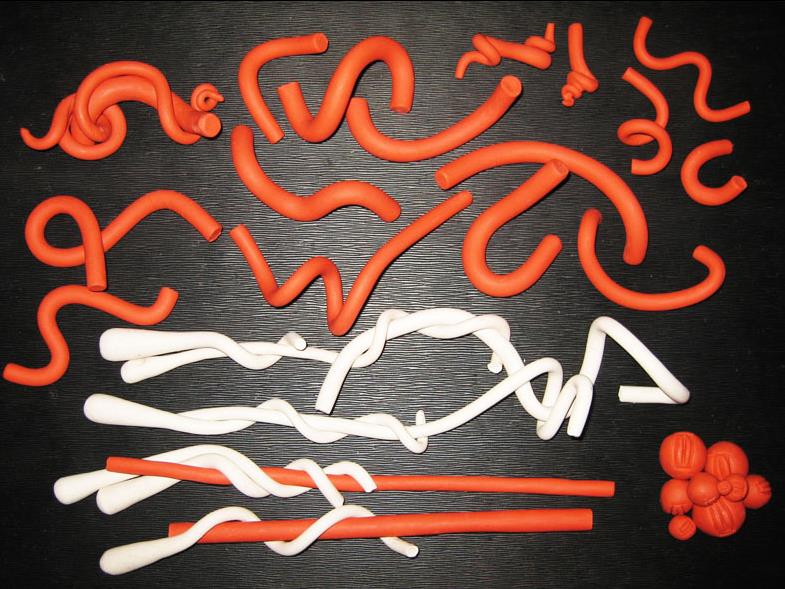

Image Sarah Harvie via Solid Air Designs

In 2009 artist Sarah Harvie lost her husband; six months later her father died; and three months after that her father-in-law had a heart attack an.

It was a series of shocks that made her disregard all of the things that she usually saw as constraints: money, time and resources and really seize the opportunity to explore and experiment in her life and her art.

‘I’d read Naomi Klein’s The Shock Doctrine and in that she describes how Milton Friedman and politicians – Margaret Thatcher, Reagan – used this idea that there’s a period of time – about six months – after a disaster or a shock that sends people into a sense of panic and in that time you can implement change,’ she says.

‘That’s what struck a chord with me,’ she adds. ‘In this time of everything being in flux not only did I want to encourage myself into new reasons to be here, having lost people, but also to just ignore any of the hesitations that I would have put up in the past – be it financial, physical matter, time, what does it mean, what am I doing – all that stuff – and just do it.’

Initially, her art had combined the use of fabric sculptures and performance before she moved into inflatable artworks in 1998.

In the aftermath of her emotional shocks she began exploring other mediums and the use of different materials including bronze, clay, glass, poly-urethane and rubber.

Some of her new sculptural work using glass, urethane and bronze became part of a group exhibition at Sydney’s Stanley Street Gallery in February.

Photographer Murray Fredericks is another who has drawn on the experience of a series of personal shocks in his work. In the documentary Salt, filmed during trips he made to photograph Lake Eyre, he describes an ‘incredible series of events’ that he experienced in a matter of weeks at the age of 27. ‘I found out that my ex-girlfriend was having my baby; I found out that my Dad had cancer; I went blind in one eye spontaneously and then my Mum died. All that threw me into this turmoil that lasted about six months,’ he says.

During that time, Fredericks says he was barely able to function because of the intensity of the grief and all the overwhelming emotions.

As he began to return to some kind of normality after six months, he says: ‘I found that my whole sense of who I was; my whole sense of self; was gone. It was very different from what it was before anyway.’

It was an experience that would later be re-evoked by his trips over a period of six years to photograph Lake Eyre. ‘I find that when you’re that close to the void and the space is that overpowering you actually lose some kind of sense of self and I love pointing my camera into that emptiness, into that space and seeing what happens.’

Writer Suzanne McCourt, author of The Lost Child, is another who found grief helped her to move forward creatively, after her mother died in 2000. ‘Grief helps you deal with a lot of issues that otherwise you could keep buried under busyness and under work and under social happenings,’ she says. ‘It takes you into that deeper, private place where the writing comes from.’

‘I learnt an awful lot about letting go of control,’ she says about that time of grieving. ‘I guess I thought you could write from your head and it took me a long time to learn that I write from a deep inner space. It’s a very spiritual place I guess.’

Harvie says grief can also be connected to other forms of change, not just the death of a friend or family member. ‘It could be the death of a way of being, a partnership change, a return to self, having a child, not having a child, all those realisations and changes that happen.’

Those periods of change can actually bring with them an opportunity to connect more fully to yourself, she says.

‘When you’re in a state of drama and trauma you have a choice at that moment and you can choose to actually take yourself away in your mind from it or you can address it. In both of those cases it requires you just to be with you.’

She acknowledges it can seem easier to look outside yourself for answers.

‘When those things are taken away there is a sense of nothingness which is kind of like an empty potential but also a really scary blank space.’

But as she discovered: ‘In that state of crisis no-one can get to be with you quicker than yourself and what you realise is in the panic of thinking I need to call someone, get someone, someone has the answer to this or maybe somebody knows better what I should do, you find that the resource that needs to get there the quickest, the one that’s in the room, is yourself.’

It’s about listening to yourself both in your art and your life. ‘It might not just be your artwork,’ she says. ‘I would say to myself at a point of crisis and grief: why don’t we lie down for half-an-hour and then we’ll go up the road and have a nice big piece of chocolate cake. But I’m there. I’m not calling someone else who isn’t there.’

The result is you find yourself. ‘While you lose everything you gain yourself and once you find that you’re never alone,’ she says.

She advises people to feed the perception that there are still things to explore. ‘The main thing is that you are with you and you are allowing yourself to explore and tempting yourself that there will be more to come.’

In her case, those explorations led to a new direction in her art as well as a new relationship and motherhood.

_Encounters-in-Reflection_Gallery3BPhoto-by-Anpis-Wang-e1745414770771.jpg?w=280)