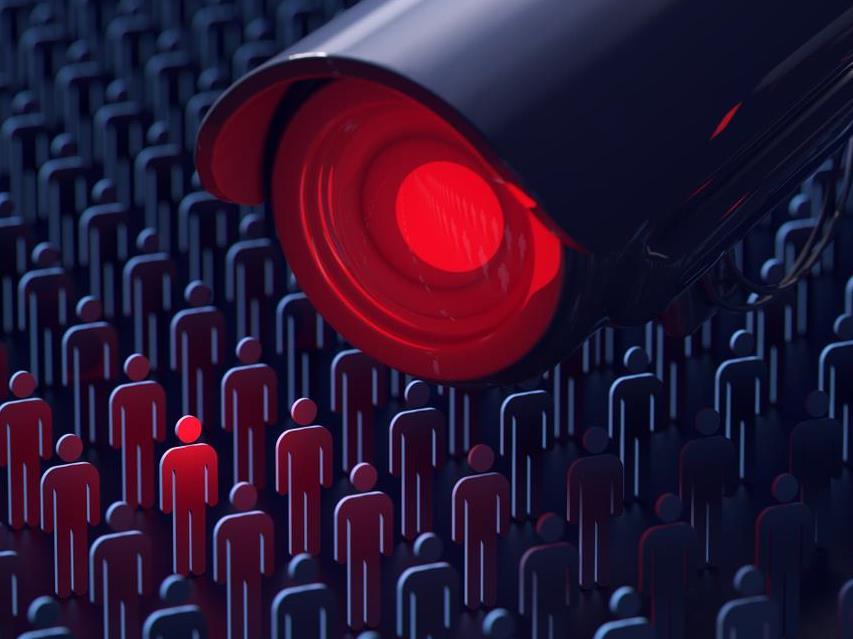

Many Chinese dissidents are surveilled by the Chinese government; image Shutterstock.

It was 2009 when the Chinese political cartoonist Badiucao brought himself to voluntary exile in Melbourne, 2013 when he became an Australian citizen. Despite the relative political safety that move gave him, he has for years masked himself whenever he has gone out in public. He goes under an assumed name and years ago broke off contact with his family for their safety.

He publishes his work – clever, loaded with significance, and visually appealing – on the internet. He communicates with his followers through Twitter and has had his images go viral around the world. They have been put up in public places, curated by political activists and copied as graffiti.

Last year, he discarded his disguise. On the eve of a radical show in Hong Kong, which had been secretly and strategically planned, he discovered that his family had received visits from the Chinese police. He learned that they planned to visit his show. They knew who he was. His security, and that of his family, was compromised.

He shut down the show the day before it opened, a dramatic moment in the fascinating documentary about him, China’s Artful Dissident, that premiered here in May – and in Hong Kong in June. Revealing his face was the denouement. He goes unmasked now, but still uses his single name and steers clear of his family just in case.

Badiucao was working in Berlin with Ai Weiwei, another self-exiled dissident whose studios in Shanghai and Beijing have been dismantled by the government just in the last year. ‘I had planned to stay with him for three to five years, helping him and learning from him. The experience was quite remarkable, very rewarding,’ he said. ‘But after what happened in Hong Kong, and to my family, I decided it was safer to come home to Australia, where I am a citizen.’

Writers under surveillance

Badiucao is one of the many dissident Chinese artists that are constantly surveilled by the Chinese Government, many of them ending up in jail. Liu Xiaobo – writer, philosopher activist – is perhaps the most famous, having been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in absentia in 2010. A supporter of the Tiananmen protests in 1989, he was detained after signing the Charter 08 political manifesto in 2008 and formally charged with ‘inciting subversion’ the following year. He died of cancer in 2017, having been released from jail to spend his last days at home. Badiucao has drawn an evanescent and evocative suite of drawings of him and his wife in the final moments of his life.

This month, the Australian writer Yang Hengjun, an advocate for democracy in China, was formally charged by China, seven months after being detained on a visit to Beijing. A former Chinese diplomat who moved here in 1999, and now a writer of espionage thrillers, he was charged with spying. It’s a charge Australian Foreign Minister Marise Payne has robustly dismissed, adding that the Australian government is ‘very concerned and disappointed’ by China’s action and demanding decent conditions in jail and legal representation for him.

Badiucao was right to return home when China unmasked him. Payne is doing what she can for Yang, and is presumably negotiating behind the scenes too, in a difficult moment of heightened tension between Australia and China. The Government’s obligations to protect artists is the same as for any other citizen, though their protocols can be strained by the politically charged free-speech stance that artists can take.

China is increasing its surveillance and intimidation of Chinese citizens and descendants overseas. The increased surveillance of, and through, Chinese students studying overseas, concerns about the security threat posed by Huawei, the tendency of Chinese-language newspapers, even here in Australia, to toe the Chinese Government line: this is the context in which artists in the Chinese diaspora are struggling to work.

Badiucao, CCTV. Image courtesy of the artist.

Hardening of China’s power

China is swapping soft power for hard power and stepping up interference in foreign countries as it grows. When I wrote a piece for The Australian in 2011, about China using its art as international soft power, Hugh White, professor of strategic studies at the Australian National University, had just published a Quarterly Essay on China-Australia relations. ‘China has a formidable task ahead of it to reassure the world, and particularly its neighbours, that even when it is a very strong country, it will still be a country we can trust,’ he said. ‘The Chinese, in a quite focused and deliberate fashion, are trying to offset distrust.’

Much has changed in a scant eight years. White told ArtsHub, ‘I think it’s clear that as China’s power and ambitions have grown, as its domestic politics have hardened, and as resistance from others to its growing influence have crystallised, Beijing has become markedly less concerned to soothe other countries’ fears, and more content to build influence with sticks rather than carrots. And we can expect that trend to continue.’

Richard McGregor, China analyst at the Lowy Institute, points out that we are on China’s radar for several reasons, domestic and international. ‘There are more ethnic Chinese here, both students and immigrants,’ he said. ‘We’ve been a thorn in China’s side for the last three or four years.’ He mentioned Huawei, the foreign influence debate, our participation in patrolling the South China Sea, and Malcolm Turnbull’s warning to China. When Turnbull was Prime Minister, in 2016, he initiated a no-longer-secret ASIO investigation into China’s influence in Australia. And now we’re caught between a rock and a hard place in the middle of the China-US trade war, between our largest trading partner and our closest ally.

Badiucao is critical of Australia’s diplomatic response to China, especially over Hong Kong. He is also critical of the weakness – the scarcity and penetration into public discourse – of political art in Australia. It’s interesting to compare the ease with which he criticises the politics of his adopted country with the tension in his voice when he speaks of China.

Does the heightened geo-political tension have a silencing effect on the Chinese artistic diaspora? And is it increasing? ‘Definitely,’ Badiucao replied. ‘People like me will have more and more difficulties. We’ll have to have more courage in order to speak up in the future.

‘But we either speak up, or remain silent and waste our lives.’

———

Screenhub and Artshub covered the screening where Badiucao finally showed his face in May. It was an extraordinary moment.