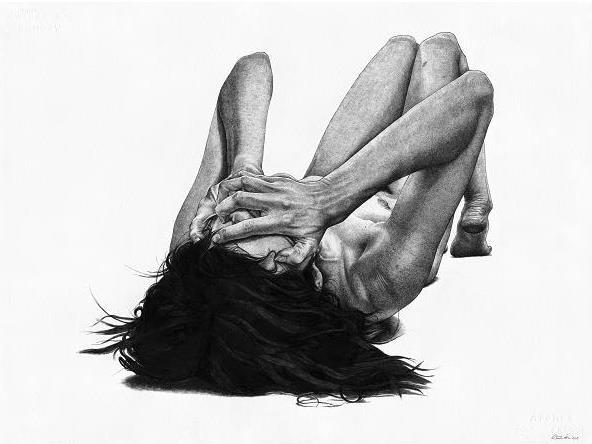

Untitled 2015, Lily Mae Martin

It is a rare artist who has never received negative feedback on their work, whether from teachers, critics or the public. While some brave folk use criticism as inspiration to keep going, others might be tempted crawl into a pillow fort and wallow, or take up accounting and never pick up a paintbrush again.

If we are constantly feeling pressure from critics, real or imaginary, we can’t be free in expressing ourselves. We won’t invest ourselves emotionally in our work, start to obsess about every potential mistake, and even self-sabotage. It can get to the point when an artist or writer is so riddled with self-doubt that they become creatively blocked and are unable to produce any work.

There are two kinds of criticism: criticism from others and self-criticism. But they are far from discrete entities. Eventually, the criticism from others can become self-generating as we internalise it over time. Then we can become our own worst critics, inhibiting our creativity. Finding a way to deal with feedback, both internal and external, is an important part of growing and developing our creativity.

Reviews: enemy or irrelevance?

There is no other field of work where there is an entire profession of people paid to hold your work up to scrutiny. Professional reviewers, especially those working for major newspapers, used to have the power to make or break a work.

While prominent artists like to claim not to read the reviews, it takes more forbearance than most humans have not to sneak a look.

Fortunately for artists, the power of a single review has been dissipated by the growth of online and social media. Niche sites (including ArtsHub) provide a wider range of voices and the public has its vote on Facebook or Instagram.

Ali Alizadeh is a poet, novelist, playwright, and a critic himself. His work is divisive and has elicited strong responses, ranging from “eclectic, passionate and compelling” and “a talent to watch” to “headache provoking” and “a shame”.

He believes reviews matter much less than they used to. ‘People don’t care about reviews anymore,’ he said. ‘It’s been extraordinary to see the decline of the rapture and aura of reviews. Critics can’t make or break a performance or piece of writing anymore.

‘I once had my work reviewed in a feature for The Age. There was a big colour photo and I thought I’d made it and would be able to retire, but it led to no extra sales of my book. And I once received a dreadful review for a play, one star, and it still sold out every night. People don’t care. What matters is how one feels about the work they have made

‘Historically, reviews reflected the rise of the bourgeois middle class, who thought they knew better than the peasants. Some reviewers are failed writers, so there is a bit of bitterness and nastiness there. It’s all about the egos of the reviewers. Their opinions are masqueraded as reviews.

‘Now, consumers are empowered. People are more educated and can go to a bookstore or to the movies and make up their own minds,’ said Alizadeh.

Opera Australia’s principal artist Adrian Tamburini agrees. ‘Criticism is only one person’s opinion. No matter how much weight you put on what they have to say about you, it is only one assessment made at one moment in time. Take what they have to say and use it to be a better performer the next time. Surround yourself with people you trust and listen openly to their criticism: that is the best criticism of all. People who you trust will tell you your shortcomings as well as your strengths in a constructive and caring way. Through this feedback you will be better armed to improve your performance each and every time.’

Read: No stars for five star reviewing

On the other hand, information overload and the ever-increasing range of options for cultural activity means the importance of reviews in helping audiences find what’s out there remains. Skilled critics try to convey not so much whether they like or dislike a work but what its interest and value is to potential audiences, serving the paying public with a limited dollar to spend rather than the artist.

Read: In defence of star ratings

Beyond the sting

Writer and playwright David Burton has recently released his memoir How to be Happy. He feels he has dodged many critique bullets. ‘I’m white and I’m male, so I don’t put up with anything like what I see other peers of mine go through when it comes to vitriol’, said Burton.

‘But overall, criticism can be helpful. In an ideal world, critique comes from an incredibly articulate, smart source who can make your writing better. Other times, the intention of the critique is great, but the source isn’t so articulate, and it may come out clumsily. In this scenario, I do my best to overcome the sting of pain to try and get clear about what someone actually intended when they offered a critique.

‘Other times, I’m able to look at a critique and realise the reader, reviewer, colleague or audience member just flat out didn’t get what I was trying to do. I feel angry, I get upset, I feel hurt, I feel vulnerable…and then I try and shake it off. I try to not let it bother me for more than half a day.’

Burton still gets bothered by poor reviews. ‘Of course. It’s crap. It’s also inevitable. I’ve vowed to not read reviews. But we’ll see how long that lasts.’

His advice is to use the critique where possible. ‘Firstly, ignore it, if you can. Don’t go into the dungeon. Secondly, there’s a difference between helpful critique and opinion. Someone’s opinion is none of your business. It’s theirs, it has nothing to do with you. Critique, if offered from a trusted colleague or professional before your show opens or before your book is published, can be a game-changer.’

Read: How to give better feedback

Snark is not feedback

Lily Mae Martin is an artist whose current exhibition explores striking female nudes. She has learned to be okay with not everyone liking her subject matter. ‘When I was younger my response was a little more emotional than it is now, it was confronting. Back then, there were more comments about my technique rather than my subject matter and I guess in a way I knew I was lacking. I’m someone who likes to turn things around for the better so I spent some time identifying my technical issues and addressed them until I felt they were resolved it in some way. So even though people flat out do not like my work and subject matter – well, that’s subjective and I’m pretty okay with that.’

‘I’ve had plenty of negative feedback, but I guess it depends on what I think the person’s intent is. Are they being constructive? Are they being dismissive? The dismissive thing happens a fair bit and I often wonder of this happens because I am a woman. When people are flat out nasty – which has happened – then I don’t take that on. Sometimes snark is dressed as feedback and there’s no place for that.

‘Look at the person giving you advice – do you respect what they do? It’s great to try and step out of yourself and analyse your own work critically (as much as you can) and consider other ideas. But if it doesn’t resonate with you, that’s okay, you don’t have to take it all on. You don’t really owe anyone that. ‘

Read: Why we need dance criticism

Tamburini tries not to let criticism affect his performance. ‘Of course I get upset, I wouldn’t be human if I didn’t. But you have to move on or else you’d never get back on stage again. No one can give me worse criticism than I give myself, so I am never surprised when I receive negative feedback.

‘Criticism is all part and parcel of a performer’s life. Anyone who puts their work in a public forum has to be prepared to receive both positive and negative criticism. I learnt very early on not to take any criticism to heart, but to use it to improve as an artist and a performer. Getting wrapped up in what other people think about you can be crippling for performers.’

Your toughest critic

Setting your own standards and not relying on other’s judgement can be helpful but it can also make you vulnerable to expecting too much of yourself or beating yourself up when things go wrong.

Principal cellist with the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra David Berlin told ArtsHub, ‘It is disappointing to receive negative feedback in news media. The credentials of the critic are usually unknown, so you have the absurd situation of a negative opinion by an unknown person being taken in by a potentially vast readership. My advice to other musicians is to consider seriously the advice from those you respect and develop a thick skin to those who are unknown to you or who’s work you don’t admire.’

Tamburin, who is currently performing in Carmen and Cosi fan tutte at the Sydney Opera House, has had his share of ‘fails’but the results have not always been as he expected.

‘The perfect example is an audition I gave which, in my opinion, was worse than any street busker’s singing I had ever heard. I was so upset with myself and plunged into a dark depression for a long time. But, not only did the audition panel look past the bad parts of the audition, they heard a redeeming quality in my voice, had taken into account my experience and decided to give me the job anyway. So my ‘failed audition’ was in fact a successful audition.’