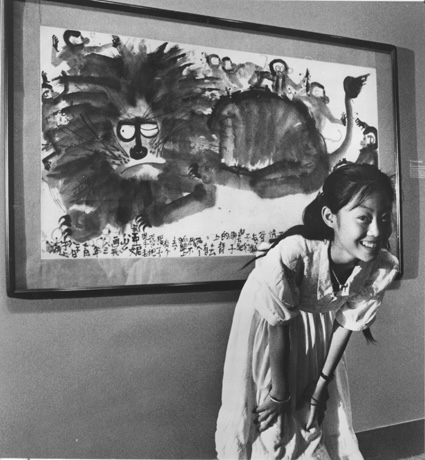

In the early 1980s, Chinese painter Wang Yani stunned the art world with her fresh take on xieyi-styled paintings of baboons, monkeys, cats and other animals.

As impressive as her paintings were, it was her very young age that was the primary source of the surprise and what dominated the reports about her. Wang started practising as an artist at two years old and was already exhibiting at the age of four. Garnering official recognition from across the country, her childhood work was featured on official Chinese postal stamps. By her early teens, Wang had found acceptance across the international art world with solo exhibitions in England, Japan, Germany and the US.

Yet, raw talent can only get one so far. A major factor of what allowed Wang to flourish as she did was the environment in which she was raised and especially the platform that her father provided, which enabled her to gain recognition in the modern art world at such a young age. Behind the scenes, her father, Wang Shiqiang, provided the support she needed to prosper artistically and to express herself freely, while also navigating the logistical and management challenges of the contemporary art world.

On the surface, Wang may seem to have just been a “child star”, as a sort of visual arts equivalent of Shirley Temple or Britney Spears. Yet, upon examining Wang’s environment, we see a stark difference. Some child stars are thrust into the spotlight by their parents seeking to capitalise on their youth. But Wang’s child-star quality was a byproduct of the personal and creative relationship she held with her father. Reaching audiences was a contingent surprise rather than a commercial goal.

Wang originally got into painting through a desire to help her father, an art teacher and professional painter himself. Her father gladly let her and it was through the relationship that evolved between them, that Wang soon began painting independently. Her father had to make personal sacrifices for her to flourish: he suspended his own practice so that his style would not limit Wang’s artistic development or the evolution of her own style. He only picked up the paintbrush again when Wang had fully grown up.

He also did not want her to become his direct “successor” and instead sought for her to emerge as an artist in her own right, which she did in adulthood. Wang eventually moved to Germany to become a reclusive artist, far from the public gaze with which she had grown up.

Wang’s story raises the question of how can children and their parents form a bond, where creativity is encouraged and enhanced, yet the family structure is sustained? Can parents raise their children to flourish creatively while fulfilling more conventional parental roles?

The family as a creative unit

The story of the Korean-Japanese “family” band, Tennger, provides a distinctive and intriguing response to this question. In their case, the family bonds have been integrated with, and are inseparable from, the art, as the family structure is used to inform the artistic one.

A musical couple, itta and Marqido used to regularly feature on the art festival circuit across Asia, Europe and US. Their experimental electronic music duo, 10, received international plaudits and they were widely hailed as among the most exciting indie electronic artists coming out of Asia in the 2000s. Yet, upon the birth of their son RAAI in 2012, they renamed themselves Tengger after the Mongolian term for “unlimited expanse of sky”, to mark the expansion of their family and in tribute to their status as a “nomadic travelling band”.

At just five months, RAAI was already travelling with his parents, observing them playing music and engaging with audience members – even before he could walk or talk. Through his parents, he was constantly surrounded by music and creativity. Fellow musicians welcomed his childish curiosity and let him play their instruments. Naturally, the more mundane realities of childrearing would sometimes take over, so that if RAAI started crying backstage, itta would have to rush over to feed him, leaving Marquido to play alone on stage to an understanding audience. It was never considered a nuisance, musically or otherwise, and was just a unique “signature” of the show, as well as foreshadowing the interaction and influence RAAI would later contribute to Tengger’s shows.

itta recounts: ‘One day, RAAI just started dancing on stage [since] he loves communicating with audiences and watching their eyes while he is on stage.’ Since then, RAAI has been officially as much a member of Tennger as his parents, and the three have since been playing together on stages around the world.

At their recent show in Naarm/Melbourne (Australia), this writer directly witnessed the creative fruits of this unique family ensemble. The family and creative relationship truly blossomed when all three members engaged with each other as much as they did with the audience, as some of RAAI’s own compositions were played. The show peaked with an ambient drone piece, when RAAI and itta walked into the crowd, gently shaking bells above their heads. itta’s had a slightly deeper pitch than her son’s, the contrasting tone evoking the feeling of a mother and her child calling out to each other through ambient music, in a way perhaps only a mother and child could do.

RAAI wasn’t a superficial or token stage presence, nor an artistic burden restricting or defining his parents’ expression, but rather the source of a warmer youthful sound, between his mother’s clamorous accordion set-up and his father’s synthesisers. They truly warranted the tag of a “travelling family band”, as each member was as much an integral part of the sound as any other.

When asked if itta and Marquido would like RAAI to grow up and be a musician like them, they stress that RAAI is free to do as he wants – he doesn’t have to continue in the band if he doesn’t want to and he is free to follow whatever artistic pursuit appeals to him. Their observation signals that for a creative family to flourish together, the relationship has to be natural and not forced.

Read: Performing and creating for children

Tengger provides an inspirational insight into how a creative family can foster self-expression from the youngest of ages in an unforced manner. However, as with Wang, Tengger’s circumstances are highly unusual and may be difficult to square with the prosaic reality of the typical suburban family.

The curious story of Meanjin/Brisbane-based musicians and label-mates, Sam Poggioli and Charlie Hill, provides a more typical blueprint for those who may want to foster a creative family, without compromising a stable suburban life.

The influence of creative parents

Poggioli and Hill emerged from fairly typical familial environments, but with creatively driven musicians and artists as parents. They met as children through their parents, as Hill’s father and Poggioli’s mother were both members of the Queensland Symphony Orchestra, and Hill’s mother taught art at schools, with Poggioli among her students.

Both grew up in relatively liberal households that encouraged but did not compel creativity. Poggioli’s mother and Hill’s father both pushed their sons to take part in music lessons, sometimes a bit forcefully but never overly so. Hence, when Hill wanted to stop learning piano to pick up the drums, his mother agreed. And they listened to different genres of music from their parents’ practice, and didn’t want to pursue careers in the same field. Neither was pressured to do so.

Raised in similarly creative households, Hill and Poggioli quickly bonded and both found their families to be hubs for creative evolution. In time, the two developed a creative hub of their own under Poggioli’s record label, Sampology. Their parents’ creative background, and generally supportive, but relatively hands-off approach, provided an enabling environment that led to them forging fresh directions for artistic expression, without following exactly in their parents’ footsteps.

Maintaining creative expression and raising children are demanding and complex challenges, seemingly at odds with each other. The restrictive view of an earlier generation was captured in Cyril Connolly‘s notorious aphorism, ‘There is no more sombre enemy of good art than the pram in the hall’. Yet, these two fundamental human instincts do not and should not be in fundamental conflict, and indeed can shape and inspire one another.

As seen from these diverse examples, raising a child should not restrict an artist’s own creativity, but instead can spur new directions for artistic expression, both for the parent and for the children, who will naturally find their own voice as they grow and define themselves beyond the penumbra of their parents’ influence.

This article is published under the Amplify Collective, an initiative supported by The Walkley Foundation and made possible through funding from the Meta Australian News Fund.