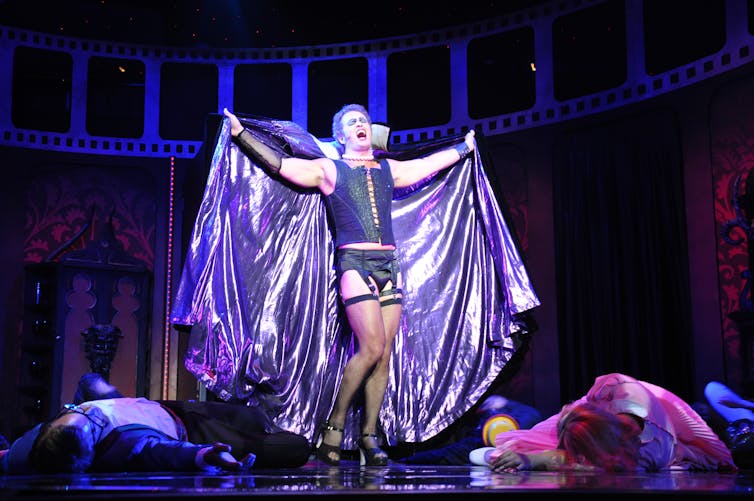

Photo: Jeff Busby

This week Victoria Police confirmed they were investigating allegations of indecent assault and sexual harassment involving actor Craig McLachlan in his lead role as Dr Frank-N-Furter in The Rocky Horror Show musical during 2014. Three actresses have complained about McLachlan’s behaviour. McLachlan, who strenuously denies the allegations, has since left the production.

McLachlan has reportedly described Rocky Horror as “a confrontational musical oozing with sexuality”. To “make” the show, he said, “actors have to perform certain actions, all of which flow from the show itself”.

While I cannot comment directly on the McLachlan case, as an actor and theatre director, I am very aware that a production’s content and style can impact greatly on the atmosphere both in the rehearsal room and on stage. It can also affect the actors’ behaviour. It is a very different experience rehearsing a deep and meaningful drama compared to a light comedy or an in-your-face, sexy musical. However, regardless of the creative environments, actors – like other professionals – are expected to treat each other with respect.

Rocky Horror’s creator Richard O’Brien told the Herald Sun last year that McLachlan “pushes the boundaries of both good and bad taste to the extremes, and wins … Of course, we have to rein him in occasionally.”

“Reining in” an actor is the responsibility of the stage manager, the director, and the producer – usually in that order. It should not be left to fellow actors to deal with difficult situations if performers “go too far”. While it is understood that a performance can “grow” during the course of a production, cast members allege McLachlan ramped up the sexual tone of his performances and prolonged intimate scenes with them.

Most actors work under the Performance Collective Agreement, a contract that states “no performer shall alter his/her part or omit any portion thereof without the express permission of the Employer or its representative”. Correct protocol is to ask permission of a fellow actor if trying something new in rehearsal. Once in performance, changes need to be approved by the director and discussed with fellow actors.

Directors usually recognise that sensitive scenes need to be talked through with the actors involved to acknowledge any levels of discomfort. If material is confronting or involves physical contact, great care needs to be taken to counsel the cast about protocols and the need for sensitivity. If sex scenes or nudity are required this is disclosed at the time of the initial auditions.

Still, although theatre etiquette is taught in drama schools and acted upon by most practitioners, it can be difficult to enforce.

Craig McLachlan performing as Frank-N-Furter in Perth in 2014. Angie Raphael/AAP

Boundary blurring

One of McLachlan’s accusers said she felt his raunchy role on stage in the highly sexualised show was “was creeping into backstage behaviour”. Theorists of acting acknowledge a phenomenon known as boundary blurring, in which emotional connections to a role spill over into everyday life as a result of actors transforming themselves and engaging in words, actions and feelings that are not their own.

For instance, psychoanalyst and actor Janice Rule writes that “living oneself into the part” can make the separation between on and off stage extremely difficult. Cast and crew often reinforce this, she argues, by treating actors on stage and off as if they were their characters. She maintains that the process of steeping oneself in a character day in and day out can train actors to become more like their characters and less like themselves.

As a result of such “hangovers”, it is important for actors to “de-role” after a performance – but this is not something they routinely do. In my experience, actors are quite diligent about “warming up” beforehand but almost never “cool down”. I recently researched the stresses incurred by acting students at leading Australian drama schools and most teachers I interviewed said their students did not take the time and space to separate themselves from their roles. And the 2015 Australian Actors’ Wellbeing Study found that almost 40% of actors surveyed had difficulty shaking off intense emotional and/or physical roles.

I have long advocated the adoption of cast debriefing sessions after performances to help in the separation of role and self. There are many other de-roling strategies such as consciously disrobing in order to let go of the costume and the character or participating in a “stepping out” process. But it is a rare cast prepared to participate in such closure rituals – going to the bar for a drink seems to be the preferred form of de-roling.

Sexual harassment in theatre

A recent survey by MEAA’s Actors Equity branch found at least 40% of respondents said they had experienced sexual harassment in theatre. More than 60% said they had been bullied and 47% said the situation was not handled well – indeed for many, it got worse after they raised the matter.

Australian clinical psychologist and actor Sarah Borg, co-chair of MEAA’s Equity Wellness Committee, told me this week she was infuriated by how often performers who reported their experiences ended up feeling blamed, disbelieved, silenced and even punished for their disclosure.

It would seem that disclosure processes need to be clarified and the chain of responsibility in theatre productions more clearly delineated. For example, who do I complain to and what can I expect that person to do in response? Claims of harassment must be investigated promptly.

![]() The McLachlan case involves very specific allegations of inappropriate behaviour. Regardless of its outcome, it has thrown a spotlight on the question of boundaries on and off stage and the need to enforce them more vigorously. Roles played on stage should be left on stage.

The McLachlan case involves very specific allegations of inappropriate behaviour. Regardless of its outcome, it has thrown a spotlight on the question of boundaries on and off stage and the need to enforce them more vigorously. Roles played on stage should be left on stage.

Leith Taylor, Casual lecturer W.A.Academy of Performing Arts, Edith Cowan University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.