Image: Snugglepot and Cuddlepie play cricket – a postcard by May Gibbs, created around 1916, and now out of copyright.

The look and feel of Paper Planes, which has now made $8.2m at the Australian box office in five weeks, reminds us just how few opportunities Australian children’s producers have to dive deeply into the lives and conversations of our own children. We are forced to spend a lot of public money to produce an internationalised version of ourselves, which is then fed back to our kids.

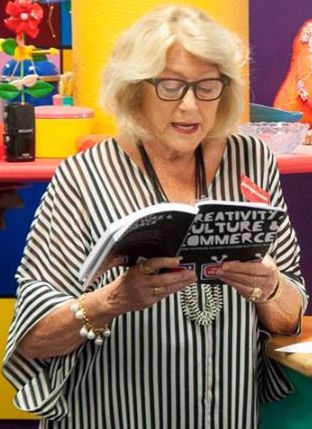

On Tuesday February 10, the Australian Children’s Television Foundation hosted the launch of Anna Potter’s widely researched book, ‘Creativity, Culture and Commerce – Producing Australian Children’s Television With Public Value’.

On Tuesday February 10, the Australian Children’s Television Foundation hosted the launch of Anna Potter’s widely researched book, ‘Creativity, Culture and Commerce – Producing Australian Children’s Television With Public Value’.

It was a genteel occasion, concealing the fact that a lot of advocates for our culture would like to run a stump-jump plough through the current media landscape to get some attention from our international overlords. Janet Holmes à Court, chair of the ACTF for 29 years, and a formidable fighter for the public good, officiated with grace and clarity.

‘The film and television industry is in a period of enormous change and perhaps audiences have more choice than ever, but not if the reality is that this choice all looks and sounds the same and comes from a few enormous global corporations,’ she said. ‘We need to ensure that we celebrate our independence, that we carve out a space and nurture our stories and ensure that children get to find them and own them.’

She laid out the issues in Potter’s book in one neat list:

- how broadcasters treat children’s content and what they pay for it.

- What it costs to produce drama compared to other types of television.

- The regulations that underpin children’s content on commercial stations and the role of the regulator, ACMA

- the important involvement of the ABC and the pay tv children’s channels,

- where the rest of the funding comes from, and the dependence on international finance,

- the internationalisation of children’s program content and of the production sector itself.

‘Anna outlines how this industry is changing in the digital era, and asks all of us, but especially policy makers, to consider how best we can secure public value for public investment in children’s television, and in turn for the children’s audience, in a new age of niche channels, fragmented audiences and ever increasing globalisation.’

The book is available at the ATOM Shop.

Like everything else in our sector, the infrastructure is fundamentally artificial, generated by governments acting on social principles embedded in culture and commerce. The introduction to Potter’s book provides a useful summary of the issues, and embeds them in this deeper politics.

Here it is:

——–

CREATIVITY, CULTURE AND COMMERCE: Producing Australian Children’s Television With Public Value.

By Anna Potter

——

Introduction:

This book is the story of the dissolution of long-standing settlements in Australian children’s television that occurred from 2001 to 2014 during Australian broadcasting’s transition from an analogue to a digital regime. It is an account of how changes in the creative, economic, technological and regulatory circumstances in which children’s television is produced and distributed gradually undermined the ability of much contemporary Australian children’s television to speak directly to Australian children. It explains why Australian children’s television, particularly live action drama, has a global reputation for excellence, while the circumstances of contemporary production have rendered children’s live action drama one of television’s most vulnerable genres.

A set of public value principles that underwrite and authorize the Australian policy settings designed to ensure supplies of children’s television is also identified here. These principles recognize that much of the worth of the Australian children’s television made with state support lies in its ability to situate Australian children within their own culture (in contrast to any monetary returns generated through its programme sales and merchandising activities). The complexities of creating identifiably Australian children’s television, with both state subsidy and significant international investment, for fiercely competitive local and global markets in digital regimes are described here as well.

As the following chapters make clear, the production of Australian children’s television is at a critical juncture. In the 1960s and 1970s, public concern about the lack of wellproduced, locally made television available to Australian children led to the establishment of important policy instruments including, in 1979, the Children’s Television Standards (CTS). The CTS are intended to ensure that age-specific drama, animation, reality, quiz and game shows, and entertainment and documentaries are offered to children by Australia’s commercial networks. The benefits for the child audience of having access to a variety of television programmes, including locally made live action drama, justify the levels of state subvention required for their production. When Australian children’s best interests are met through the provision of television that situates them within their own social and cultural context, this valuable form of cultural production meets its policy objectives.

As the following chapters make clear, the production of Australian children’s television is at a critical juncture. In the 1960s and 1970s, public concern about the lack of wellproduced, locally made television available to Australian children led to the establishment of important policy instruments including, in 1979, the Children’s Television Standards (CTS). The CTS are intended to ensure that age-specific drama, animation, reality, quiz and game shows, and entertainment and documentaries are offered to children by Australia’s commercial networks. The benefits for the child audience of having access to a variety of television programmes, including locally made live action drama, justify the levels of state subvention required for their production. When Australian children’s best interests are met through the provision of television that situates them within their own social and cultural context, this valuable form of cultural production meets its policy objectives.

Unfortunately, there is a growing disconnect between the achievement of long-standing policy objectives for Australian children’s television and the production of much of the children’s television that is made in contemporary Australia. Many of the causes of this disconnect lie in the fragmentation created by digital television regimes that caused a shifting of the sands under commercial television. From 2001 onwards, as Australia embarked on its digital transition, free-to-air channels proliferated, pan-global pay-TV networks matured and multi-platform delivery became the norm. Audiences, including the child audience, fragmented across multiple platforms. So did advertising revenue and programme budgets.

Fragmentation challenged long-standing business models for television and exerted downwards pressures on the licence fees networks were prepared to pay for programme rights. Reduced licence fees further increased the need for the international investment that Australian producers have always required to finance their children’s programmes. New policy instruments that came into effect during the digital transition created additional incentives for the independent screen production sector to internationalize, despite a significant screen policy emphasis on the achievement of the goals of national cultural representation. The combination of fragmentation and increased internationalization led to new production norms in Australian children’s television that reduced quality standards and cultural specificity in many programmes. The new production norms often undermined the ability of these programmes to speak directly to Australian children.

This book is not, however, a narrative of decay and demise. Many of the changes that accompanied the digital transition were of enormous benefit to children’s television, with the potential to substantially increase its production and cultural visibility. Abundant spectrum and multi-channelling created niche television markets and enabled Australia’s commercial networks to provide dedicated destinations for their children’s television offerings for the first time, on their newly established multi-channels. The public service broadcaster the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) was able to launch Australia’s first free-to-air dedicated children’s channel, which quickly became the most popular children’s channel in Australia. Fragmentation meant, too, that the child audience became highly sought after, by pan-global subscription networks and public service broadcasters alike.

During the digital transition Internet-based television services such as Netflix confirmed the international popularity of high-quality Australian children’s drama. These new mechanisms of distribution have the potential to remove broadcaster involvement from distribution arrangements that can see a children’s drama premiere in 51 countries on the same day. Australia remains a safe, sunny, stable environment in which to film, where a canvas can be created that the rest of the world wants to see. Australian screen producers are still passionate, resilient and highly accomplished storytellers, while Australian children’s television retains a global reputation for excellence first established in the 1980s. A range of state subsidies designed to encourage screen production in Australia continues to be offered. Clearly digital regimes create exciting new possibilities for the production and distribution of children’s television.

The Australian children’s programmes that secured distribution on the pan-global networks, or Internet-based services that developed during the digital transition, enjoyed international sales and increased cultural visibility. But while some culturally specific Australian drama continues to circulate in global markets, international distribution and co-production arrangements frequently entail a loss of cultural specificity and with it a capacity to speak directly to Australian children. As a result, many contemporary children’s programmes made in Australia neither look nor sound Australian. Frequently these programmes are not even based on Australian stories. Their ability to situate Australian children within their own culture is therefore diminished. The effects of internationalization on Australian children’s television were amplified during the digital transition, when a combination of market forces and new policy settings encouraged international investment in both Australian programmes and in the production companies creating them.

The market conditions that accompanied the digital transition not only increased the need for international investment in Australian children’s television, they also favoured the production of animation over live action drama. Animation is often cheaper to make, and much more easily distributed, largely because it tends to be a less culturally specific form of storytelling than live action drama (and in any case is much simpler to revoice).

Many governments are prepared to subsidize its production in order to establish or retain animation production industries. Animation is a perfectly legitimate and enormously popular genre, long considered as children’s drama by Australian policy-makers. It can be used to fill content quotas in exactly the same way as live action drama. But the skewing of the ratios between animation and live action drama from the mid-2000s exacerbated the loss of cultural specificity and contributed to the downturn in production values in much contemporary Australian children’s television.

Public activism in the 1970s persuaded the Australian government to introduce policy settings, screen organizations and funding mechanisms that would support the production of Australian children’s television by an Australian independent production sector. Generally these instruments of state support are financed by Australian taxpayers; thus the Australian public has always been a key stakeholder in the production of children’s television. In this environment, producers, networks, regulators and screen bodies ignore the public, notions of public value and their responsibilities to the Australian taxpayer, at their peril.

Public activism in the 1970s persuaded the Australian government to introduce policy settings, screen organizations and funding mechanisms that would support the production of Australian children’s television by an Australian independent production sector. Generally these instruments of state support are financed by Australian taxpayers; thus the Australian public has always been a key stakeholder in the production of children’s television. In this environment, producers, networks, regulators and screen bodies ignore the public, notions of public value and their responsibilities to the Australian taxpayer, at their peril.

State support for children’s television brings its own set of obligations to the Australian public, which campaigned for those vital measures and continues to fund them through taxation. But since 2001 producers, networks and regulators have been engaged in intramural conversations about the funding of children’s television that have largely failed to include the public. A sense of a reciprocal obligation to the Australian public in return for regular access to various taxpayer-funded supports for their children’s production slate can, at times, be difficult to detect. The supports that are available to those who produce children’s television in Australia are predicated, however, on the understanding that children are a special and distinctive audience. When the children’s television produced with state support fails to situate Australian children within their own culture, justifications for public subsidies of the genre are undermined.

When the Australian public is recognized as the key stakeholder in children’s television, the risk that various policy instruments including the CTS become seen as mere measures of industry protectionism is reduced. If the public and the importance of the achievement of long-standing policy objectives for Australian children are forgotten, however, the screen production industry is in danger of becoming hostage to its own sense of entitlement. When the special status of the Australian child audience is ignored, the industry behind it becomes just another industry. Creative industries may well be deserving of some form of state subsidy, but the state subsidies that underpin children’s television in Australia were never intended to be mere industry protectionist measures.

Ten years ago confident predictions were made that the Internet would lead to television’s demise, while the lack of regulation surrounding the new medium caused public concern to shift to the need to protect children from the dangers of the online environment. It became increasingly obvious during the digital transition, however, that the Internet rejuvenated television, including children’s television. Free-to-air television remains the most popular television in Australia, with ‘second screen’ activities often accompanying viewing, particularly children’s television viewing. While legitimate concerns about children’s use of the Internet remain, it is time for public focus to return to the continued provision of high quality, locally made television for Australian children. The public should be encouraged to engage in debate about how best to secure value for its investment in the genre, and in turn for the Australian child television audience.

In order to have that debate, the increasingly complex settlements in children’s television that emerged during the digital transition require scrutiny, so the changes in production, distribution and consumption can be understood. It is entirely possible that after a period of reconsideration and reimagining of Australian children’s television a new and dynamic set of production and distribution norms could develop. Australia’s international reputation for excellence in children’s programming would be maintained and indeed, enhanced. Such developments would require a significant rethinking and refashioning of existing policy settings and, particularly, the means of securing supplies of locally made, high-quality, age-specific television for the child audience. Australia’s commercial networks continue to sit at the heart of Australian television production. They remain central to the achievement of these policy objectives, despite their long-standing reluctance to invest in television deliberately made for Australian children.

From 2001 to 2014 the transition to a digital regime in Australia led to the emergence of new settlements in Australian children’s television. It is essential that all those committed to the creation of high-quality, culturally specific television for the child audience acknowledge the transformations that occurred during this period. While contemporary Australian children’s television experienced renewal, as old patterns of production and distribution dissolved, this renewal was accompanied by a gradual reduction in television’s ability to situate Australian children within their culture and hence its public value. Australian children’s television can still ride the digital wave that has reinvigorated contemporary television but the rethinking of the institutional, economic and regulatory arrangements that underpin its creation and distribution is a matter of urgency now.

—-

© Dr Anna Potter, +61 7 5430 2846, apotter@usc.edu.au

Images courtesy of ACTF.