Many individuals and much of the creative industry has experienced a collective, enforced pause due to the pandemic.

For some, the financial strain or resulting piled-on responsibilities might mean you’re busier than ever. For others, the pause or slower pace might have brought a sense of relief. For others, it brings a feeling of discomfort or unease to be doing less, even when it can be afforded.

If you relate to the latter category, you might know on one level that breaks and rest are invaluable, but yet cannot shake the sense of uneasiness.

Why do others find it easier to embrace a break, to pause or to rest?

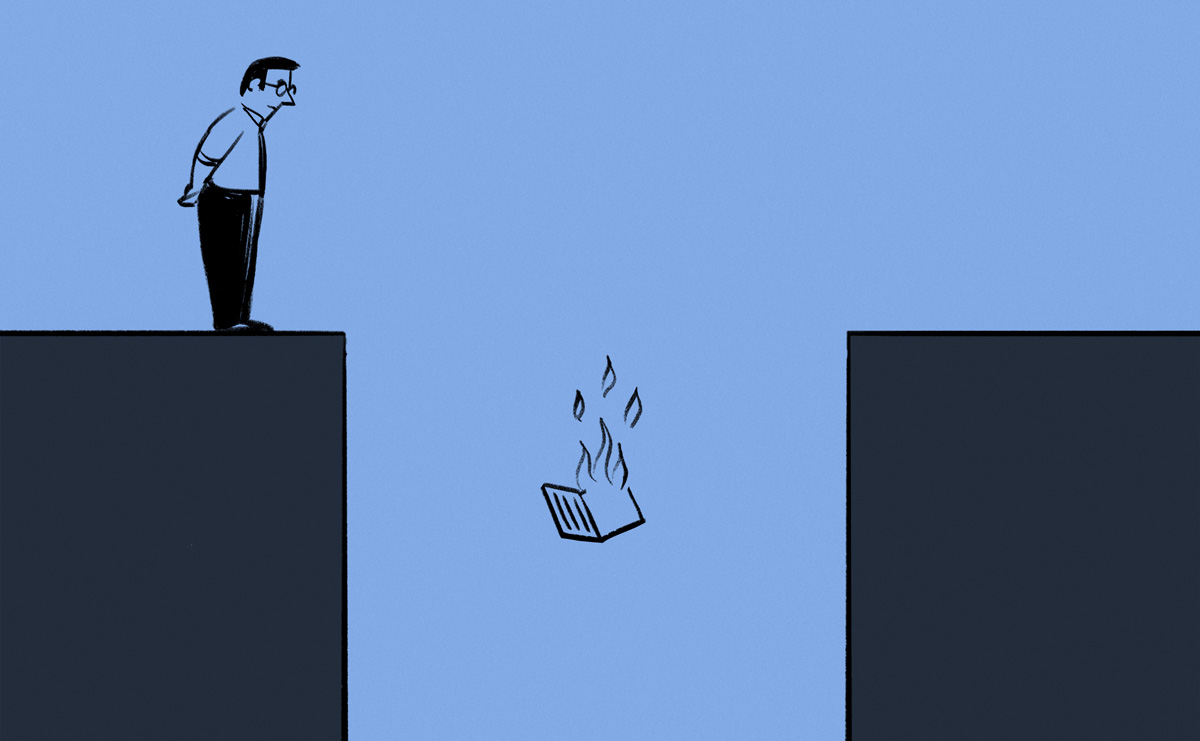

It could be that a break has always had two sides. We can feel the loss and grief of say a broken heart, but we also seek the break of a holiday. A pause can be both what disorientates us, and what sustains us.

It could also be related to our relationship to inertia, or not working, and work. In Not Working: Why We Have to Stop, psychoanalyst and writer Josh Cohen outlines how our relationship towards inactivity can create comfort or discomfort.

‘There are some of us who seem to be more in touch with the inactive dimension of ourselves and recognise that we need to sometimes expand and be active in the world, but also to contract, stop and just be,’ said Cohen.

While this expanding and contracting or ebb and flow might be innate, often people are quick to fill the gaps that appear in our lives, be it space or time.

This can, at times, be a missed opportunity to ask deeper questions about our relationship to work, explains Cohen. ‘An enforced pause for those who are not experiencing immediate anxiety about their survival is giving us the opportunity to ask questions such as, “Why do I think of external activity as being the only legitimate form of being?” “Why would it not be possible to allow oneself to sit out of it, to be a bit aimless and to drift?”’

Learning from the different not-working archetypes

It can be difficult to aimlessly drift when we feel a sense of anxiety about the thing we should be doing, or experiencing the very real anxiety of job loss or insecurity.

Yet as Cohen describes, entering into a persecutory mode where we accuse ourselves of not doing enough isn’t conducive to creative work.

‘The more you accuse yourself, the more you fail to do what it is you’re supposed to be doing and your day turns around this self-accusation that entrenches itself more and more, and never actually allows you to get on to what you want to do.’

For Cohen, the antidote can be to embrace the drift in small pockets of our days. Taking an aimless walk or having an aimless conversation are examples – both that make room for surprises in our daily lives, which in turn can fuel our creativity.

‘If we always know what we’re doing then we lose the capacity to experience something unexpected,’ he says.

In fact, boredom is an important part of our working lives. ‘It opens the space for us to hear something or see something, perceive something in ourselves and out there or both that surprises us.’

This is where learning about the four inertial archetypes outlined in Not Working – the burnout, the slob, the daydreamer and the slacker – can teach us about our own relationship to drifting, boredom and not working.

‘Each of these types, by volition or necessity, has stopped working, or at least working blindly,’ explains Cohen.

The four types are divided into two groups of two: the burnout and the slob fall under gravity, and the daydreamer and the slacker fall under anti-gravity.

By learning about the types and seeing parts of ourselves in them, we can hopefully form gentler ways of not-working, perhaps even when it’s enforced, turning the discomfort we might be feeling into an opportunity for curiosity.

‘Think of them less in terms of models for living, and more in terms of what they can tell us about our own inactive, drafting sides or weary overactivity. Instead of asking ourselves whether or not we want to become a slob, we say what is it the slob can tell me about my life?’ says Cohen.

Gravity types

The Burnout

The burnout often wonders if they are doing it right, and experiences guilt and shame when they are not doing, and tend to sabotage both work and rest.

‘What has happened with the burnout is that they’ve been forced to submit to the law of gravity. They’ve tried to defy it, they’ve tried to turn themselves into perpetual motion machines whom gravity will never touch and then suddenly they find themselves collapsing and succumbing the force of gravity.’

The Slob

The slob can often be seen as lazy and complacent, but there is creative potential in destructiveness. They have a passion for inactivity, and just as they strive for their creative ambitions, they also refuse them and allow themselves to just be.

‘The slob embraces the force of gravity. This often comes with a background sense of entitlement and yet what we can learn from the slob is how their sense of internal equilibrium and peace comes first,’ says Cohen.

Anti-gravity types

THE DAYDREAMER

The daydreamer floats above daily reality, often acting or stepping into a creative pursuit. The daydreamer might seem idle to others, but often incredibly disciplined and prolific.

‘The daydreamer teaches us that a lot of activity or even travel in the world is something we can do in our own heads. Our curiosity can open up possibilities that don’t really require us to leave the house,’ says Cohen.

The Slacker

The slacker often oscillates between wanting their time to belong to them, and then wanting to be accountable to others.

‘The slacker is not necessarily somebody who is lazy, but somebody who tries to find a way of living that is geared to their own internal rhythms rather than rhythms that are imposed by outside,’ explains Cohen.

The tension between doing too much and doing nothing

During our working lives there can be tension between doing it all, and doing nothing at all, between working and not working. In this profound moment in time, we face the tension of a global pandemic that might be bringing a pause and the global attention on systemic racism and oppression that requires action, protest and mobilisation.

For Cohen, there may not need to be a tension between work and not work, pausing and action, work and life, doing and not doing.

‘I think the book is trying to argue for a much more intimate relationship between working and not working. Instead of thinking in terms of a binary, you start to see not working as part of the texture of work, which would hopefully make it much easier to switch off and allow yourself to do nothing.’

Read: How to procrastinate properly

Cohen’s advice? ‘Try to make space every day for ways of being with yourself that cannot be added to the to do list.’

Creativity in particular can benefit from the moments we give ourselves nothing to do – it’s often in the drifting or not working where we can have our best ideas.

Similarly, there isn’t such a clear binary between starting and stopping. There’s a lot of emphasis placed on getting started when it comes to creative projects – just do it, make it happen, don’t wait for inspiration, begin now.

Yet in the creative process, getting started has a lot to do with how well we stop.

As Ernest Hemingway said, ‘I learned never to empty the well of my writing, but always to stop when there was still something there in the deep part of the well, and let it refill at night from the springs that fed it. I always worked until I had something done, and I always stopped when I knew what was going to happen next. That way I could be sure of going on the next day.’

Taking the break often helps us see what we need to do – it can crystallise what we have been afraid of as it gives us space to inspect. And it also prepares us for action because more often than not, the antidote to being afraid of the work is doing the work.

As Cohen adds, ‘Don’t imagine there has to be a particular place to start with a creative project, start wherever your mind takes you and allow the process to lead you instead of trying to grab hold of the process itself.’

Allowing for the pause is what teaches us to take things step by step, to start small, to find calm, even joy, and make space for the inevitable ebb and flow of the creative process, and our lives.