The past decade has seen increased recognition of the role women artists have played in art history, but often this is identified through gaps in the dominant narrative – narratives shaped by white men who have become gatekeepers and taste makers.

In her talk at the ‘Faith, Emotion & The Body in the Baroque’ Symposium held at Hamilton Gallery (in regional Australia), in conjunction with the exhibition, Emerging From Darkness: Faith, Emotion and The Body in the Baroque, Dr Esther Theiler says that men in the 16th and 17th centuries have long ‘neglected the ambition, fortitude and aptitude that was displayed by some women of the period in all areas of the arts and sciences’.

Theiler continues: ‘An honourable life for a woman back then revolved around the home. She’d engage in activities like drawing and painting, needlework and reading, but this was within an amateur context.

’Another option for a woman was life in a convent, where these are activities she might engage in but they’ll be serving a religious order.’

But Sofonisba Aguissola, Lavinia Fontana and Artemisia Gentileschi worked against these odds. Not only did they themselves become professional artists with wealthy patrons, but their own images have proliferated throughout their era and beyond. Theiler explains: ‘Each of these women needed to craft an identity. On one hand, the female artist was regarded as a novelty, a marvel… But on the other hand, some contemporaries regarded women artists less as anomalies and more as emblems of a civilisation at the peak of its glory.’

So who are these artists, and how did they succeed?

Sofonisba Aguissola (1532-1625)

Active between: c. 1550-1620

Patrons: Philip II of Spain, Duke of Alba,

Notable works: Self-portrait (1554), Portrait of the Artist’s Sisters Playing Chess (1555), Portrait of Marquess Massimiliano Stampa (1557)

On view at Hamilton Gallery: Portrait of a Prelate (c.1556)

Sofonisba Aguissola is widely recognised as one of the first known women artists, celebrated during her era and beyond for her talent in portraiture. Unlike many women artists who were able to gain training in the arts from fathers who were painters, Aguissola’s father was a nobleman who sent his daughters to receive education from local painters. Her talent quickly became apparent, gaining guidance from other practising artists including Michelangelo.

Aguissola’s Self-portrait (1554) is considered the first self portrait of any artist, male or female, to be holding a book. The painting and other similar works were sent by Aguissola’s father to notable people around Europe, ‘a highly strategic gift calibrated to spread Sofonisba’s fame and gain commissions’, explains Theiler. In another self-portrait dated 1556, Aguissola depicted herself painting a religious painting, rather than portraiture, showcasing a different side of her talent and capability as an artist.

Portrait of the Artist’s Sisters Playing Chess (1555), also known as The Game of Chess, is celebrated as an innovative painting, at a time when subjects weren’t allowed much facial expression. It’s a precursor to a naturalistic style that would follow in the coming century.

This step may have also been taken out of necessity to differentiate herself and bypass the restrictions placed on a painter of her sex and class, who would not be allowed to study anatomy, thus restraining her capacity to paint full-body and other religious images. A similar thread can be seen in Portrait of a Prelate (c. 1556) included in the Hamilton Gallery exhibition, where intricate details of the face contrast with the relative flatness of the body, predominantly covered by a black vesture.

Efforts towards Aguissola’s promotion were widely successful, and in 1559, Aguissola was invited to the court of Philip II in Madrid and became lady-in-waiting to tutor Elizabeth of Valois in painting.

While Aguissola’s eyesight deteriorated later in life, she enjoyed great success and recognition among peers and patrons. She herself is known to have influenced other female artists including Lavinia Fontana and Artemisia Gentileschi, while also becoming a patron of the arts.

Lavinia Fontana (1552-1614)

Active between: mid-1570-1614

Patrons: Duchess of Sora Constanza Sforza Boncompagni, Pope Gregory XIII, Pope Clement VII, Pope Paul V

Notable works: Portrait of Antoinetta Gonsalvus (c.1595), Assumption of the Virgin with Saints Peter Chrysologus and Cassian (1584)

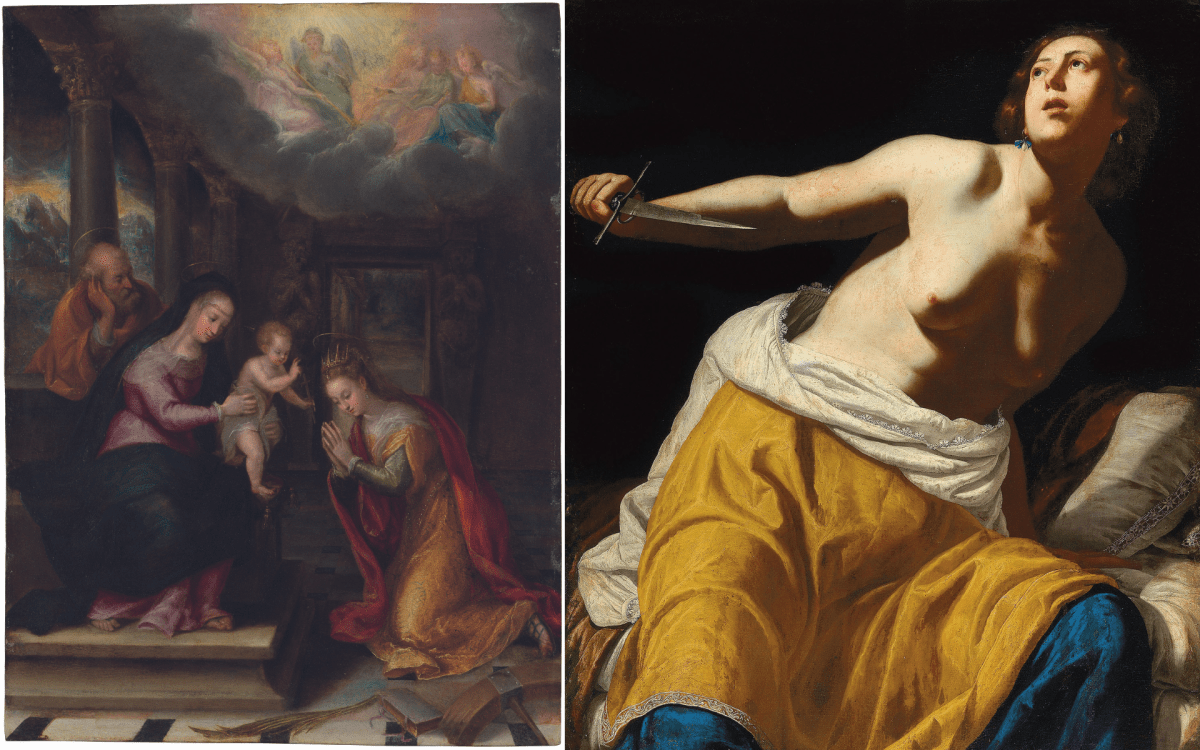

On view at Hamilton Gallery: Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (1574-7)

While many women whose fathers were painters sustained artistic practices, Lavinia Fontana is widely recognised as the most successful female professional artist of her era. She earned a living off her art that not only supported herself but also her family. Her father, Prospero Fontana, was a prominent Bolognese painter and teacher at the School of Bologna. Prospero saw Lavinia’s artistic potential and had the foresight to train her in the ideology of the Counter-Reformation, rather than the style of Mannerism that soon became outdated.

Lavinia Fontana didn’t marry until the age of 25, perhaps due to focusing on her artistic talent, and when she did, she was the breadwinner of the family. Her husband, Gian Paolo Zappi, was a fellow – though less successful – painter, who became her agent after marrying, and took care of their 11 children. This also meant that Fontana was able to continue painting through her pregnancies, which was an even more unlikely anomaly at the time.

For 20 years, Fontana was widely commissioned as a portraitist among Bolognese noblewomen, and after moving to Rome in 1604 at the invitation of Pope Clement VIII, she was appointed as Portraitist in Ordinary at the Vatican. The guild rules were changed by the Pope in order for Fontana to join as a woman.

However, there were still many restrictions and rules women had to follow at the time, including being barred from access to live male models, the requirement to be accompanied by men on outings, and the inability to sign contracts or manage their own finances. This is also the reason why many women artists, including Lavinia, were predominantly portrait painters, though she is also regarded (with some controversy) to be the first female artist to paint female nudes.

Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine (1574-1577), currently on display at Hamilton Gallery, was drawn around two years before Lavinia Fontana’s marriage and signed in her maiden name. In fact, Lavinia was heavily involved in her marriage arrangement, and presented two self-portraits to Zappi and his family prior to their meeting. This is also one of the earliest known paintings by Fontana.

Something else that has helped Fontana gain widespread recognition, both in her era and today, is the fact that she signed most of her pictures, which was very rare at the time, even for male artists.

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-c.1654)

Active between: c.1609 up until her death

Patrons: House of Medici, Cassiano dal Pozzo

Notable works: Salome with the Head of Saint John the Baptist (c.1610-15), Self-Portrait at a Lute Player (1615-17)

On view at Hamilton Gallery: Lucretia (c.1630-35)

Content warning: The third paragraph in this section makes references to rape and torture.

Similar to Lavinia Fontana, Artemisia Gentileschi was taught by her father, Orazio Gentileschi, who was also a well-known artist during his time and worked at the courts of Marie de’ Medici and Charles I.

Artemisia Gentileschi was also known for her self-portraits – which often show a strong confident woman – and was even popular among her patrons for embedding her own face into different female figures in paintings. Once her career matured, she was also able to hire female models, as was likely the case in Lucretia (c.1630-35), which depicts a partial female nude.

In her early years, Gentileschi worked alongside her father and brothers in his workshop, but was raped by one of her father’s colleagues in 1611, followed by a trial where she was tortured to verify her testimony.

Gentileschi was arranged into marriage with Pierantonio Stiattesi, a modest artist from Florence and moved to the city with him shortly after. Theiler says this move became a major turning point for Gentileschi’s career. ‘Here she reinvented herself, clothed in expensive silks and furnished her house extravagantly. It was all part of the strategy for making herself into a woman who could invite potential patrons into her home and be admitted into the most importance palaces – her goal was reaching patronage.’

In Florence, Gentilsechi became the first woman accepted into the Accademia dele Arti del Disegno and had good relationships with many patrons, including the House of Medici.

Up till her death, Gentilsechi was still receiving commissions, often featuring representations of women.

Read: Australian-UK collaborations driving artistic exchange and innovation

Apart from the three women painters mentioned, others have also left significant marks in art history as their stories are slowly being uncovered. Such include Flemish Renaissance painter, Catharina van Hemessen, who is believed to have created the first self-portrait of an artist (of any gender), while female artists were also well-respected throughout different periods in other regions, including Egypt and Asia.

But in order to fully recognise their achievement, we have to overcome our own bias and those embedded in fields across the arts.

Emerging From Darkness co-curator and Curator of International Art, NGV, Laurie Benson tells ArtsHub: ‘This is something that’s been turning on its head in the last five or 10 years, but art history is mainly run by men, and literally up until about 1970, women were pretty much written out of art history.

‘One of those reasons – and this is quite horrible – but curators, authors and writers in the past, if they saw a good painting, they’d say, “That couldn’t possibly be by a woman”. So there are probably thousands of paintings in galleries around the world that are actually by women artists, but they’ve been misattributed to men,’ adds Benson.

The hope is that the tides are turning, and one of the necessary steps is to become more educated on the achievements and ambitions of artists whose stories have too long sat on the margins.

Remember their names.

This writer travelled to the exhibition as a guest of Hamilton Gallery.