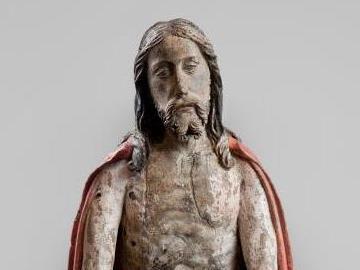

Marc Antoine du Ry, The Derision of Christ, National Gallery of Victoria

The philosopher was launching the Art as Therapy exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria. NGV is the first of three international galleries to implement a program based on the Art as Therapy philosophy developed by de Botton and fellow philosopher John Armstrong.

Art as Therapy argues that art should be scripture for the secular age, used to help people ‘live and die better’. They say the right art can rebalance us, addressing our needs for inspiration, consolation, hope and good memories, alleviating anxiety and improving relationships.

De Botton challenges galleries to caption and organise art to meet the psychological needs of viewers rather than simply by dates and materials. ‘No one’s ever had problem that’s been solved by 18th Century Art, 19th Century art, European art. These are not categories of the heart. They are categories of the index system of curators who have grown up in a certain kind of educational path,’ he said.Instead the philosophers envisage galleries of love or comfort, rooms where works are placed together to invoke feeling of gratitude or pride, to remind us how we felt in the first flush of love or console us that our grief or anger will not last forever.

The tours he and Armstrong have developed for the NGV collection, and for collections in the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, and the Art Gallery of Ontario, are the first in the world to implement the approach.

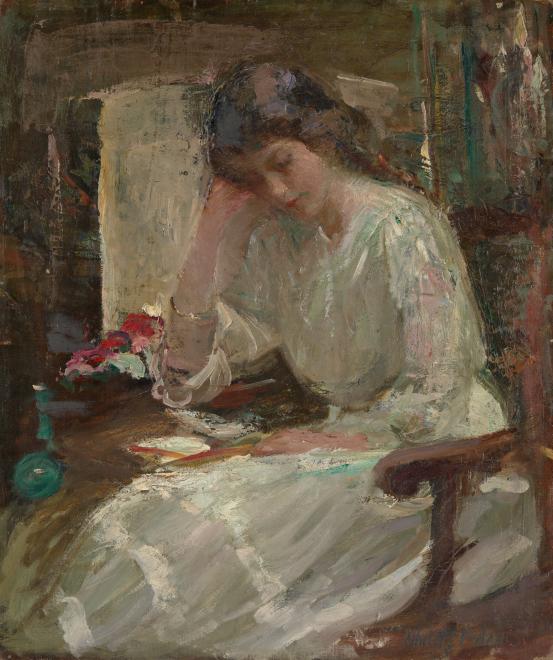

From the NGV collection, Girl Reading by Josephine Muntz Adams was chosen as a work which meets the human need to be reminded of good times, in this case an ordinary moment of serenity. ‘There is a lot of very dark stuff about being human, a lot of very sad things and one of the things we look to art to do is to remind us of the happy times.’

De Boton said museums were often uncomfortable with the fact that ‘pretty art’ is most popular. ‘It’s flowers in springs, it’s children in meadows, it’s sunny days and curators sometimes put their heads in their hands and go “Are people stupid?” because there’s a great suspicion amongst elite curators against prettiness. Prettiness is seen as slightly stupid because the fear is that if you like something very pretty, you have forgotten Syria.’

He believes we should not panic about sentimentality. ‘It’s precisely because most of us are on the edge, not of over-optimism but in fact of despair, clinical depression, that we need art to pull us in a more hopeful direction.’

At the same time, dark works also meet strong human needs. The Derision of Christ, a medieval sculpture by Marc Antoine du Ry also in the NGV collection, is cited by de Botton as a work that can relieve the viewer of the superficial cheerfulness of everyday life. ‘All of us go through very dark moments …that’s another function of art to act as a mirror and a confirmation of the legitimacy of our sorrows.

‘The Derision of Christ shows Christ at the lowest point. You don’t have to be a Christian to realise that what is going on there is a portrait of sadness and that all of us have been there every now and then and we will be back there again. This is a place that is carved out for human nature to visit every now and then. It’s terribly helpful if art shows us that this is normal.’

De Botton is in Australia to launch a Melbourne branch of The School of Life, the first branch outside his UK home. The School will offer courses, therapy and conversations using culture to help develop emotional intelligence and improve everyday lives. It aims to make art something we use to deal with ordinary stresses such as anxiety or marital disharmony and with major life challenges like the search for love and the fear of death.

He believes we should deliberately seek out images that meet our individual needs, not just in galleries but through reproductions we can live with. He imagines a form of art therapy where a therapist would listen to a person’s needs and problems and suggest a selection of works that would help.

The Art as Therapy approach is a return to a view of art as a replacement for religion that first surfaced in the mid-19th Century when galleries first received public funding and university humanity departments were founded. But de Botton said the cold academic approach of the modern museum was a long way from being a secular cathedral that addressed human needs.

Art as Therapy is the beginning of a movement to change that.

Art as Therapy Exhibition

NGV International

28 March to late September, 2014

Art as Therapy Guided Tours with The School of Life Melbourne Faculty

Saturdays, 3pm on 5 April, 12 April, 26 April, 10 May, 24 May

NGV International, beginning at the Information Desk

Bookings essential at http://www.theschooloflife.com.au