What an arresting and curious image this is, above, of one woman pinching the other’s nipple, looking knowingly at the unknown artist. Painted around 1594, Gabrielle d’Estrées et une de ses soeurs (Gabrielle d’Estrées and one of her sisters) is one of the most famous “breast paintings” of all time. According to Wikipedia, it depicts the mistress of King Henry IV of France, and her sister. What exactly are they doing? It would be completely anachronistic and cheeky to suggest they’re doing a monthly breast-check, but let’s pretend.

October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month (BCAM) and the aim is to shine a light on the devastating impact this cancer has on thousands each day. According to Breast Cancer Now organisation, breast cancer is the most common cancer in the UK with one woman diagnosed every 10 minutes (and one in seven women in the UK developing breast cancer in their lifetime).

Around 55,000 women and 400 men are diagnosed with breast cancer every year in the UK. It’s worth noting that male breast cancer is usually detected only after it has spread, which makes it harder to treat.

The good news is that due to rising awareness, and investment in breast cancer research, together with early detection and better treatment, death rates from breast cancer. An estimated 600,000 people are alive in the UK after a diagnosis of breast cancer. This is predicted to rise to 1.2 million in 2030.

What better way to remind us to check our breasts regularly than to look closely at some intriguing examples of breasts in art, from the generous bulges of the paleolithic Venus of Willendorf, to Anita Johnson’s award-winning small, soft sculpture Tenderness, made from a split cricket ball and possum fur.

Breasts in art

Whatever their changing depictions throughout art history, breasts continue to be sources of love, nourishment, eroticism and pain – not just pain from cancer and mastitis, but from growing breasts when you don’t want them, or suffering unwanted objectification or sexualisation because of them.

Breasts are just there, one more part of our shared humanity, and therefore, like everything else, worthy of artistic attention. The less shame we have about them, the better, and the more likely we are to check them out.

So check them out.

Venus of Willendorf, circa 24,000 and 22,000 BCE

The earliest known fertility figurine stands just 11.1 centimetres tall and is made of limestone. It’s believed to have been carved somewhere in the vicinity of what we now call Italy or in Ukraine. The figurine is all breasts and belly, and lacking in facial features. This “Venus” predates any ideas of that Roman goddess, but we believe she was worshipped or at least prized as a symbol of the female ability to bring new life into being, and to feed it with those abundant breasts.

Little Fur, Peter Paul Rubens, 1637

The Flemish Baroque artist Rubens painted so many curvaceous women in his time that he’s become synonymous with a certain curvaceous body shape. But this painting of his second wife, Helen Fourment, who was just 16 when they married, and who frequently served as his model, gives particular attention to the breasts, squished together by her arm and presented for the viewer. The “little fur” doesn’t cover much, and the relationship between subject and artist remains a mystery, but the depiction of rosy, rippled flesh feels warm and real and invites our gaze.

Read: New look at photography

Madonna, Edvard Munch, 1894-1895

Munch is best known for The Scream, but his Madonna paintings (this is one of several versions) are also iconic and definitely sexual. They seem to glorify and idealise the figure of a woman seen from below, as if she is in some kind of ecstasy. Her breasts are bare and her head haloed in red, but is she a saint or a demon? Werner Hofmann has suggested that the painting is a ‘strange devotional picture glorifying decadent love’.

Eyes, Louise Bourgeois, 1997

The French-American artist Louise Bourgeois made many sculptures of “eyes” in her later career, but these ones, made of black granite, with each stone measuring 160 centimetres in diameter, suggest breasts and nipples more than eyes. Standing bravely together they “see” across the grass of the Tjuvholmen Sculpture Park in Norway.

Tenderness, Anita Johnson, 2023

Australian artist Anita Johnson‘s practice is concerned with ‘the brokenness of things’. She was announced earlier this year as the winner of the 2023 Woollahra Small Sculpture Prize for Tenderness, a work made from a salvaged cricket ball, moulded and dyed leather, linen thread and possum fur. Johnson created an “object-prosthetic” by taking a cast of her own breast and using it to wet-mould the leather. In the media release for the prize, she was quoted as saying she was drawn to the vulnerability of the cricket ball in its wounded form, and the possum fur was a sculptural nod to Méret Oppenheim, as well as the possum skin blankets of her youth.

The Skywhale, Patricia Piccinini, 2013

Sculptor Patricia Piccinini, known for her surreal and hybrid creatures, designed The Skywhale hot-air balloon as part of a commission to mark the centenary Australia’s capital city, Canberra. Unveiled for its first flight in May 2013, the design received a mixed response for its depiction of a creature with five giant breasts or udders on each side. Piccinini has stated that the breasts were not intended to be sexual but to represent how whales feed their calves. Talking about her art practice on her website, Piccinini says it is ‘focused on bodies and relationships – the relationships between people and other creatures, between people and our bodies, between creatures and the environment, between the artificial and the natural’.

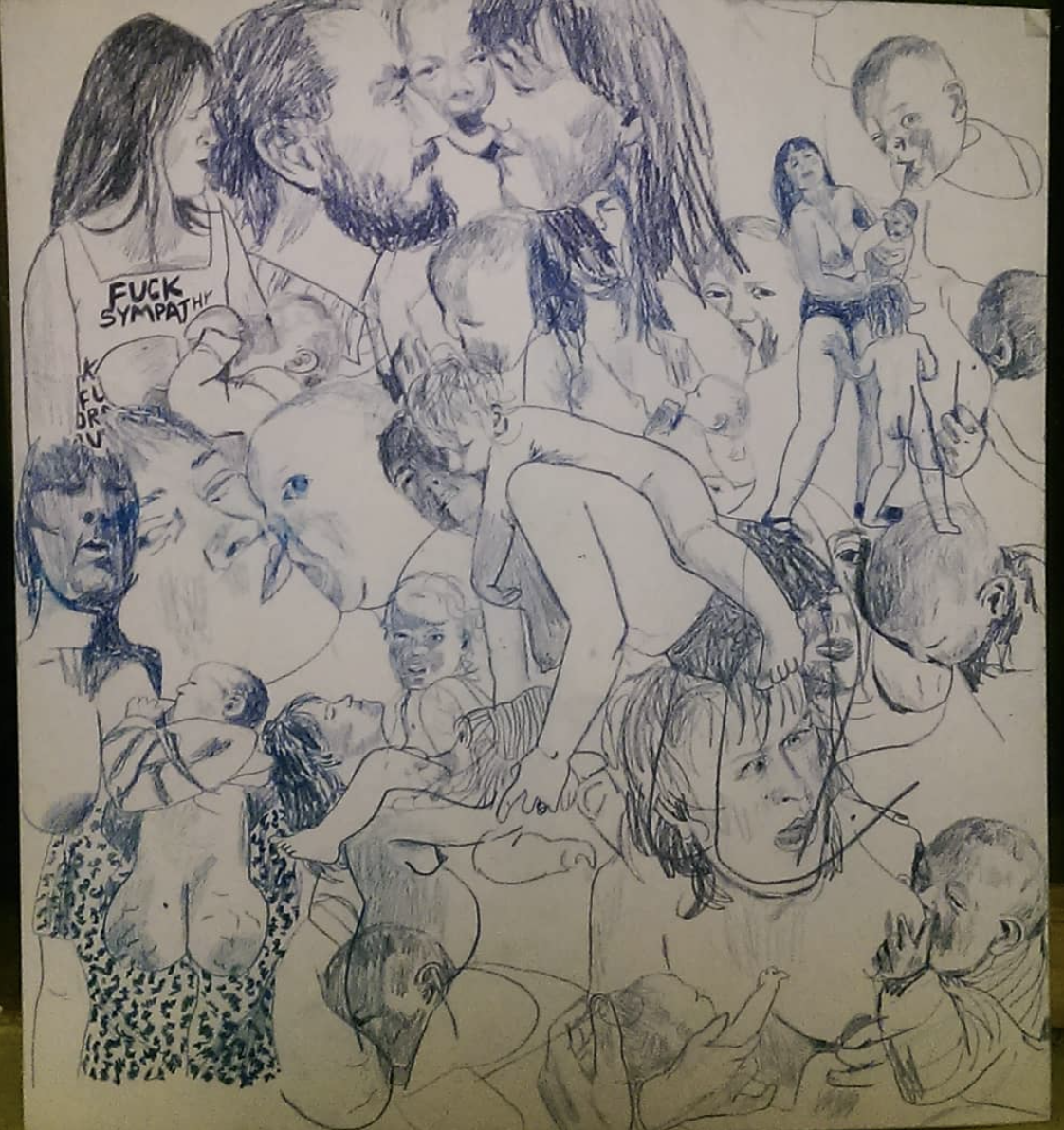

Real Life Fantasies, September Milk and Breastfeeding Drawings, Ruth O’Leary

Working in Melbourne, Australia, feminist, artist and academic, Ruth O’Leary‘s practice often involves using her own body to comment on what it is to be female in our society – to sometimes shocking or playful effect. These works include her Abortion Dress, worn recently at Victoria’s university strikes) and the video art project Peaches where O’Leary walks all over a large, reclining female sculpture, twirling with bananas attached to her bikini, against author Elena Savage’s rueful self-objectifying voiceover, reading from her book Blueberries.

Real Life Fantasies, 2017, is a photograh of a figure covered in yellow plastic with holes cut out for the large, possibly lactating, breasts to poke through, creating an entirely unsexualised and detached breast. But in other images, like the dreamy oil painting September Milk (2023), O’Leary allows the breasts to be both beautiful and functional, and also at peace; while in The Breastfeeding Drawings (2016-2-23), the breasts are presented as part of a larger picture of a woman, babies and small children, and the father and lover. These are breasts that create family.

Broken No More, Ellen Sheidlin, 2023

Russian-born photoblogger, painter, multimedia artist and Instagram sensation Ellen Sheidlin calls what she does “survirtualism”. She experiments with realism, virtuality and her dreams. This image, Broken No More, seems at first glance to be a fairly standard Sapphic photo fantasy, featuring two stereotypically beautiful naked young women pressing up against each other. On second glance, we see they are not only surrounded by small breast-like balloons, but each figure has extra breasts, fitting into the other body like pieces of a puzzle.

Australian fans of Sheidlin’s work should mark their calendars for 30 March 2024, when the artist will be in Melbourne presenting a solo exhibition at @beinartgallery.

Pink Pierce, Sarah Slappey, 2023

Brooklyn painter Sarah Slappey has said that her paintings contain ‘a quiet kind of violence’. She often depicts constrained female forms rendered in pastels, but with dangerous or disturbing details and charged objects. The breasts in Pink Pierce are about to be touched, but the presence of wire fencing and jewellery suggests pain and puncture.

Nudie and Blobs, Polly Borland, 2023

Not all breasts even look like breasts, especially when they’re seen in close-up. Melbourne-born artist Polly Borland is internationally known for her surreal and disquieting practice, spanning photographs and sculptures. She has often photographed famous people, but in the exhibition Nudie and Blobs (STATION gallery, Melbourne, January 2023), Borland’s up-close selfies of her own body, including her breasts, rendered them fleshy and, yes, blobby and unrecognisable. According to Borland’s artist statement on the exhibition (which ArtsHub reviewed here):

‘The selfie work is confronting my ageing body. They are nudes basically, so I decided to use my iPhone and do what everyone else is doing, but not beautifying or hiding anything. It’s about the body’s decay as one grows older.’

Breast Cancer Art Project – Instagram

There is something powerful and shocking about the truthful depiction of mastectomy scars. These are images of survival. The Instagram account Breast Cancer Art Project is an online platform for those affected by breast cancer to express themselves through the power of art, and a good reminder to check out your breasts, for real.

Visit the National Breast Cancer Foundation for more information about Breast Cancer Awareness Month.