Lisa Mansfield is a Time-Based Art Conservator at the Art Gallery of NSW in Sydney, Australia. Their work involves the conservation and restoration of technologies, both old and new, as well as other durational works, including video, audio, software-based art, choreography, performance and more.

Mansfield worked in the publishing industry for 20 years before taking a leap of faith into conservation, inspired by one particularly engaging conversation at a garage sale. But contrary to common belief that conservators need only work with objects, Mansfield tells ArtsHub that interpersonal skills, collaboration and building community are equally important on the job. Though they certainly do come across some interesting objects that need unique problem-solving along the way – ever wondered what it takes to maintain a gaming joystick for a gallery collection?

Here, Mansfield recounts the joys of their day-to-day role, the opportunities that exist within the field, the vital (and transferable) skills needed and what the profession may look like into the future.

In this article:

How would you describe what you do?

I look after artworks that are durational. These include film, video and audio works, installations using computer-based technologies, and choreographic and performative works.

Conservators steward contemporary and historic artworks through the present, so they are preserved and accessible to audiences for as long as possible. It’s a wonderfully varied job that includes research, preparing digital and physical works for display and loan, conservation documentation, collection maintenance and preservation storage tasks, and artwork treatments.

Fun fact: if you are backing up your mobile phone photos to three places you are also doing digital preservation.

How did you get into your career and is there one thing you wish you’d known before you started?

My neighbour was having a garage sale at the same time as I was moving house, so we had people wander into our yard looking through our things. One of them was an archeologist, and we started talking about her work in a museum – I was hooked. I had a BA in Fine Arts, so after 20-plus years as an art director in the publishing industry, I took a leap of faith that skills such as project management, ability to meet deadlines and creative thinking, would translate to a different field (they do).

The Master of Cultural Materials Conservation course at the University of Melbourne taught me about art from scientific/material and ethical perspectives, including the importance of artist intent.

One thing I realised along the way is that having a Master’s degree doesn’t automatically translate to steady employment. Volunteering, joining committees and being a member of the Australian Institute for the Conservation of Cultural Material (AICCM) helped me become part of the field. It’s making for a very interesting life four years on!

What do you look forward to the most currently as part of your role?

The artworks lighting up every morning is a highlight; seeing them in the empty spaces before the doors open is fabulous!

Also, the continual learning needed to care for complex artworks is fun. This week I was deep diving into software libraries and vintage security camera lenses; last week it was how to maintain a gaming joystick (hint: non-conductive ceramic grease).

Recently, I was part of a small team at the Art Gallery of New South Wales working on Precarious Movements, a collaborative research project with UNSW (University of NSW), Tate, MUMA (Monash University Museum of Art), NGV (National Gallery of Victoria) and PICA (Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts), focusing on the development, production, presentation and preservation of choreographic works in the museum context. Rewarding work with a few steep learning curves thrown in for good measure! (See previous ArtsHub article on this project here.)

What’s the most common misconception about being a Time-Based Art Conservator?

That it’s a behind-the-scenes career where you quietly get to fix artworks in the conservation lab (spoiler alert: it isn’t). It’s a people-centric job, from collaborating with colleagues and experts in allied fields to prepare, install and preserve artworks, to presenting at conferences and doing cross-institutional research projects.

Time-Based Art Conservators build and maintain working relationships and friendships to provide a network of care for artworks. [Head of Conservation at the Tate] Louise Lawson discussed new thinking on the tenets of friendship in the context of conservation eloquently in relation to choreographic work, A Sun Dance.

When I started studying, I thought I would be working independently surrounded by objects, rather than people. I’m now glad it’s the opposite.

What is the biggest joy and the biggest challenge of working with time-based art?

The wonderfully talented people I work with are very high on my joy list, but the biggest joy is getting one of our incredible time-based artworks onto display. From pre-prep work to seeing the audiences’ surprise and smiles when they interact with a work for the first time.

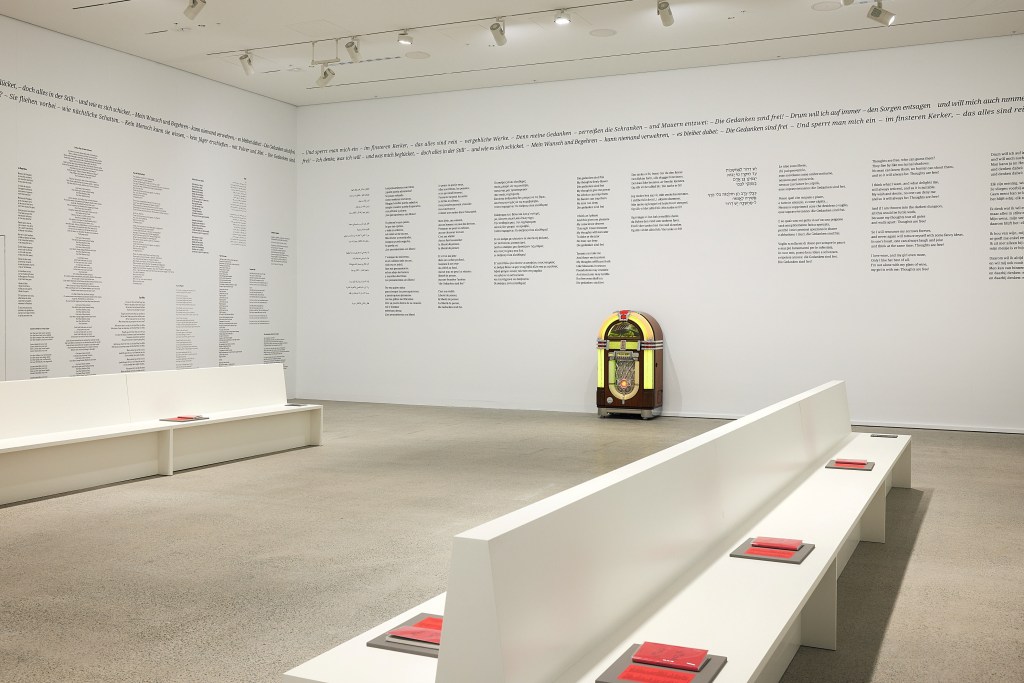

A great example is our current exhibition What Does the Jukebox Dream Of?, which features an interactive jukebox of 101 protest songs for visitors to choose from (come and choose your song!). There’s a lot of joy being had by viewers of this artwork that simultaneously addresses serious ideas about what it means to be alive at this moment in time.

Personally, I like to exchange the word “challenge” for “opportunity”. For complex works, if one component breaks down it has consequences for the entire installation. For the jukebox – Die gedanken sind frei (Thoughts are free) (2012) by artist Susan Hiller – Time-Based Art Conservators Emma Ward, Asli Gunel and I learned how to program a CD-based jukebox, decipher flashing LED codes (instruction manuals can be cryptic), loosen a stuck gripper arm and burn 100 gold archival CDs, and we listened to five hours of playback to ensure the CDs were glitch-free. Emma worked closely with objects conservator Sofia Lo Bianco on other physical components, and ongoing troubleshooting is assisted by our indispensable exhibitions AV team. A local Wurlitzer jukebox technician (there are very few left, an almost lost trade) was sought in case the electronics require repair.

When I started in conservation, I didn’t anticipate an opportunity to get to grips with the inner workings of a jukebox! A challenge/opportunity and a joy rolled into one.

If you were interviewing someone for your job, what skills and qualities would you look for?

As time-based artworks can be technically complicated – many utilise old and new, and often obsolete, technology – I’d be looking for someone who is keen to be constantly learning, is a flexible thinker and can work well with other people. A good understanding of the ethical frameworks and guidelines conservators work within is a must.

Personally, I like a “can do” approach and the ability to examine issues from different angles. People shouldn’t be afraid to offer up ideas, but also be OK if the final solution or outcome is different to what they expected. There’s no room for ego; it’s definitely a team sport!

What do you think your role would look like in 2030?

Great question, and ultimately it will depend on the artists! What new technologies will they use? VR and haptic works are new for galleries and museums to display today, but what will be invented after that, or not yet imagined? What new skills will conservators need to keep technology-based works displayable 50 years hence? Expertise in interviewing artists to capture first-hand their making and material experience will be of great benefit to the role and to collections.

Read: My arts job in 2030

Time-based art conservation is a relatively new conservation speciality in Australia. A regular maintenance program decoupled from display schedules would benefit time-based artworks as they age, especially those affected by built-in obsolescence.

There is a global discussion about a “slow conservation” approach that I am hoping conservators in Australia can embrace. Caring for time-based artworks is as durational as the work itself is. Conservation takes time, whether providing material care, expanding one’s own practice and thinking, or building trust with artists, audiences and communities. I’m hoping time-based art conservators will continue being excellent forward-thinking art custodians by developing these aspects of the conservation field.