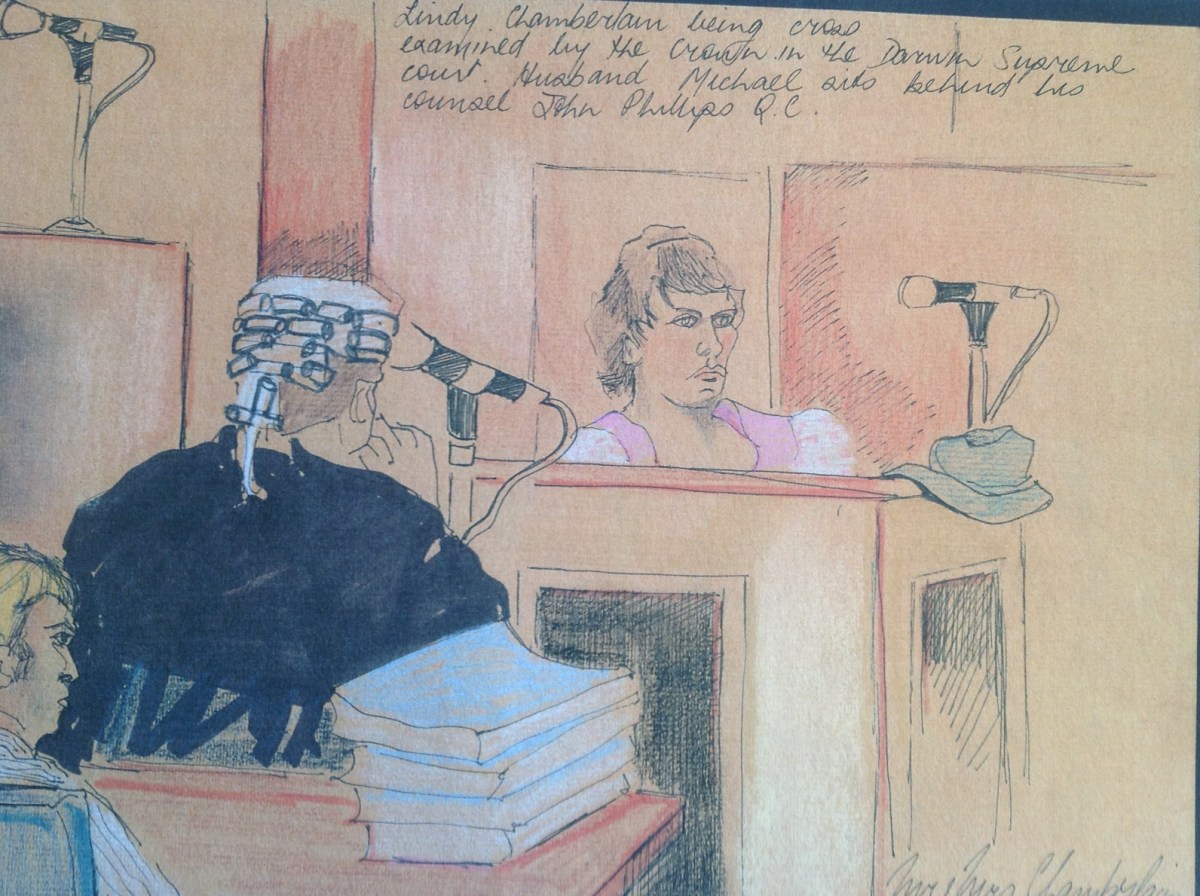

Artist Veronica O’Leary is perhaps best known – outside her exhibition work – for producing 182 courtroom sketches of the high-profile criminal trial of Lindy and Michael Chamberlain over the death of their daughter Azaria.

The disappearance of baby Azaria from Uluru (formerly Ayers Rock) on 17 August 1980 is one of the most infamous events in contemporary Australian history. Capturing it O’Leary says it was exciting but often stressful.

There has been a renewed interest in courtroom drawings in the recent month, as images by US artist Jane Rosenberg, illustrating Donald Trump’s arraignment in a Manhattan courthouse, have circulated social media, with her images making the front cover of the 17 April edition of The New Yorker – the first time a courtroom sketch has been used in such a way by the weekly magazine.

So what does it take to be a court illustrator?

O’Leary had been living in Darwin at the time, when she was appointed Court Artist for the ABC during the Chamberlain trial. They used her drawings in their television coverage of the case each night. Sometimes up to 15 of these would be flashed into the script. Later on, her suite of drawings from the trial were purchased by the National Museum of Australia, in 2011.

In 2012, O’Leary returned to her role as courtroom artist, travelling to Darwin for the fourth Coronial Inquest into the death of Azaria Chamberlain.

While this was a defining moment for O’Leary, she is also known as an arts educator, and her studio practice of landscape and still life paintings, for which is a regular prize finalist. She speaks with ArtsHub about that amazing career opportunity.

How would you describe what you do to your ‘non arts’ friends?

What I do is paint and draw as a practising visual artist, working across different mediums from watercolour, to ink, acrylic, oil paint and lino prints. Currently, I am painting small- and large-format paintings based on the table scape and food as art – a series inspired by COVID lockdown and inspired by the Dutch still life painters of the 16th and 17th centuries, like Clara Peeters, a very successful woman painter of vanitas table settings and natura morte.

What qualifications do you need for this job?

You do not necessarily need qualifications to be a practising visual artist, but dedication, commitment, perseverance and a lot of time doing the work is essential. Initially, I trained at the Victorian College of the Arts Melbourne, where I majored in painting and printmaking.

I completed my BA in Visual Arts at Darwin Community College in painting. I then completed a Master’s Degree in Visual and Performing Arts at Charles Sturt University, majoring in painting.

How did you get your start in this career?

I got my start in the job as a court artist in Darwin after I had graduated and was working as a lecturer in Creative Arts at Darwin Community College. I had never been a court artist, and it wasn’t until the ABC called for expressions of interest to be the ABC Court Artist for the Lindy Chamberlain trial in the Darwin Supreme Court, in 1983, that I started my career in this field of visual art practice.

Basically, you had to submit a portfolio of drawings of people in situ, drawn from life and on the spot. The job was to draw the participants of the court room and capture significant moments in the courtroom drama for a nightly ABC television audience.

The artist was to be in the courtroom all day drawing sketches for the news. I submitted my drawing portfolio to the ABC in Sydney and was awarded the job for the duration of the trial, which lasted for three months. This began the journey of a lifetime.

Daunting, and at times terrifying, knowing that the work was to be on national television each night and would have to be a good representation of the major players in the drama, significant witnesses and the jury. You had to work quickly, be inventive about picking key moments and the drawings had to be dramatic enough to capture audience attention and be true to the chronology of the case.

How collaborative is this job?

This job required collaboration with the TV journalists, who would have a particular pitch for each day’s events in the duration of the trial. The court drawings selected for that day would have to corroborate with the particular headline banner for that night’s news. This often meant doing 20 or so courtroom sketches for the day, from which the appropriate selection could be made. This could prove a tricky guessing game dependent on the particular dramatic turns in the theatre of the court drama.

You had to cover a lot of bases and watch, and read the playout of what was being argued in court. The essence was speed, confidence in capturing the moment, and a belief in your own ability to draw people in situ. People were moving about and you had to quickly catch their mood and likeness.

What’s an average week like?

An average week was all day in court until the session finished each day, usually about 10am to 4.30pm daily. This was a complicated process from Darwin. Because I was working for ABC television news, the broadcast had to be done with the news front person with the chosen daily drawings. The time difference between the NT and NSW meant that this broadcast had to be filmed from Darwin Court at 4pm to make the cut for the national 7.30 ABC news.

A problem sometimes arose if the court was still in session when the broadcast was sent to Sydney. If there happened to be a significant turn in the course of the day’s trial it may not have been captured by the artist, or the journalist. So that could mean a quick dash back into court for a particular drawing. This did often cause some panicked moments.

What’s the most common misconception about being a court Illustrator?

I was working for television as a court artist, so the brief was significantly different from the traditional court illustrator, doing highly articulated drawings of the courtroom with the lawyers, judge and jury represented in their respective places within the detailed architecture of the courtroom.

I was employed as an artist to give a rendition of the drama of the courtroom moments, so the focus was on the faces and posture of key players – the Chamberlains, the jury, the lawyers, the judge and, importantly, key witnesses. The courtroom sketches sought to be dramatic, show movement and capture the drama for a nightly TV audience. As no photographers were allowed in court, the drawings had to be close to life and identify the key participants in this complicated trial.

How competitive is this job?

For me the job was based on the submission of a portfolio of drawings and, like all arts jobs, highly contested.

In an interview for your job, what skills or qualities would you be looking for?

This job requires a sureness of drawing skills based on the knowledge that court drawing demands that the rendered likeness be true to life and identifiable. It demands speed of drawing, a good eye for relevant and pertinent detail, and an eye for compelling composition. It means understanding the courtroom drama and choosing the salient moments to draw for news reportage.

What’s changing in your professional area today?

I think that today some courtrooms do allow news photographers in, so the courtroom artist is not always needed. In those cases where there are no photographers present, the court artist is a very essential recorder of the courtroom facts. There is, of course, a revived interest in the art of the court artist in major trials like that of Donald Trump. The court artist can capture personality in a way the camera cannot.

What’s the most interesting thing that’s happened to you in this job?

The Chamberlain trial was one of the most publicised trials in Australian legal history, and Lindy Chamberlain became something of an enigma in Australia. The nation was divided about her guilt or innocence. It was a television spectacular, and viewers followed the saga nightly via media news, then a movie and several books.

The world of court drawing for television was exciting, challenging, often stressful, but artistically inspiring. I was invited some 30 years later to be the court artist in the Darwin Supreme Court for the Coronial Inquest, which finally exonerated Lindy and granted her pardon. This was an exciting opportunity to reconnect with ABC journalists and see Lindy finally be declared innocent of the death of her daughter Azaria

Read: So you want my arts job: Scribe

Subsequently this led to a meeting with Lindy in Sydney, where I was able to talk with her and paint her portrait. It was a marvellous meeting and talk with a truly remarkable and strong woman.

What about gender balance in your industry?

There have always been a number of women court artists. When I was doing the initial court drawings there were at least two other women in the court room drawing.

What’s the weirdest thing that has happened to you ‘on the job’?

It was on my first day on the job. I was placed in a room with hundreds of journalists and told to draw from the television screen. This was impossible. The flickering pixelated image on a screen made it an impossibility to draw from. What a panic! Thankfully, this was revoked, and we were allowed as artists into the courtroom.

The other weird thing was drawing the inside of the Chamberlain car. For a morning, the journalists and court artists had to crawl inside the car and gather images for the news broadcasts.

Veronica O’Leary has an upcoming exhibition at Aristology opens at West End Art Space, in Melbourne, 1-17 June. She is showing intimate tablescapes.