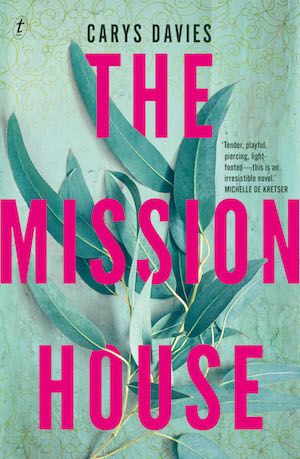

In Carys Davies’ The Mission House a melancholy and distinctly odd Englishman named Hilary Byrd wanders into an Indian hill-station in Southern India.

Here, Byrd finds fellow misfits in the Mission House where the Padre and his adopted daughter Priscilla live. There is also a driver named Jamshed, who ferries Byrd around the small town in his rickshaw. Jamshed takes a peculiar and specific interest in Byrd, partly based on the hope that the English tourist will provide him with several weeks of easy income. Jamshed has a nephew called Ravi who aspires to become a cowboy singer and is obsessed with buying a costume and a horse in order to fulfil his dream. There is also Miss Moreland, the Australian organist and Mr Page, the absent Canadian missionary, who play a small but not insignificant role in the narrative.

Byrd writes to his sister Wyn about his daily life in the Mission House, and it becomes apparent that all is not well in the life of Hilary Byrd. ‘The fact was, home by itself depressed him. Home made him ill.’ This idea of ‘home’ and ‘somewhere like home’ is present throughout the novel, as Byrd finds the remnants of British life in the hill station, as he notes that most people speak English, as he goes to church with the devout Indian priest and his daughter.

Contemporary India intrudes in the rising tide of nationalism and contemporary Britain lurks in the English garden and in the Padre’s observation that ‘They came for the weather, Mr Byrd – like you.’

While there is no doubt that an impressive amount of research has gone into the novel, echoes of the very colonialism Davies seeks to critique, manifest in her writing. Byrd, for instance, notices how dark Indians are. Has he never seen Indians in Britain? What is to be served by repeatedly noticing how dark people are? The Padre and his daughter are described as short and round and very dark, with Priscilla being repellingly dark. Which makes Byrd’s later change of heart, falling in love with this short, stumpy, deformed and dark person, a little hard to believe.

Then there is the naming of the rickshaw driver. The name ‘Jamshed’ is either Parsi or Muslim. Yet his brother is called Bipin, which is a Hindu name, and his nephew is called Ravi, another Hindu name. Details are important if a reader is to believe the writer knows nuance. Especially in a novel that seeks to highlight Hindu nationalism.

We are constantly reminded that India is hot and sticky and its people are short and dark and apparently consume lots of fryums. The Englishman is uncomfortable in the heat and suspicious of the multitudes that throng around him. He is a deeply unattractive man in appearance and thought, always putting himself first. Yet we are meant to believe he will make a heroic sacrifice for a (dark) girl he has suddenly fallen in love with and a man he has never met.

Helen Benedict observes, ‘It has to do with keeping faith with your readers. If you get something verifiable wrong, why should they believe you when you really are making things up? Research, factual accuracy, lays the base for plausible fiction, for it actually enables suspension of disbelief in readers by building their trust.’ For this reader, then, that suspension of disbelief did not eventuate.

3 stars out of 5 ★★★

The Mission House by Carys Davies

Publisher: Text Publishing

ISBN: 9781922330635

Format: Paperback

Categories: Fiction, International

Pages: 246

Release Date: August 2020

RRP: $29.99