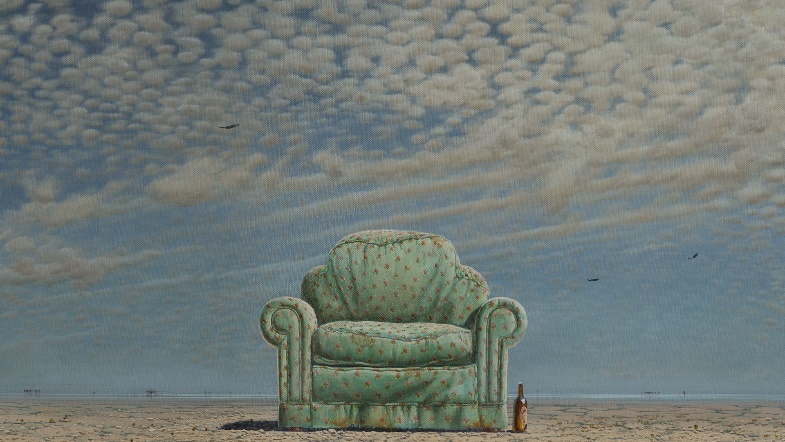

Tim Storrier is a name familiar to visual arts circles in Australia – a multi-award winner with a commercially successful international career – he was even awarded an AM (Order of Australia) for his services to art in 1994.

He is, however, less well-known within the spectre of theatre. This week, Artistic Director of Queensland Ballet Academy, Li Cunxin AO, announced Storrier’s artworks would be used in the forthcoming Summer Soirée.

Li Cunxin AO: ‘The vision behind Summer Soirée has always been about collaboration across different mediums – art, music, and dance – providing a unique platform for our next generation of young dancers, who are on the cusp of their careers.’

It prompts up to take a fresh look at the collaborations across stage and disciplines.

Read: Career spotlight: Set designer

Long history of visual artists designing for stage

The relationship, or pas de deux, between choreographers or theatre directors and visual artists is nothing new. It has emerged in parallel with many art movements, with well-known artists designing for dance, theatre and opera productions since the turn of the century.

Perhaps most famously there is the Ballets Russes – known for their avant-garde productions lead by impresario Sergei Diaghilev, at the height of Modernist thinking.

Diaghilev commissioned artists such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, Kandinsky, Giorgio de Chirico, Juan Gris, Sonia Delaunay, and Joan Miró, among others, to produce sets, costumes and promotional ephemera – not wanting to be limited by anything, and embracing a new artistic fusion.

That unique cross-discipline experimental practice was celebrated in the exhibition Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballet Russes at London’s V&A Museum in 2010. Art Historian John E Bowlt wrote in the exhibition’s catalogue that these artists ‘transcended the frames of their studio paintings to use the theatre as a laboratory of material forms.’

Any consideration of the relationship between dance and modern art is likely to begin with the Ballets Russes.

Elephant, blog

What Diaghilev instilled was a sense of trust and chance – be it working with dancers of artists. What has followed is a bond across more than a century of collaborations which is clearly still very much alive with this latest pairing of Storrier’s work.

It’s also apparent in Australian artist Sally Smart’s practise, as she continues to blur boundaries between stage and art studio, building on more than a decade’s work in this space.

There is also Ken Unsworth, whose sculptures and installations bleed and blur across the disciplines with a long term relationship working with dancers and composers.

Read: The artist as patron (Ken Unsworthy on commissioning theatre)

8 famed examples of artists collaborating onstage

1. Picasso and Ballet Russes (1910s and 1920s)

Picasso worked on six productions for the Ballets Russes, however it is Parade (1917) that is perhaps his most celebrated. Picasso was invited by playwright Jean Cocteau in 1915 to conceive the sets and costumes for the production, at a moment when he was shifting styles from ‘more analytic cubism – portraits and still lifes — into fantasy …In his designs for the 1917 [dance work] one can trace his shift from depicting Saltimbanque circus communities (the curtain design) to exploring cubist shapes (the costumes),’ explains the blogger Elephant.

2. Sidney Nolan for Kenneth MacMillan’s The Rite of Spring (1962)

This pairing wasn’t exclusive to European trends. Sidney Nolan did his first theatre commission in 1939, for the Ballets Russes’ company staging of Icare in Sydney, Australia.

In 1951 Nolan emigrated to Britain where he created his most famous theatre design in 1962, for The Royal Ballet with choreographer, Kenneth MacMillan’s The Rite of Spring.

In Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring score, a prehistoric people from the forests of Northern Russia sacrifice a virgin to the cosmic forces. MacMillan chose to flip the hemispheres, with Nolan overlaying his design with tones of Aboriginal Australia. The dancers wore ochre brown unitards marked with handprints, and the backdrop seeming burned with vibrations of Country.

Nolan also created theatre designs for The Royal Opera’s Samson et Dalila (1981) and Die Entführung aus dem Serail (1987), directed by Elijah Moshinsky.

Listen to a conversation about the Nolan’s designs.

3. Wolfgang Tillmans imagines Benjamin Britten’s War Requiem (2018)

The Turner prize-winning photographer Wolfgang Tillmans is an unlikely choice for animating theatre, however in 2018 he collaborated with the English National Opera (ENO) to design the set for Benjamin Britten’s dark and emotive War Requiem.

Tillmans told The Guardian at the time: ‘When I was invited 20 months ago to become the set designer I wondered what I would be responsible for. The artistic director of the ENO, Daniel Kramer, answered: “Every item and visual you see on stage…”’

It’s been a steep learning curve and a rollercoaster of experiences in theatreland.

Wolfgang Tillmans, photographer

Tillmans’ images take on steroid-sized proportions, captured on 8-meter tall LED walls and a 20-meter wide back projection. We have seen these same new technologies adopted by Opera Australia in recent years, which gives greater scope for companies to work with visual artists.

Tillmans describe that gallery to stage connection in an ENO Q&A: ‘I approach gallery spaces as overall installations; every picture that is in a room plays off each other and is a colour value, a tone, and has weight. Together they make an overall experience. From that spatial background, I also approach this project.’

Read the full conversation with Tillmans.

4. David Hockney’s long relationship with opera (1970s – 1990s)

David Hockney first created stage designs for Glyndebourne Festival Opera before moving to mainstages. It was Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress, performed at Glyndebourne Festival Opera in 1975 where he got the bug, returning for the 1978 Festival with the sets for Mozart’s Magic Flute.

John Cox, the director of productions at Glyndebourne from 1972 to 1981, said he felt that Hockney would have, ‘an instinctive understanding of the material.’

Hockney also designed for Parade /triple Bill (Parade, Les Mamelles de Tiresias, and L’Enfant et les Sortileges), performed at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York in 1981, and that same year also for the Met, stage designs for a Stravinsky Triple Bill.

Clearly hooked on the cross-discipline collaboration, in 1987 he did the designs for Tristan und Isolde for the Los Angeles Music Centre Opera, Turandot for Lyric Opera of Chicago in 1992, and that same year, Die Frau Ohne Schatten for The Royal Opera London.

To view Hockey’s designs for stage.

The New York Times writes of the artist’s work in theatre design, ‘For years, Mr. Hockney has driven and painted with opera blasting from loudspeakers. Now, new technical possibilities have emerged to refine the way he’s always approached design problems. And that, in turn, has made his theater work an ever more integral aspect of his own artistic evolution.’

His design models for stage have also been exhibited.

5. Isamu Noguchi for Martha Graham (1940s – 1970s)

The celebrated American modern dancer and choreographer Martha Graham, who founded her own company in 1926, loved sparse sets. Her first collaboration with the modernist sculptor Isamu Noguchi for Frontier (1935), then, was not so surprising.

It was the start of a collaboration that lasted thirty years and over twenty productions.

I felt that I was an extension of Martha and that she was an extension of me…’

Isamu Noguchi, designer

Noguchi would go on to design twenty sets over the next thirty years which were symbolic rather than decorative, to enhance the dancers’ movement, writes Tori Campbell. Their most famous collaboration was Graham’s 1944 Appalachian Spring, scored by American composer Aaron Copland.

‘The minimal set provided just enough visual information for the audience to understand the ballet’s setting, while leaving room for mystery and personal interpretation,’ explained Campbell.

I attempted through the elimination of all non-essentials, to arrive at an essence of the stark pioneer spirit, that essence which flows out to permeate the stage. It is empty but full at the same time.

Isamu Noguchi, on Appalachian Spring

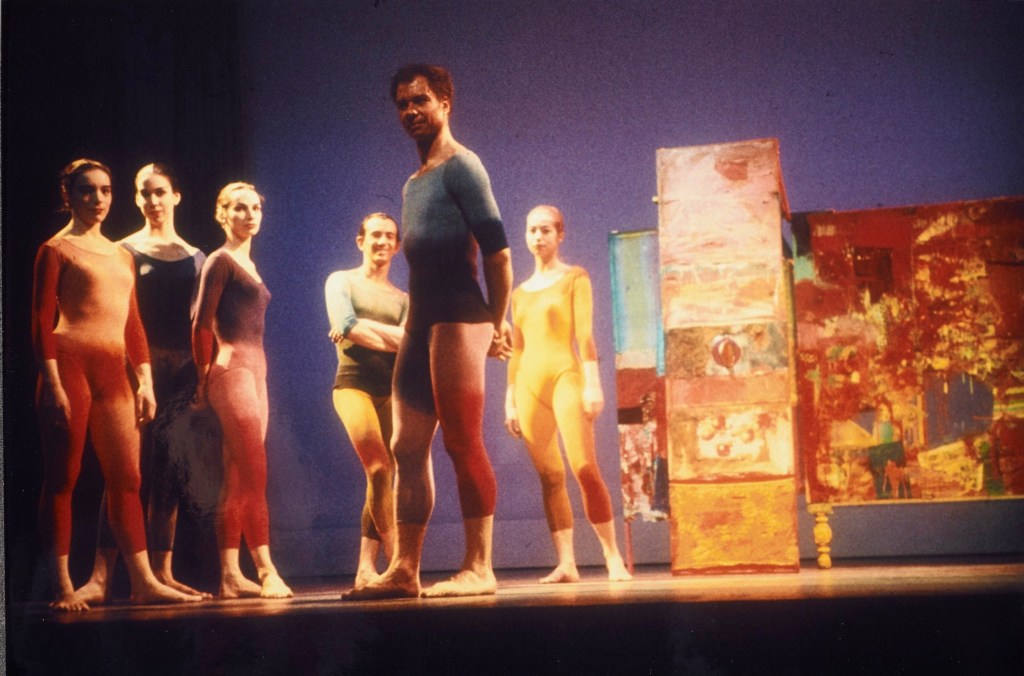

6. Robert Rauschenberg for Merce Cunningham (1950s – 1960s)

A dancer with the Martha Graham Company, Merce Cunningham went on to become one of the most influential and pioneering choreographers to date, forming his own company in 1953.

Carrying the legacy of working with visual artists forward, Cunningham worked with Jasper Johns, Bruce Nauman, Nam June Paik, Yvonne Rainer, Frank Stella, Andy Warhol, and Tacita Dean, among others.

In his earliest years as a choreographer he worked primarily with visual artist Robert Rauschenberg. Using a collapsible freestanding set for his work Minutiae (1954), Rauschenberg described Cunningham’s style as a ‘combine’ – a term he used for ‘hybridised works that blended painting, collage, fabric and sculpture.’

The Rauschenberg Foundation described his relationship with Cunningham as ‘founded on “carte-blanche trust”.

Rauschenberg began to blur the lines between his performance pieces and his other studio work, often creating works that would later become props. He often created scenery by using found objects and sounds, developing his concept of “live décor,” or scenery generated by human activity.

The artist also formed a long bond with dancer and choreographer Trisha Brown in the late 1960s, extending his bleed from studio to theatre for more than six decades.

7. Olafur Eliasson and Wayne McGregor’s Tree of Codes (2014)

Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson used a combination of mirrors and coloured screens to create the stage designs for Wayne McGregor‘s Tree of Codes ballet, which premiered in 2014.

The performance is based a reframing of a book by Polish author Bruno Schulz, which novelist and librettoist Jonathan Safran Foer cut up and reassembled to create the narrative, while McGregor created a dance for each of its 134 pages.

Eliasson told Dezeen of the project: ‘Tree of Codes addresses the book as a space that relates to our body….I look at the book as vibrant matter. It doesn’t explain ideas, but vibrates them…I tried to translate this feeling into the visual concept.’

Eliasson also developed the stage design for McGregor’s Phaedra, an opera production at the Berlin State Opera from 2007.

8. Marc Chagall’s set designs for operas across the globe (1940s – 1960s)

Chagall first worked on stage designs in 1914 while living in Russia, inspired by theatre designer and artist Léon Bakst. Many of his designs were done for the Jewish Theatre in Moscow, but after leaving Russia, he was not commissioned for another project for about twenty years.

In 1942 he got a big break. That year he was commissioned by choreographer Léonide Massine of the Ballet Theatre of New York to design the sets and costumes for his new ballet, Aleko. It premiered the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, where Diego Rivera was in the audience. It then moved to the Metropolitan Opera in New York.

Then, in 1954, he was engaged as set decorator for Australian choreographer Robert Helpmann’s production of Rimsky-Korsakov’s opera Le Coq d’Or at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, but he withdrew. The Australian designer Loudon Sainthill was drafted at short notice in his place.

The peak of his work in theatre came when he returned to Paris and designed the sets for the Paris Opera’s production of Ravel’s Daphnis and Chloë in 1958.

He later painted the ceiling of the Paris Opera (1964), and soon after that installed two gigantic murals alongside the New York Met’s grand staircase. These staircase murals became famous again in 2009 when the cash-strapped opera house was forced to put them up as collateral.