A hand darkened with soot struggles to grab falling lead ingots in Richard Serra’s three-minute film Catching Lead (1969). Sometimes the hand is victorious in capturing the commodity, but often the hand snaps shut, only grasping air. Many authors have suggested the film is about the limits of the artist’s intentions.

Understanding art production today, or of the last three years, requires getting a handle on art as a commodity among the complex market of other commodities – from steel to timber, microchips to acrylics.

The action an artist takes with a material is the first step to achieving an idea, thus what it’s made from is as important as the inspiration and result. However, when China shut down manufacturing and shipping ports due to the COVID-19 pandemic, many artists felt it before US cities followed suit.

Subsequent labour shortages, stranded shipping containers and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have further impacted the commodity trade with higher prices and unpredictable access to goods. Artists have substituted, reduced and even harvested materials from existing artworks to maintain their practice among supply uncertainty.

In 2020, US sawmills closed due to the pandemic and shipping slowed, causing timber prices to increase 288% by May of 2021. ‘People were redesigning with hollow steel when lumber [timber] prices got so bad,’ Ryan Elmendorf and Evan Beloni of the engineering and fabrication studio Elmendorf Geurts tells Hyperallergic. Ongoing labour shortages have meant timber prices only recently came off the highs.

The domino effect of timber meant steel prices jumped literally overnight. ‘Suppliers were quoting prices that would normally be good for 30 days, but were suddenly only firm until end-of-day,’ Beloni says. ‘I was quoted US$2 a pound [AU$2.90 for half a kilogram], and when I went to buy, it had jumped to US$7 (AU$10.40).’

The price movement meant fabricators either had to renegotiate project budgets or, on fixed bids, swallow the loss.

Artist Linda Fleming took delivery of stainless steel panels in 2021 in preparation of a large sculpture for an exhibition the following year, when she realised she was shy on the necessary material. In the two weeks that passed after her initial steel delivery and inquiry to purchase more, the price tripled, nearly killing the piece. ‘It made me rethink the exhibition, but I just bit the bullet,’ she says.

China and Russia are two of the three largest aluminium producers in the world. Production isn’t the issue, it’s how to get it out of either country. A 2022 JPMorgan Chase report noted air freight from Asia to Europe cannot travel through Russian airspace, and rail freight from China to Europe through Russia is met with uncertain passage and high insurance costs. With evolving global risks, aluminium is unlikely to stabilise for years, according to traders and shippers at last year’s North American aluminium conference.

Artist Pard Morrison buys aluminium sheets to make his 150-pound (68-kilogram) columns. Typically, the sheets are 60 x 121 inches (150 x 307 centimetres) in dimension, of which he says, ‘A year ago that would cost US$300 (AU$434) and now it is US$850 (AU$1230).’

When asked if he is considering substituting with another material, ‘That is my nightmare scenario,’ Morrison responds. ‘My sculptures are made to live outdoors, so steel isn’t an option because it will rust.’

Artist Wayne Brungard works with wood and bronze, and he agrees substituting another metal for bronze would degrade his work. Three years ago, Brungard was paying US$4 a pound (AU$5.80 for half a kilogram) for rolled bronze, but now suppliers are projecting US$12 to US$16 a pound (AU$17.40 to $23.15) with a three-month delay. If Brungard wants to avoid price movement between now and when supplies are available, he must make a 50% deposit. Since his average sculpture weighs 365 pounds (165 kilograms), he is now making small work from scraps.

Read: Why is the cost of art-making surging?

Many artists are being pushed to pivot and swap materials. Artist Jennifer Ling Datchuk saw disruptions to material availability as early as January 2020 as China started to shut down. Kilns, kiln parts and pottery wheels all became luxury items.

Datchuck also works with mirrored acrylic, which is typically an inexpensive material, but the price was driven up when sneeze guards were introduced in stores and schools. ‘This forced me to find alternatives. I discovered tiny gold glass mirrors like those on disco balls,’ she tells Hyperallergic by email.

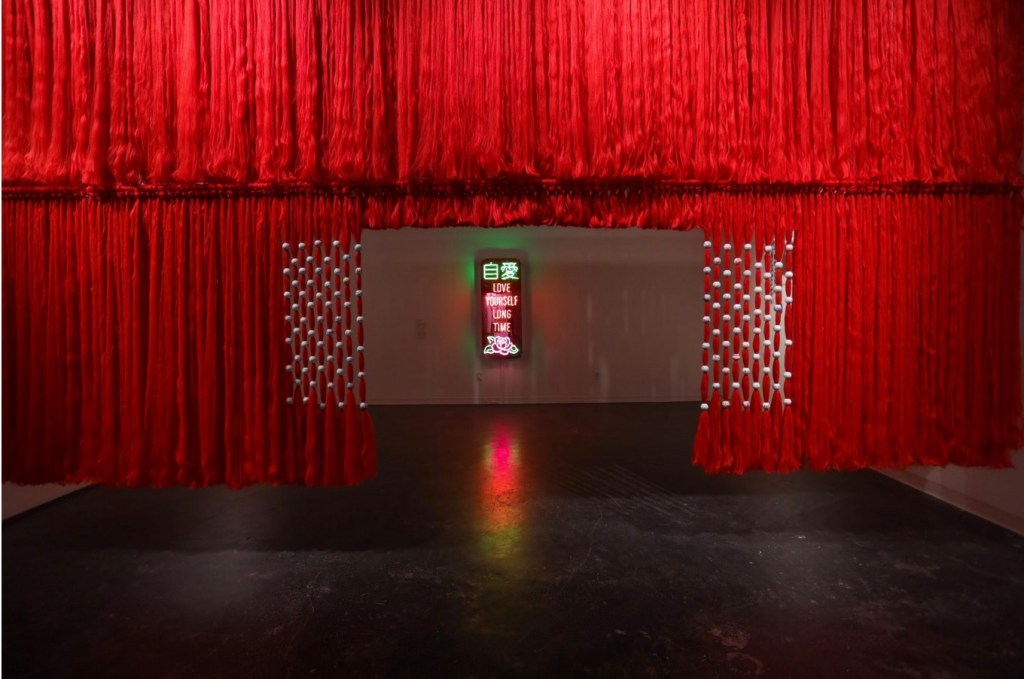

Datchuk also produces mixed media works with long curtains of synthetic hair. ‘I have a relationship with a hair factory in Shenzhen, China. There was a point when it was hard to receive goods from them. I had to take apart works I normally wouldn’t have.’

Datchuk repurposed hair from wigs in her artwork Natural Hair Don’t Lie (2016) to make Gone But Not Forgotten (2022) and Forgotten But Not Gone (2022), and she extracted red hair from the large installation Thick (2019) for use in American Flag (2020).

Historically, how and what materials artists swap communicates information on shortages and costs. During the Dust Bowl (1930 to 1936), Clyfford Still produced 19 paintings on window shades, and when raw canvas was unavailable during World War II, he created four paintings on denim. Material substitutions also expose the material intelligence of artists and craftsmen that is taken for granted by casual consumers of cultural goods. Asking an artist to swap oak for white pine or an exotic alloy for aluminium is not a simple transition. There is no bad material, but literacy with one medium does not easily migrate to another.

Read: Vegan art materials: taking the animal out of art

‘I would take the financial risk, but with the increasing cost of other materials, like plywood, I have to be more conservative with my budget,’ says artist Amber Cobb about experimenting today. Cobb encountered a shortage of polyurethane due to the 2021 Texas freeze when she was testing moulds to cast concrete forms for a commission of several small sculptures. Trusting new materials and methods is matched by questioning old ones.

Artists and fabricators that work with electronics have seen an uptick in counterfeit single-board computers called Raspberry Pi and microcontrollers called Blue Pill. The result is higher fail rates, mismatched specifications and reduced adaptability.

Not every artist contacted for this article has met obstacles in recent years, and certainly not artists with deeper pockets. Does Simone Leigh lose sleep over the rising cost of bronze, and does Yayoi Kusama break a sweat over the price of mirrored acrylic?

In 2008, Jeff Koons exhibited his monumental steel sculptures on the roof of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York right before the economy crashed. Steel prices today are hovering at prices similar to 2008, yet no published reception of that show addressed the incredible cost of materials for fabrication.

Artistic skill and concept transform a medium, but material has incredible agency. The wonderous question ‘how did they do that?’ in art circles and among enthusiasts may soon refer to more than the finished work.

This article was originally published by Hyperallergic on 11 January 2023. Some language and data have been adjusted to Australian vernacular.