Image: tnooz.com

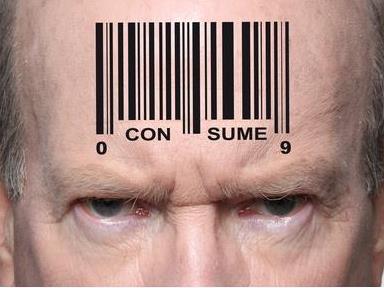

Museums and galleries today (used interchangeably here) are complex ecosystems, no longer the hallowed halls of silent reverence extended only by weighty tomes. What once started out as a specialist bookshop with a few collection postcards and the odd poster, has become big business for galleries, from global brands like The Met (Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York) – which even has outlet stores in Australia – to pop-up vitrine stores in most regional galleries providing a vital income stream.

Simply, to exit through the gift shop – to adopt the title of street artist Banksy’s film from 2010 – has become standard modus operandi.

The gallery shop and the gallery café or restaurant have changed the dynamic of galleries, both from a social and economic standpoint. British writer Paul Arendt reminds us that it is almost 25 years since the Victoria & Albert Museum’s Saatchi-devised marketing campaign was ‘lambasted for branding itself as “an ace caff with quite a nice museum attached.”’

And as the stand-in original artwork – that is your postcard and poster – has been adopted by places like IKEA and digital printing technologies, the gallery shop (like the café with its celebrity chefs) has turned to more innovative and temporary targeted merchandising to maintain that dollar. We only have to look at the spin-off merchandising of blockbusters.

However, the concept of the art souvenir is not entirely new. What has altered is the volume and ubiquitousness of it – and that spells money.

Writer Toby Fehily contextualised the history of art souvenirs dating them back to Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York in the 1870s: ‘From its earliest days the museum was selling $25 sets of Old Masters engravings. Thanks to one Bradford Kelleher, an aspiring cartoon animator who joined the Met as a sales manager in 1949, the museum’s art and book shop grew from what was once described as “little more than a rack of postcards’ to a business that pulls in approximately $70 million per year – more than what the museum makes from admissions and memberships. Today The Met has satellite souvenir stores across the world, including three in Australia alone.’

Merchandising has become less about collection and more about connection – call it trends if you want. This is not entirely unfamiliar to Australians. Ken Done was the master of art-inspired merchandising in the 1980s. He explained at a SAMAG talk last year, that for his first solo exhibition at Art Directors Gallery in Sydney, Done painted a handful of Sydney harbour t-shirts for media. The t-shirt now is a perennial seller in the gallery shop, collection or exhibition themed.

Only last week Nick Mitzevich at the opening of Trent Parke’s exhibition at the Art Gallery of South Australia, had a museum attendant proudly modelling a dead rat t-shirt to his shop spiel. Mitzevich has openly advocated the merchandise model for galleries.

Joining Parke’s t-shirt in triggering this article were two emails that arrived in the weekly deluge: Queensland Art Gallery I Gallery of Modern Art’s (QAGOMA) announcement of David Lynch merchandise to coincide with its exhibition Between two worlds (14 March – 7 June) – highlighting a unique Lynch blend of coffee – and Museums and Galleries of NSW (MGNSW) encouraging opportunities for regional galleries.

They followed a talk presented a few weeks earlier by Richard Harling at the 2015 National Public Galleries Summit in Bendigo. Harling was Manager of Retail and Publishing at the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW) for over ten years and in 2013 started his own business The Cultural Commerce Consultant, working with major cultural institutions.

David Lynch merchandise developed by QAGOMAfor their current blockbuster exhibition.

The consistent message across these voices was that branded merchandising is the new golden road to success with the rise of the temporary, exhibition-related pop-up shop. Get it right and you tick an audience box and a dollar box.

Retailing today is key in strengthening the viability of public art galleries, and as Harling said: ‘The holy grail is to enhance visitor experience.’

‘There is a saying in retail, “don’t sell the product, sell the experience”. When people come to the gallery they either view the shop first or last – these are the strongest impressions,’ continued Harling. ‘We all know about retail; we know how to be a customer. It is a really natural place to make connections with a gallery.’

Harling reminded that that plastic dinosaur or fridge magnet is not only a tangible reminder of a positive experience, but it advocates you as a museum to others. Build on that. When you think about your products don’t focus on things, says Harling, rather think of a range. You want to tell a story; and that story will be shared.

Talking to the sector, the MGNSWs website advises: ‘A variety of small and economical souvenirs can (be) sourced online, simply provide artwork or design and allow up to 6 weeks before goods are received…It’s possible to generate significant funds through selling visitors’ experiences to them again in the form of a tea towel, fridge magnet or local crafts.’

NGVs silk scarf by Australian fashion designer Linda Jackson features Leonard French’s stained glass ceiling from the gallery’s Great Hall, bringing together two icons and creating unique merchandise that captures an experience specific to that cultural institution.

Great Hall ceiling silk scarf by Linda Jackson sold at NGV store for $195.

But MGNSW warns: ‘Made in Indonesia boomerangs and tea towels, key rings and umbrellas designed and made in China bearing misappropriated Aboriginal motifs have no place in cultural institutions.’ Talking to local designers, craftspeople and Aboriginal communities, the likelihood is that they would welcome the opportunity for an outlet, and are a better fix in terms of volume. One of the problems smaller galleries face is buying power. Suppliers often mandate a minimum order, or face high costs.

A good example is Sydney Living Museums (SLM), which operates four substantial shops: the Museum of Sydney, Hyde Park Barracks, Susannah Place and Vaucluse House and supplies themed merchandise for sale at several of its other properties.

Galleries and museums need to be alert to the exhibition and merchandising cycle. While the biggest sellers might reflect a temporary or blockbuster exhibition, as with food merchandise has a shelf life. There is a finite window of sale, and a bit like Lynch’s coffee beans turning stale, themed merchandise will have a “has-been” feeling as soon as the exhibition closes.

QAGOMA is widely recognised as one of Australia’s most successful gallery shops, headed up by Peter Beiers, who joins Harling in reputation in this niche industry. The National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) has also enjoyed success, its most recent pop-ups responding to the successful David Shrigley: Life and Life Drawing and Romance was born for kids exhibitions, while the National Gallery of Australia did well with parasols and tutus for their Toulouse-Lautrec retrospective.

Romance was born baby onesie by Kate Rohde for $100 at the NGV store.

Reading the cultural consumer zeitgeist is key. How do you do that?

Stephen Quinn, of the National Museum Shop, embraces the mantra “educate, entertain and entice”. He spoke at the 2014 Regional & Public Galleries Conference demonstrating the economics of success in rebranding the Museum’s shop and planned merchandising. You can watch his presentation courtesy MGNSW.

Harling echoed Quinn’s views. ‘There is an expectation now that you must be sustainable. The money you make in the commercial operations is yours. It is not tied in any way (as government funding is).’

He offered: ‘Use your training budget. Rather than do and OH&S course, do a retail management course.’

‘And if you can’t do 1000 umbrellas, then do a tote bag instead. You have to know what you can sell,’ he said.

‘Benchmark – try to talk to each other about what works,’ advised Harling, adding to Quinn’s idea that to pool resources and buying power.

Shop til you pop at AGNSW store.

American writer Jed Perl, in comparison, is among a backlash to the trend, criticising global brand museums for their rush to be the latest “tourist trap”. ‘MoMA has been looking more and more like a f__king department store since the greatly expanded museum reopened in 2004,’ he writes in a scathing article in 2014, aligning the whole department store approach with the culture of new museum architecture, sleek and deliverable.

Unfortunately for Perl, the gallery shop is here to stay. And with MGNSW reporting that one small gallery under their umbrella had an increase of 28% in gallery revenue accounted for by merchandise sales, this impact is even greater at a micro scale as other funding sources continue to dry up.

And now with the capacity to extend the gallery shop – and these exhibitions – to a broader market online, it is only going to continue to grow as a robust revenue stream of our museums of the future.