Image via Shutterstock

Whether writing for an orchestra, an ensemble, or for the theatre, film or television, the composer’s art conveys emotion through music – enhancing existing drama and conjuring the sublime.

But how does one start as a composer – is it the sort of career you stumble into, or a calling felt from an early age?

‘In hindsight, my love for composition was sown when I was quite young, not that I realised it at the time,’ said Western Sydney’s Holly Harrison, one of two Australians composers commissioned for Musica Viva’s 2018 Melbourne International Chamber Music Competition.

‘Some of my most treasured musical memories are from making my own music. When I was ten, I played trumpet in a semi-improvised experimental rock band for a local theatre production, and developed a love of improvisation and strange sounds,’ she told ArtsHub.

‘My first real “piece” was for an assignment in Year Nine, where I took great pleasure in recording two duelling descant recorders, trumpet, keyboard bass, drums, and euphonium (on loan from my older brother!) in my lounge room, with lots of reverb.’

Harrison played drums and trumpet in a variety of bands growing up, as well as forming rock, metal, and punk bands. After finishing secondary school she studied a Bachelor of Music at Western Sydney University, which reignited her interest in improvisation and composition.

‘I had a fabulous time, studying an eclectic mix of music, from plainchant to Stravinsky to Nirvana, and received wonderful support and encouragement from the teaching staff. From here, I pursued an Honours year, and then a Doctor of Creative Arts (still at WSU) with Bruce Crossman and John Encarnacao. At that stage, it’s fair to say that I had aspirations to be a composer, though I wasn’t sure how likely it was, or how to go about making it a reality,’ Harrison said.

Read: Career spotlight: Conductor

Melbourne-based Julian Yu is Composer-in-Residence at the forthcoming Australian Festival of Chamber Music, held in Townsville in mid-winter.

‘I never set out to become a composer and don’t consider it a career at all – it’s just something that I love to do,’ Yu said. ‘It evolved naturally as a result of a series of nurturing environments and happy coincidences.’

Born and raised in a close-knit community of cotton factory workers and their families in Beijing, Yu credits a childhood teacher as a significant influence on his life.

‘In primary school we had a great music teacher, and when I was about 11, I joined the school’s “propaganda team” and we used to make trips to the countryside to perform Beijing opera to the peasants. My main instruments were the erhu and jinghu two-string fiddles, but we were just a group of friends all performing together and we’d swap instruments and mess around, so I got to try out a lot of other Chinese instruments – yueqin, liuqin, qinqin, bamboo flute, gongs, drums and so on. I used to compose music under the desk during maths lessons for us to play, and in my first year of high school I wrote a one-act Beijing opera that we performed,’ he explained.

‘When I was 15 my music teacher heard that the Central Conservatory of Music was recruiting new students for the first time since the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, and accompanied me to the audition. Instead of auditioning as an erhu player, which was the obvious choice, he had the bright idea that I could try for the Composition Department instead. Oh my God! All the other contestants were a lot older than me, could read Western notation, and were proficient on Western instruments. And there was me in my ragged trousers with my erhu, jinghu and numeric folk notation! But luckily on the panel there happened to be one older teacher who had been the principal arranger for China’s number one Beijing opera singer Mei Lanfang, and he really liked my numeric Beijing opera score.

‘I never set out to become a composer and don’t consider it a career at all – it’s just something that I love to do.’

‘My four years of study at the Central Conservatory, based on the Russian model, gave me a thorough grounding in the tools of composition, namely harmony, counterpoint and orchestration, and after graduation I was asked to stay on as a teacher of harmony. But our musical environment was very limited because of the recent Cultural Revolution, and I still had no exposure to most of the Western music repertoire, let alone atonal music, jazz and so on. So I was lucky to be selected by the Conservatory to study composition at the Tokyo College of Music for 18 months with two of Japan’s top composers, who opened my eyes to a whole new musical world as we delved into the question of how to inherit one’s own cultural tradition.

‘That was the beginning of my development into the composer that I am today. After my move to Australia, two scholarships for further study enabled me to continue composing, I was invited to Tanglewood and received recognition from Leonard Bernstein, Hans Werner Henze and Oliver Knussen, and one thing led to another,’ Yu said.

Composer, saxophonist, arranger and director Rafael Karlen is a graduate of the Queensland Conservatorium of Music and the University of York in England. He was recently announced as the 2018 Composer-in-Residence at the prestigious Peggy Glanville-Hicks House in Sydney.

‘I have composed and enjoyed studying scores/music for a very long time so [becoming a composer] was a gradual progression for me,’ Karlen said.

‘I was lucky that Tony Hobbs, my saxophone teacher at university, was not only a beautiful player but also a serious jazz writer and arranger so I was able to bring in pieces that I was writing and he could offer options, advice and recommend new things to study.

‘In jazz [and] improvised music it is very common to write pieces for your own performance projects which makes it a lot easier to fall into composing and to learn on the job,’ he said.

Formal training vs on the job

In terms of education, ‘Everything is helpful,’ Karlen said. ‘Formal and informal lessons, independent study and learning on the job are all really useful and complimentary avenues for learning how to create music. Finding people who are doing what you are interested in and asking them things that you would like to learn about can help to keep things moving forward.

‘I have had many one-off lessons with different composers but I do think that composition is a difficult thing to teach,’ he continued.’ Although I’ve been very fortunate to have interacted with many wonderful composers and arrangers who have shared really valuable concepts and techniques, most of my learning has been by myself through studying scores and recordings and writing pieces.’

Harrison noted that training and education options varies, depending on both the individual concerned and the genre they’re working in.

‘For new music composers, most formal training is through University, where you study closely with a mentor. In addition to this, there are a number of programs in Australia and abroad which mentor composers and provide a type of “on the job” training. The first that springs to mind is the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s Cybec Program, which commissions new works by emerging composers, mentored by an established Australian composer (I was paired with Matthew Hindson). I’ve also received mentorship through festivals and residencies overseas, including Richard Ayres and Martijn Padding in the Netherlands, and Nico Muhly and Kevin Puts in the U.S.. Here in Sydney, Ensemble Offspring run the Hatched Academy, which mentors both performers and composers in creating new work,’ she said.

‘Informal learning is just as important too. You can learn a lot from composer friends over a drink! I’m learning every day, especially from performers. Ultimately, the performer knows more about their instrument than you do, and it’s great to absorb that new knowledge,’ said Harrison.

Composer Holly Harrison; image via www.hollyharrison.net. Photo credit: Steve Broadbent.

Yu said: ‘There are three phases in the development of a composer: first, composition for the love of it and the discovery of natural talent; second, rigorous hard work and the accumulation of experience; and third, the application of highly refined intuition that can’t be taught, but that differentiates great music from good music.

‘Some composers work hard but lack talent, or don’t receive adequate guidance, or they are highly talented but don’t put in the hard work, so they stay at or below level 1. Many others are talented and study hard, so they reach level 2 without difficulty. But level 3 belongs to the exceptional composers, whose music is imbued with that je ne sais quoi, the nuance that speaks directly to the heart. Some level 3 composers are not formally trained at all but learn through practice – for example, Toru Takemitsu and my teacher Joji Yuasa. But for most, training at a conservatorium is the easiest way to gain the required skills and experience to become a composer.

He continued: ‘For composition many skills are required, and they do not rely solely on training. Chinese composer Yuankai Bao sums it up beautifully when he teaches his students that:

‘Writing a melody requires natural talent;

‘Harmonisation requires feeling;

‘Orchestration requires experience; and

‘Counterpoint requires craftsmanship.’

A day in the life

‘I am lucky that my working days are flexible, because my job is my hobby,’ Yu explained.

‘I prefer to work at home in my music room, and for me, every day is a “working day,” that is, a hobby day! I usually start composing before breakfast, at about 7.00am. Some days I compose more, other days less, and I can start and stop at any time. Initially I note my ideas down on paper, perhaps trying them out on the piano, and then I commit them to the computer, play them back and fiddle round with them. My breaks are spent shopping, cooking, bike riding, napping, listening to music, playing the piano, meeting friends and so on. I usually go to bed at about 11.00pm, but if inspired I sometimes continue writing into the early hours of the morning.’

In Harrison’s case, her day to day activities can vary quite widely, depending on the time of year.

‘At the moment, I teach a few days a week at MLC School, Western Sydney University, and Caroline Chisholm College. As it’s school holidays, this week I’m workshopping my two latest pieces with performers. The first is my children’s work, The Mad Hatter’s Tea-Party, for Canberra International Music Festival, and the second is a new sextet for Ensemble Offspring, still in draft stage. In between editing these scores, I’ll be working on a piece for the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra,’ she said.

‘For a composing day, I like to improvise and record soundbites, before putting them into notated form (in Sibelius) and then experiment and refine the idea. It can be quick or slow-going, depending on the piece. There are also days of editing and engraving the score, proof-reading, and extracting the players’ parts. And then there are performance days too, which are extra special!’

Composer and saxophonist Rafael Karlen. Image via www.rafaelkarlen.com.

Karlen’s routine has changed significantly this year, thanks to his becoming a Prelude Composer Resident in the Peggy Glanville-Hicks House.

‘Previously my work days would also include balancing gigs/rehearsals, lecturing/teaching commitments and some ensemble directing work,’ he said.

‘I’m not very good with routines but my days generally include the following: studying recordings and scores; a warm up on saxophone; generating ideas on piano and trying to connect my ear; spending time thinking about what I would like the piece to do or where it could go; and composing or arranging for the most urgent project.

‘Unfortunately a lot of time is spent working on administration i.e. emails, planning and setting up projects, calls, applications etc.’

He also reads, ‘mostly non-fiction books as I find that this prompts me to react and connect with something and to keep life in perspective. This also helps to trigger ideas for things that I would like to try and include or things to draw inspiration from,’ Karlen said, before adding that ‘tasty coffee,’ is also a key element of his daily routine.

Career lowlights and highlights

‘There have been a few lowlights but having to work at a café directly across from the Conservatorium, serving coffee to my old students and teachers after recently returning from a prestigious fellowship and Masters program in Europe was particularly sobering. It was a useful reality check,’ Karlen explained.

‘I am lucky in that I have a few very special highlights which include being awarded the 2018 Prelude Residency at the Peggy Glanville-Hicks House in Sydney to write music for 12 months; traveling around the world for 10 weeks to meet with many of my musical heroes as part of a Winston Churchill Memorial Fellowship; and composing, performing and conducting a concert of my music for a QSO chamber orchestra as part of their QSO Current (now WAVE) series.’

Another highlight was being Musical Director for the Queensland Music Festival Yarrabah Band Festival, at a Finale Concert with Archie Roach, Katie Noonan, Montaigne, Shellie Morris and local community musicians. ‘This was a very special experience,’ Karlen said.

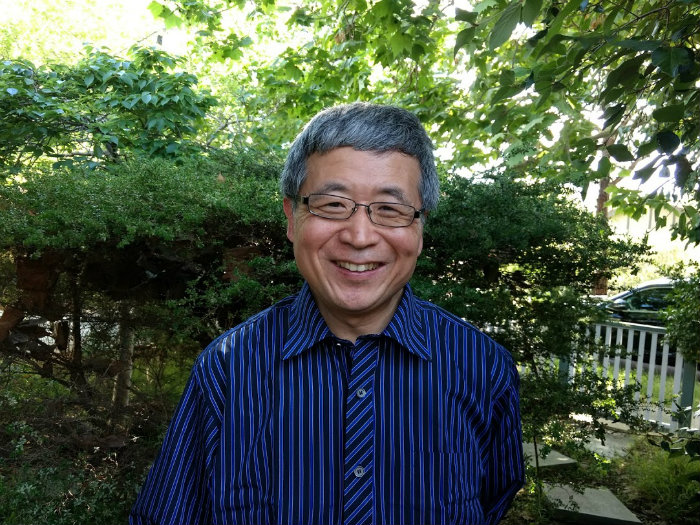

Melbourne-based composer Julian Yu; image supplied.

Yu described one particularly sobering moment in his career, which occurred soon after he immigrated to Australia in 1985.

‘One of the first things I did was to visit the Commonwealth Employment Service. The officer asked me what my profession was and I told him I was a composer. He told me curtly that they didn’t have any jobs for composers, and promptly showed me the door! At the time I felt a little crestfallen, but I soon found a job as a casual kitchenhand,’ he said.

Conversely, meeting Leonard Bernstein was perhaps the biggest thrill of Yu’s career.

‘It came about when I was selected to study with Oliver Knussen at the 1988 Melbourne Summer Music School; Knussen recommended me for a scholarship to take part in the Tanglewood Music Centre’s Composition Fellowship Program for that year, and I won the Koussevitzky Tanglewood Composition Prize,’ he explained.

‘All the composer fellows were invited to show Bernstein a piece they had written. Some of the compositions he threw dismissively on the floor without a further glance, some earned a nod of interest – but when he got to mine (an orchestral piece called Wu-Yu), he was heard to mumble, “Fucking genius!” He had dinner with us and I had to cook a stir-fry dish, so after that he called me “Stir-Fry”. Considering his greatness, I was surprised at how easy he was to get along with, but later I came to realise that many great people are actually very approachable. I remember that he gave each of us a wet kiss!’

Yu also shared a career lowlight, and what he learned from it, with ArtsHub.

‘Perhaps my biggest disappointment came after the performance in 2000 of my orchestral piece Not a Stream but an Ocean, commissioned by the BBC Proms. I had worked really hard on it and thought it was a great piece, but the audience and critics seemed cool and the new head of Universal Edition (London) Ltd, who had already published many of my works, was strangely silent. After that UE seemed to lose interest in me, and for a long time they did not publish anything more of mine. Although nobody said anything, I feel sure it was because of that piece. Perhaps I took the London Proms commission too seriously and was too conscientious. I often find that my best pieces are written quickly with inspiration or enjoyment, rather than laboriously in pursuit of technical perfection,’ he said thoughtfully.

Read: From arts publicist to stage manager: 22 careers explained

Harrison was also happy to share some of his career highlights and lowlights.

‘Without blowing my own trumpet too much, a real highlight so far was my work Cabbages and Kings receiving first place at the 2014 Young Composers Meeting, The Netherlands, with a jury chaired by one of my heroes, Louis Andriessen,’ she said.

‘This opened up a lot of new opportunities for me, including writing a series of works for Orkest de Ereprijs, and starting to gain some recognition here in Australia. A potential lowlight, in the same week, was failing to find middle C at the piano in a composition lesson with Martijn Padding….

‘Another highlight was touring nationally with Chicago group, Eighth Blackbird, as part of Musica Viva’s 2017 International Concert Season, and hearing my piece Lobster Tales and Turtle Soup performed in multiple cities,’ Harrison continued.

‘I’ve experienced my fair share of what you might call lowlights, which is all part of being an early career composer. There have been plenty of opportunities I’ve applied for and missed out on, or ideas that didn’t work, or hurtful comments and criticism, but that’s part of the process. In order to “go for it” and create something, you have to be open to that idea. If anything, minor setbacks have cemented for me that composing is what I really want to do.’

Advice for aspiring composers

Harrison’s advice for younger composers is to ‘write the music that you want to write, and develop your own voice and sense of self, while listening to feedback from mentors and performers’.

She adds: ‘This might seem like a difficult juggling act at times! If you don’t have ready access to performer friends, apply to programs, call for scores, and competitions which offer performance opportunities. Take the time to present your scores nicely, and listen to a wide variety of music.’

Karlen said: ‘I remember hearing that one of the keys to being a successful composer is to live a long time.

‘In the meantime, take confidence from the fact that there isn’t a clear path so everyone finds their own way to design their own life. Don’t expect that things will be very easy but if you know what you want to include in your life and you don’t lose sight of it, then you have more chance than most other people in achieving something that means something to you. Also, if you want something to happen, make it happen, don’t wait for someone else to give you ready-made opportunities.

‘Surviving by just doing what you want to be doing is rare. Everyone finds a way of balancing income with love projects. It is uncommon that they are the same thing. Realising that they may be different can add focus to what you really should be spending your time doing,’ Karlen continued.

‘Take things seriously but make sure that there is still time for fun along the way. I realised far later than I would have liked that we are allowed to enjoy making music, it is not something which is reserved only for the world’s finest musicians,’ he concluded.

The final word goes to Yu, who advised: ‘Treat composition as a hobby, not as a task, and then you will always enjoy it. If possible, say no to things that don’t inspire you.’

Holly Harrison’s genre-bending new work Balderdash can be heard at the Melbourne International Chamber Music Competition, running from 1-6 July. Visit https://musicaviva.com.au/comp/ for details.

Julian Yu is the Australian Festival of Chamber Music’s 2018 Composer-in-Residence. The festival runs from 27 July – 05 August in Townsville, QLD. Program details at https://www.afcm.com.au/.

Rafael Karlen is the 2018 Peggy Glanville-Hicks Composer-In-Residence. Learn more about his practice at https://www.rafaelkarlen.com/.