Hi Megan. Can you tell us a bit about who you are and what you do?

Sure. I’ve always been torn between the two things I like doing most, both writing and visual art.

I consistently got the message as a young person, as a child, that it was really nice to do visual art but it wasn’t a job. Because of that, I naturally leant into the more literary side, and that started out as an attempt to get a law degree. But I very soon realised that just was not me at all. So then I gravitated towards journalism at RMIT. But as soon as I graduated from journalism, I also knew that my calling was not to stick a microphone in a politician’s face. It just wasn’t what I was into.

Marieke Hardy was writing for Neighbours at that time. We’d become friends in the late 90s and were working on other creative projects together and she was the one who suggested I try my hand at writing for TV. If she hadn’t given me that gentle shove towards TV, I probably wouldn’t have gravitated there. I wasn’t a huge TV watcher, and I didn’t realise how much I loved it till I got in there.

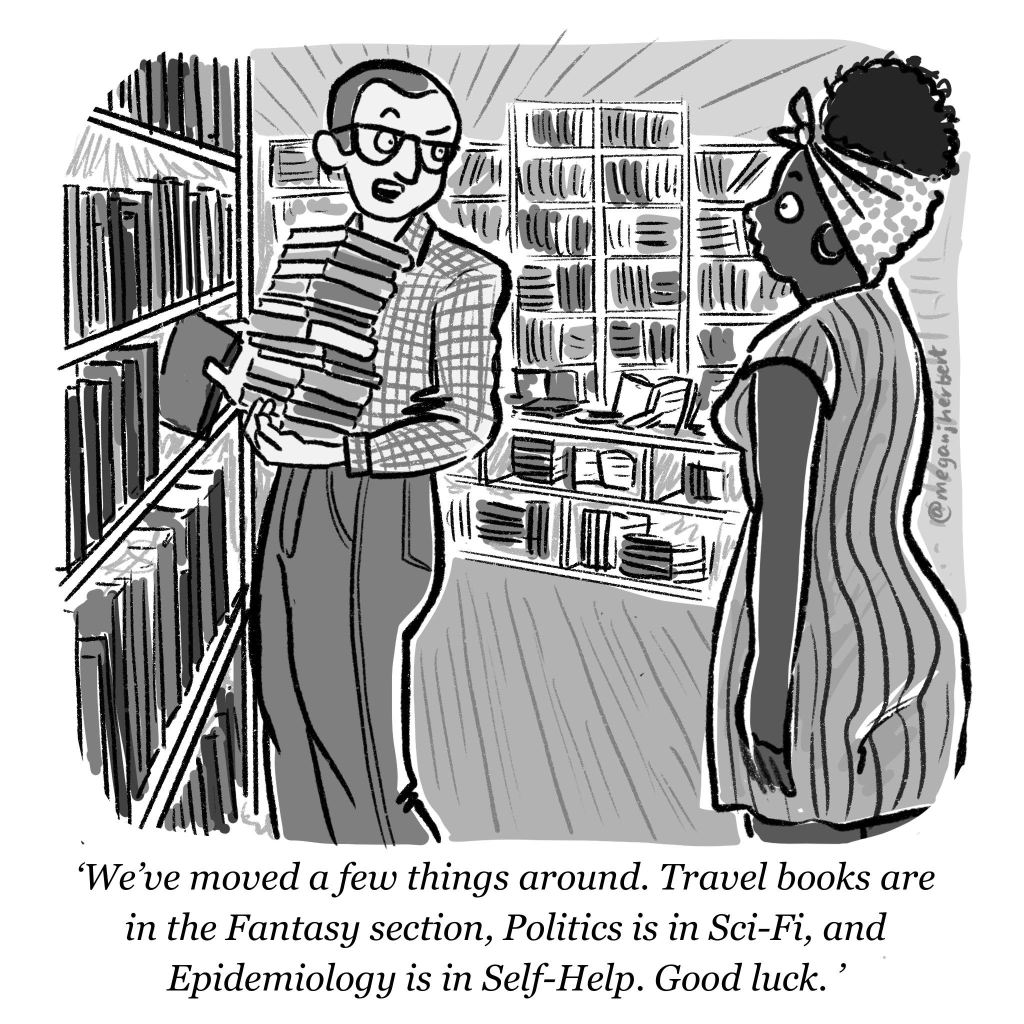

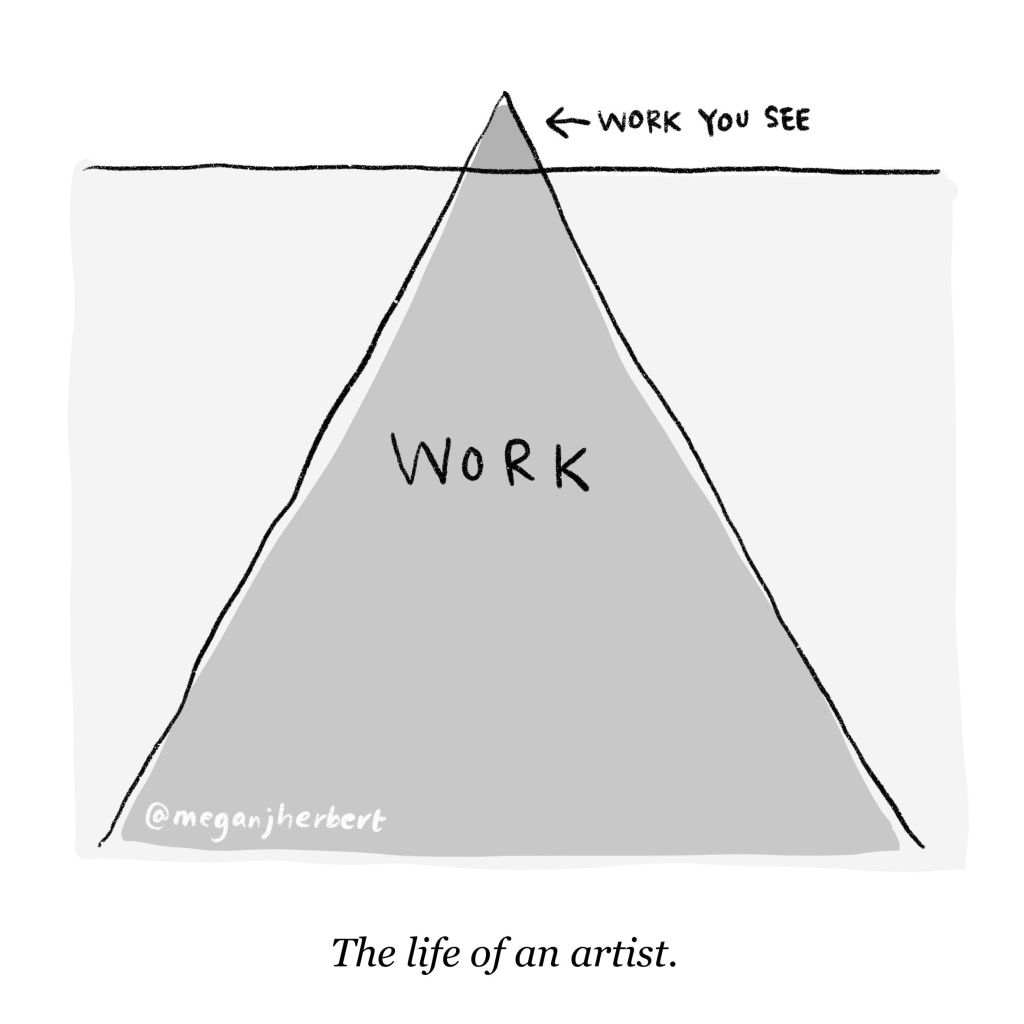

It’s taken many years for me to give visual art legitimacy and to feel that it’s actually a job, even though I’m equally interested in that and equally skilled at it. But I now have a good balance both those areas. I’m a political cartoonist for The Age, which obviously has both a visual and written component. And I also write and illustrate children’s books – a perfect marriage of the two things I do.

Read: How to succeed in Generation Slashie

I do get quite a lot of work which is pure illustration, and I’m still doing some stuff in the TV and film camp as well. But I think I’m happiest when I’m working in both skills at the same time.

It feels like it’s taken me so long to get there because of that messaging I got as a young person, you know – don’t try to earn money doing art. It takes a long time to break down those things we’re told.

You’ve done a lot of work on Neighbours over the years …

It was 2001 I started there. There was a position on the story team opening up, for an in-house writer. I had no experience whatsoever but Marieke said: ‘I think you’d be really good at this. you should just apply.’

They liked my writing samples enough that I got an audition of sorts. At that time, they would bring the people they were interested in into the story room for about a week, and you just had to participate. That was your interview. In a story room you have to have a good mix of people who are open, who don’t kill other people’s ideas, and who keep the creativity going. They can’t see that in a standard interview, so the solution was to be there in the mix as a storylines to see if you gelled.

They gave me a job as a script coordinator. That was the beginning of my life at Neighbours, and over the course of 21 years I’ve been on again off again in every role in the script department, including stints as story producer and script producer. I wrote my last script for them in March, and now the show’s ending, which is really strange. It’s been a huge part of my life.

Are you surprised it’s ending?

I’ve spent a lot of years living overseas, and every time I’ve left the country I’d voluntarily step away from the script roster because I believe you really have to be here and have your head in the show to be able to submit good work. And honestly, every time I came back, I was kind of amazed that it was still going. That’s not a reflection on the quality of the show – it’s just because the landscape of television has changed so much and audiences have changed and what they want is different.

I had an eye-opening moment last year when I did a school visit for my children’s book. I mentioned Neighbours and there was just a roomful of blank faces. These were nine-year-olds. None of them had any clue what a soap opera was. The teachers knew about Neighbours but none of the kids did. It was something that every nine-year-old in the country knew and loved when I was growing up.

Read: Axing Neighbours will be a screen industry blow

So I’ve always been amazed that they kept going as long as they did, given all of that. And I think it speaks to the quality of the work and the fact that they were producing such great actors and writers – what an amazing breeding ground it’s been. But it did feel like eventually that changed landscape would catch up with the show and not through any fault of its own. It’s just that the world’s moved on.

So why did it last so long?

It’s a testament to the incredible scheduling power of the production team. It’s just staggering what they pull off on a weekly basis. In the last couple of years, they went back to doing five episodes a week, which is hilarious to say, but for a period there they were shooting, writing and directing six episodes a week. That’s just nuts. I mean, you surely couldn’t find another show in the world doing that. Especially not drama. It’s mind-boggling.

Anyone who got to experience working on that show is really lucky because the skills we all learned there will hold us in good stead in any part of the world, on any show.

A lot of people love to make fun of Neighbours or look down their noses at it. But if you look at all the pressures on it, from restrictions through to budgets and everything else, the content that actually comes out of the wash at the end is remarkable. It really is. And I think you don’t get that if you don’t have top talent working on it.

When I first started working there, if you were at a pub in Australia and somebody asked you what you did for a job, and you mentioned Neighbours, they’d just say, ‘Oh my god, I hate that show’. In the UK, it was the polar opposite – people were lining up to buy you a drink and wanted to know everything about it.

How did you become a political cartoonist?

It started in one of the Melbourne lockdowns. I was living in Amsterdam when Covid kicked off, and had planned to come home in 2020. But then there was a bit of a spanner in the works with Australia shutting its borders.

When I got back here, finally, I made a commitment to do a 100-days project, because I just had this burning desire to break into the New Yorker as a cartoonist – and I’m still working on that, I haven’t been accepted yet, although I still submit cartoons regularly.

Read: Essential guide to making it as an independent creative

But in doing that 100-days project, I really learned the form of cartooning, and have been in touch with all these people who do it very well. I feel like I’m in the student phase right now, where I’m just absorbing as much as I can, and trying to do it frequently enough that I build up my muscles. And that led to the job at The Age and Sydney Morning Herald, where my work was just noticed by the right people at a time when they were looking for somebody new. So again, it’s one of those fortuitous things that, if you do the work, and put it out there, sometimes the right people will see it.

Can you explain a bit more about the 100-days project? What does that involve?

It’s quite a common technique in the visual art world – a lot of illustrators do it when they’re either trying to get noticed or develop their skills in a certain area. And it usually involves doing something you want to be paid for but are not being paid for currently. You’re committing to no-one but yourself, and to anyone who’s following you on your Instagram, I suppose, to producing something every single day for 100 days without a break.

The act of committing to that does all sorts of things. It strengthens your muscles and sharpens your skills in that area. And because people come to rely on you doing it every day, it draws people to see your work, so it’s just more likely that you’ll be noticed for it. It’s a crazy commitment, with hundreds of hours of free work, essentially. But I see it as just putting in your hours, frankly, the same as if you’re an athlete doing your training.

And you also write and illustrate children’s books?

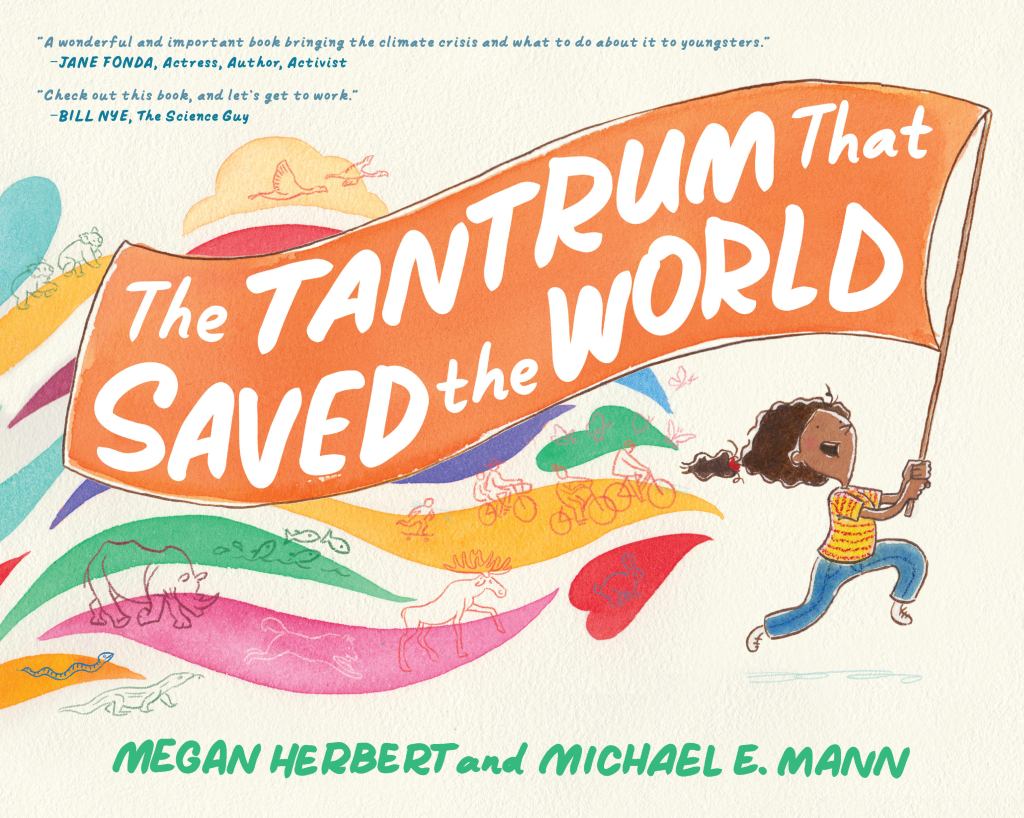

Yes, well, so far, I’ve only had one, fully written and illustrated, called The Tantrum That Saved the World, that’s published and out there. But I was illustrating other people’s various books, not all children’s books, for a few years before that. And I do want to write more children’s books but they take time. Another thing I’m working on slowly in the background is a graphic novel. But these are things that just bubble away …

What advice would you give someone trying to get into scriptwriting (or indeed cartoning or illustrating)?

We’re living in this fantastic time where you can do anything you actually want to do. The tools are there and they’re affordable, so you can make your own short films, you can put out an illustration on Instagram every day, or whatever your thing is.

There are a couple of concepts that I’ve latched on to in my own creative development because I listen to a lot of podcasts or read a lot of books about keeping motivated and how to break through and all those things.

There’s the 100-Days Projects. But there’s also ‘writing on stage’. It’s a concept that came up in the stand-up comedy world, which I think be applied to any creative art. Comedians like like Marc Maron do it a lot, where you’ve got some loose ideas and you just take them up and workshop them during a set. You see what works and what doesn’t, so you’re honing and honing and honing.

The 100-days project that I did was exactly the same thing, because I would see which cartoons people connected with in which they just went straight through to the keeper. Some of them went ridiculously viral and I was like, ‘Oh, wow, that’s really interesting’.

You try to analyse why, and you get better and better at that because you see the patterns. And the same thing could be said for anything that you put out there into the world.

The other good thing about that kind of approach is it makes the negative feelings about rejection really minimal because you’re putting so much out that nothing is your baby – everything is just done in the moment. Not everything you put out there is going to be perfect or even great but it just keeps getting better because you’re doing it.

So I think if somebody wants to write scripts, in whatever format, or they want to make films or direct films, I would always say just make a thing, anything, and do it regularly. Don’t sit there obsessing over one project and not talking about it and keeping it in your in a folder on your computer. You’re better to make 100 average projects because you’re going to learn something and get better on every single one.

You’ve got to just let go of the perfectionist vibe and just put it out there because it’s actually a bit arrogant to assume you know how everyone’s going to react to your work. Often the ones that take you only a fraction of time or that you dash off are the ones that totally resonate with people. If you sit there saying, ‘Well, I’m not going to put it out because it’s terrible’ that’s a fallacy because it’s such a subjective thing. You have no idea what other people are going to think about what you make.

That reminds me of the Ira Glass clip where he talks about the gap …

Between your taste and your ability?

Exactly, yeah – that you have to just keep going because waiting until it’s right isn’t going to work, because it only becomes right by doing it.

Yeah, right. Another one of my regular listens is a podcast called Creative Pep Talk with Andy J Pizza. He’s an illustrator and the podcast was initially geared towards the visual arts, but all the concepts he talks about could apply to any creative field.

He talks about a lot of the things we’re discussing now, and the bottom line is: it’s all just about doing it every day, working out what thing you want to be paid for, and just doing it before anyone’s paying you. Then someone will see it, and they’ll pay you. You’ll get the job because you’re already doing it. No-one has to trust that you can do it because you are doing it, they can see it.

In an ideal world, would you focus on one of the skills that you have – or do you prefer to have a portfolio approach where you’re doing a bit of everything?

I used to torture myself with that question. And I always thought I was doing terribly in both things because I didn’t focus on one. And that was all part of my learning process, because I realised each different skill was informing the others. Now I’m finding the place where I’m absolutely happiest is in cartooning because it uses all the storytelling skills I’ve learned in TV and film writing. It uses all the visual narrative and storytelling skills I’ve learned in making kids books, and it can reach people on an emotional level about important issues.

I don’t want to just make pretty pictures or write stories that don’t have an effect. I like to actually try and change minds, influence people’s thinking or at least make them open their mind a bit more to something they hadn’t considered before. So cartooning feels the closest thing to achieving that goal.

The only the only downside is that I often feel like I don’t have enough time because I’m pursuing writing goals, illustrating goals and the combination at the same time. So I often wish there was an extra person – another me. But apart from that, I don’t feel like I need to specialise anymore.

Follow Megan Herbert on Instagram, Twitter, Medium and Facebook. Visit Megan’s website.

_Encounters-in-Reflection_Gallery3BPhoto-by-Anpis-Wang-e1745414770771.jpg?w=280)