‘The information age has ended, and we have entered the age of noise,’ declared Eryk Salvaggio at the recent conference, ACMI’s Future of Arts, Culture and Technology Symposium (FACT) 2024, held in Melbourne (Australia), last week.

In the session titled ‘Looking at the Machine’, Salvaggio assessed the state of digital and artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in relation to how we consume images, sound, knowledge … everything that’s “out there”.

He continued: ‘The entirety of human visual culture has a new name. We used to call these collections archives or museum holdings or libraries; today, we call them datasets.’

The sheer volume of everything that’s fed to users on the internet makes it nearly impossible for humans to make sense of it. And where archivists and curators offer context to collections, AI is trained on diffusion models that ‘dissolve the images [and] strip information away from them until they resemble nothing but the fuzzy chaos in between television channels’.

Salvaggio explained: ‘We moved from the noise of billions of images taken from our noisy data-driven visual culture, isolated them and dissolved them into the literal noise of an empty jpeg to be recreated again into the noise of more meaningless images generated by AI, among the noise of billions of other images – a count of images that already overwhelms any one person’s desire to look at them.

‘Generative AI is just another word for surveillance capitalism, taking our data with dubious consents and activating it through services that sells it back to us… These algorithms manifest as uncanny images, disorientating mirrors of the world rendered by a machine that has no experience of that world.’

Nothing gets destroyed, but neither is anything honoured or elevated or valued. Nothing in the training data holds any more meaning than anything else. It’s all noise.

Eryk Salvaggio

So, whose responsibility is it to cut through the noise, specifically in our arts and cultural sectors? Critics, curators, artists, institutions? Or do we need computer scientists and data analysts to actually take the lead?

The second speaker of the session, Associate Professor at Australian National University, Katrina Sluis, tapped into this. But first, she raised concern around this growing anxiety of AI FOMO (fear of missing out).

In this article:

Are museums being exploited by AI FOMO?

Different to the fear that AI is killing creativity or replacing artists, AI FOMO treats the technology as a trend that will give institutions or creatives an “innovative edge” and, conversely, those who don’t jump on will be left behind in the abyss.

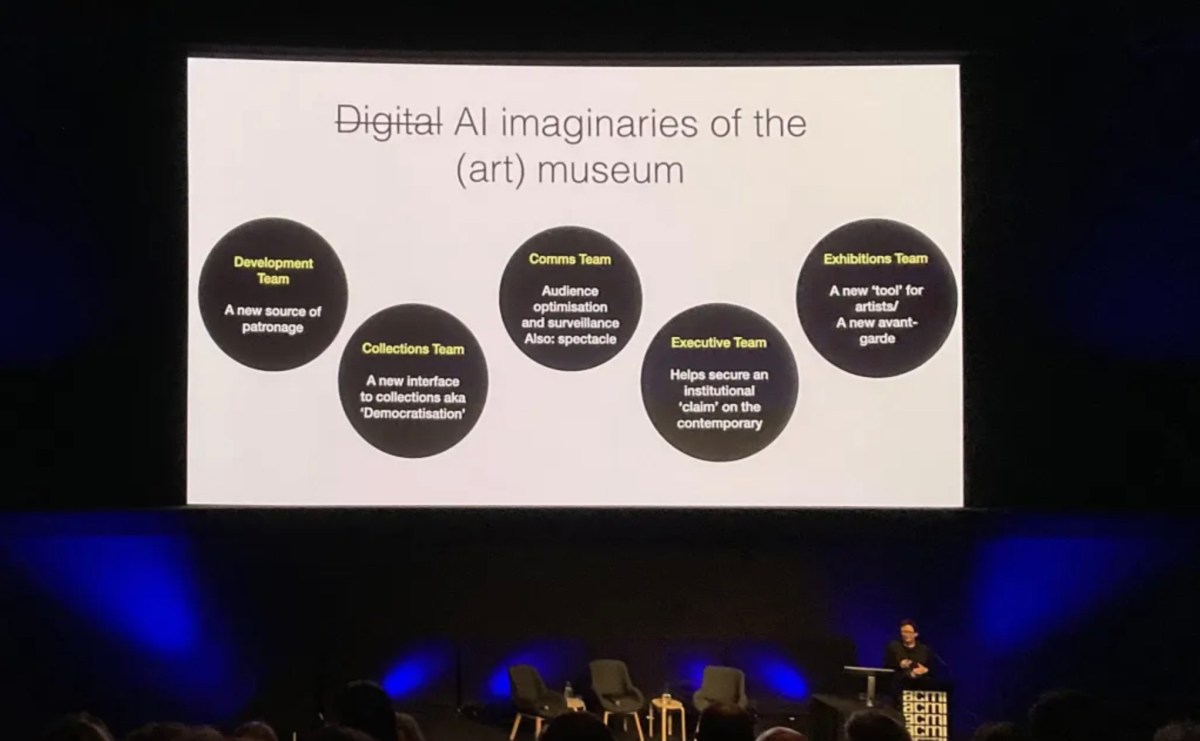

Sluis referenced the ‘AI imaginaries of the [art] museum’ across different departments to dissect this phenomenon.

‘What one person means by the digital or AI can mean very different things depending on the department [in a museum],’ said Sluis. ‘The development team sees this AI moment generally as a new source of patronage. “Why aren’t we doing a project with Google? It’ll bring in lots of money and be fantastic.”

‘To me, the executive teams [of museums] are also very excited. [They think] “We need to be doing AI; we will be really contemporary and people will realise that we are the cutting edge of this moment and thought leaders in this field.”

‘The comms team are, of course, [saying], “Great, our digital marketing can go into override, we have new analytics platforms using machine learning in order to understand visitors in the museum” – which is now a dangerous data black spot – “and we must use machine learning to extract very data point from inside the institution in order to give our audiences what they want.”

‘The exhibitions team [are saying], “It’s OK, we don’t need to think about this. We’ll just get an artist in to tell us the answer” and “Wow, isn’t this a great moment in art history?”

‘The collections team [are saying], “Well, how can we use this as a new tool of democratisation? How can we really think about the metadata?”‘

While these can begin to sound like caricatures that simplify the situation, we know there is some truth in such sentiments, and how there has always been the pressure for cultural institutions to follow the trend if they want to stay relevant and compete for attention – i.e. major drivers of AI FOMO. However, Sluis continued: ‘It’s very easy for me to stand here and critique that, but the question is, what do we actually do in this situation where institutions are trying to address this reconfiguration of the relationship between seeing and knowing audiences who are using these technologies, and trying to understand what the implications are for culture and the future?’

In 2012, Sluis was employed as the very first digital curator at The Photographers’ Gallery in London. She reflected: ‘I think they expected me to come in with a curatorial view to generate a new canon of photographic artists working with these tools that would help the institution manage this difficult transition. In reality, what we did was actually go, “This is a moment where knowledge and understanding is diffused” and practice-based research in the art museum became a really interesting place for asking questions and learning in public.’

This took the shape of engaging audiences, computer scientists, technologists, academics and more, but it also meant being open to failure as an institution and ‘reliquishing that sense of cultural authority’. Further, it involved ‘moving our attention away from the artist as a privileged site of knowledge about image culture, towards other actual agents such as computer scientists,’ said Sluis.

However, this is not to say that creativity is no longer important. Salvaggio pointed out: ‘I’m often asked if I fear that AI will replace human creativity and I don’t remotely understand the question. Creativity is where agency rises and, as our agency is questioned, it is more important than ever to reclaim it through creativity. Not adaptability, not contorting ourselves to machines, but agency contouring the machines to us.’

In saying this, Salvaggio said he is well aware of the tension between critiquing AI and incorporating it in his work as a new media artist. He quoted Korean artist Nam June Paik (often praised as the “Father of Video Art”), who famously declared: ‘I use technology in order to hate it more properly’.

Salvaggio continued: ‘Rather than drifting into the mindset of data brokers, it is critical that we as artists, curators and policymakers approach the role of AI in the humanities from a position of the archivist, historian, humanitarian and storyteller. That is to resist the demand that we all become engineers and that all history is data science.

‘We need to see knowledge as a collective project, to push for more people to be involved, not less; to insist that meaning and context matters, and to preserve and contest those contexts in all their complexity.’

Is AI shaping our future?

In Salvaggio’s view, an archive is fundamentally different to a dataset, and if museums and galleries lean too heavily into AI it could have serious consequences for generations to come.

‘Information management strategies that are responsible for the current regime of AI can be reduced to abstraction and prediction,’ he explained. ‘[AI programs] collect endless data about the past, abstracted into loose categories and labels. And then we draw from that data to make predictions. Yes, AI could tell us what the future will look like and what the next image might look like, [but] it’s all based on these abstractions of the data about the past. This used to be the role of archivists.

‘Archivists used to be the custodians of the past and curators, facing limited resources of space and time, often pruned what would be preserved. This shaped the archives and the subjects of these archives adapted themselves to the spaces we make for them… We can’t save everything. But what history do we lose based on the size of our shelves? These are a series of subjective, institutionalised decisions made by individuals within the context of their positions, biases and privileges – [restricted by] the funding mandates, the space and the time. Humans never presided over a golden age of inclusivity, but at least the decisions were there on display.

‘When humans are in the loop, humans can intervene. Today, those decisions are made by pulsing flops… There is something disturbing to me about reducing all of history to a flat field from which to generate a new future.’

AI offers ‘a seductive but dangerous promise, that is, the promise of new possibilities,’ continued Salvaggio. ‘AI offers us the possibility to… what? Opportunities for who? Prosperity for which people? Who gets to build a fresh start on stolen intellectual property? Who gets to pretend that the past hasn’t shaped the present? Who has the right to abandon the meaning of their images?

‘Of course, all of these images still exist, nothing is eradicated. Nothing gets destroyed, but neither is anything honoured or elevated or valued. Nothing in the training data holds any more meaning than anything else. It’s all noise. Images of victims and perpetrators fused together for our enjoyment as noise, tiny traces of trauma and scribes for the sake of seeing something to post online.’

It’s a chilling reality. AI-generated images and responses are true to the dataset, but “wrong” to the world.

At the same time, Sluis said there are parallels, but also tensions that are starting to emerge between the role of curation and data analytics. ‘Over the last 10 years there has been a tendency at tech conferences to tell data analytics people that they need to be more like curators. And at the same time in the cultural sphere, at least in Britain when I was there, [there are] reports by Nesta on what big data can do for the arts where curators are [saying], “Well, I’ve been asked to think a lot more like data analysts.”

‘There’s this weird miasma of curating moving in this way, being annexed into the computer lab and then back out again… Curation is being both cannibalised and valourised and intensified – it’s paradoxical.’

But at the heart of the panel discussion is that AI, in its current form and capabilities, requires thoughtful and critical human intervention to deliver results that are true to the world. We don’t need AI that serves up a generic scrape-and-vomit approach, that only perpetuates the failures of our past, disguised as access and democracy.

Read: How AI is now accessible to everyone.

Salvaggio said: ‘Humans have biases, but humans also have a consciousness. We work to raise the consciousness of people, [but] you cannot raise the consciousness of a machine. So we’ve got to raise the consciousness of those who designed them; you must intervene in the shape of the datasets. And we must propose new strategies beyond reduction and prediction to counter the hostility of building a future from the reduction of history into an infinite automated remix.’

This hope for human capacity to change the course of AI, rather than for it to generate our future, is encapsulated in Salvaggio’s closing remarks. ‘If artificial intelligence strips away context, human intelligence will find meaning. If AI plots patterns, humans must find scores. If AI reduces and isolates, humans must find ways to connect and to flourish.’

‘Looking at the Machine’ was presented on 14 February at Future of Arts, Culture & Technology Symposium 2024, featuring speakers Eryk Salvaggio and Katrina Sluis, and moderated by Joel Stern.

ArtsHub‘s Melbourne team attended in-person.