Image: Installation view of Del Kathryn Barton: The Highway is a Disco at the Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia, 17 November 2017 – 12 March 2018. Photo: Tom Ross © Tom Ross.

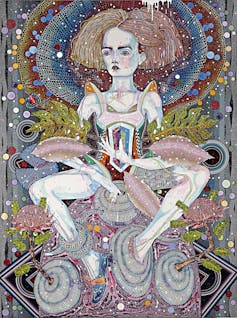

Powerful female sexuality is the essence of womanhood as imagined by Del Kathryn Barton in The Highway is a Disco exhibition at the NGV Australia. Perhaps best known for her intricate and colourful paintings of women with shape-shifting bodies and cool, detached faces, this exhibition sees Barton work across a multitude of media and explores many facets of female sexuality.

Del Kathryn Barton, openly song, 2014, private collection, Melbourne. © Del Kathryn Barton

In addition to the paintings, dating back to 2005 but including recent works from 2017, there are works on paper, a series of collages, fabric works, sculpture, and RED, a film starring Cate Blanchett and the artist’s own daughter.

The paintings are visually stunning, painstakingly executed and invite exploration. Spanning over ten metres, sing blood-wings sing is Barton’s newest one and was apparently executed while listening to Peter, Paul and Mary’s Puff the Magic Dragon. Over five panels, five of Barton’s translucent, tight-lipped females sit astride/merge with/copulate with doe-eyed dragons in a pulsating, whirring night sky.

Barton has sometimes been accused of substituting surface for substance in her paintings. The eye is driven in a relentless frenzy around each of the panels, unable to rest anywhere and the viewer is constantly challenged to create meaning from the teeming symbols and motifs. The cool, almost haughty demeanour and elongated gesturing fingers of the women are at odds with their bodily ecstasy. The women of Barton’s paintings live in their own imagined universes of the mind, realms within which they are fully in control.

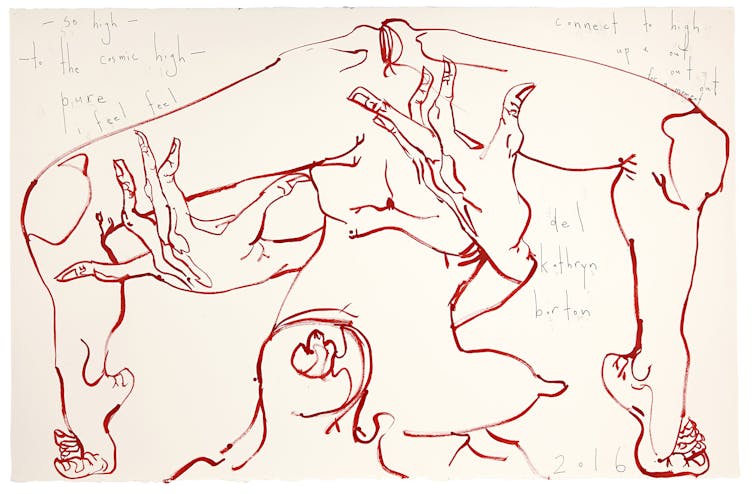

In contrast to the tightly controlled paintings, the volcanic women series of drawings (2016), elicited in lush, loose, red lines, shows distorted and headless female forms at the moment of toe-curling orgasm, erupting powerfully with the earth’s life forces. This is woman at the moment of transcendence of the rational, merging with the raw convulsing earth.

Del Kathryn Barton, volcanic woman 2016, from the Volcanic women series 2016, Collection of the artist. © Del Kathryn Barton.

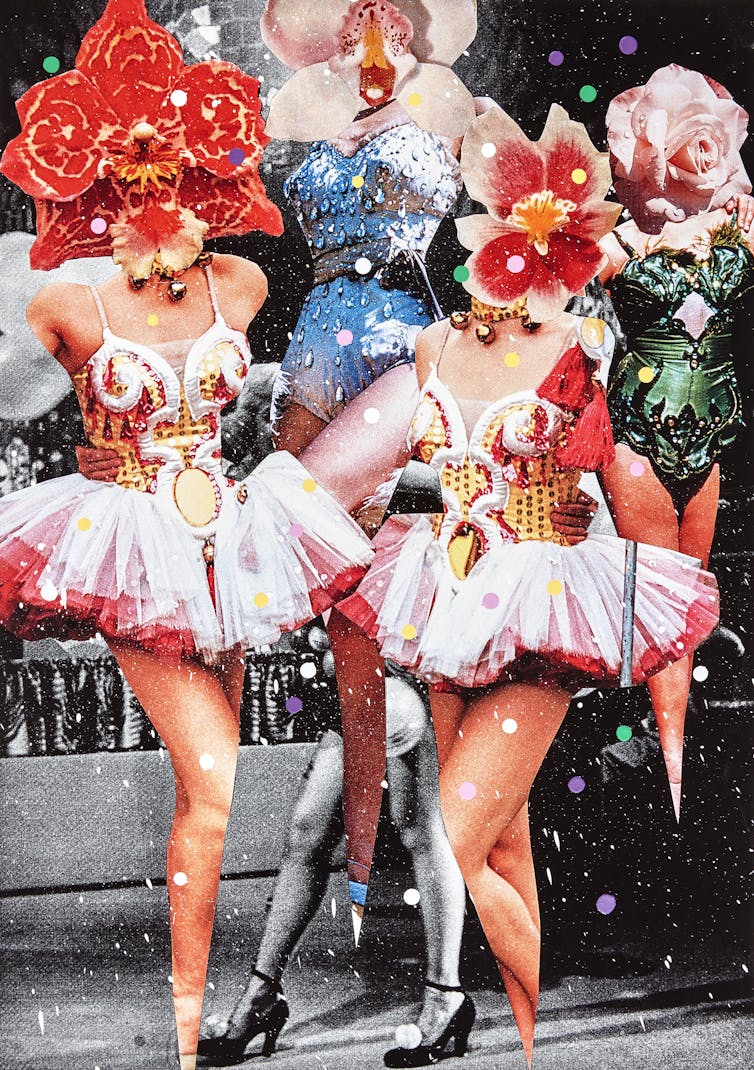

The collages in the 2017 series inside another land frequently feature the posed female body morphed with orchid flowers inviting the possibility of penetration and fertilisation. The fetishisation of breasts and eyes carries over from the painted works as the bodies, often in suggestive or explicit poses, are de-personalised and exhibited as hybrid specimens.

Del Kathryn Barton, inside another land 2017 (detail), Collection of the artist. © Del Kathryn Barton.

The small Louise Bourgeois-inspired sculptures of the penis room are complemented by the large sculpture at the foot of your love, created in response to the terminal illness of Barton’s mother.

A large Huon pine vulval conch shell, appearing deceptively soft and malleable, emits a truncated umbilical rope. This lifeline cannot be reached by the pair of impossibly outstretched hands on the ground. A silk handkerchief, printed with Barton’s collaged images, forms a backdrop, perhaps representing the traditional feminine as well as the tears of grief to be cried over the loss of a mother.

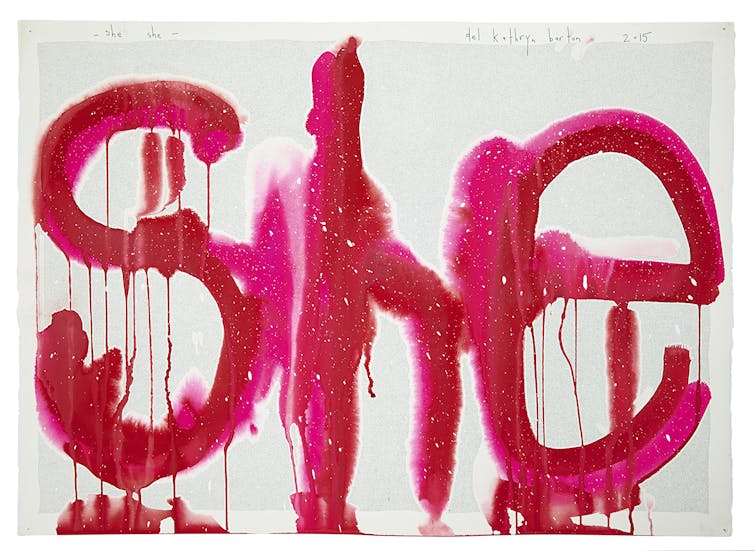

Barton, while rejecting claims to poetic mastery herself, is enamoured of words and their shifting meanings and slippery evocations. In her studio practice, she scribbles words on the walls for inspiration, and handwrites her titles into her works.

Del Kathryn Barton, mud monster 2014 (detail), Collection of the artist. © Del Kathryn Barton.

Possibly one of the least successful parts of this exhibition is the mud monster series of 2014 in which blood-red words drip and dribble on paper, emerging from a sea of black-and-white bubbles. Hung on a wall of photographic eyes, there is nothing very moving or profound here and, along with the expletives, it has all been done before and could possibly remain a part of the working process.

The 15-minute movie RED, screened in a darkened room with soft red pods for seating, is billed as a highlight of the exhibition and is Barton’s first foray as a film director. While full of striking images that make for great stills and with strong performances by the cast, it works less well as a film and lacks subtlety, clarity and nuance.

Del Kathryn Barton, still from RED 2016, Collection of the artist. © Del Kathryn Barton.

This curious choice of subject matter highlights cultural ambiguities over female sexuality. The empowered female protagonist, juxtaposed with a female redback spider, shreds her power suit with scissored hands to reveal that she is encased in a blood-red net. She both struggles to release herself from it, and writhes in sensuous agony as she entrances and ensnares her male victim.

The female entices and bewitches a somewhat passive male, controlling the encounter and leaving him dead at its conclusion, as occurs when redback spiders copulate. We are shown that she has taken his seed through somewhat hackneyed images of swimming tadpoles, and a daughter is born.

Two possible take-home messages are that men are only needed for their seed; and that sexually powerful women are predatory, violent and ultimately deadly. In fact, rather than heralding a brave new world of female empowerment, this plays on the anxieties that lead directly back to castration complex, the witch trials, and the suppression of the feminine principle in the world.

Barton is angry, at the very least. Red is the colour of fury, of blood, of sacrifice, of life and of death. In the catalogue interview with Peggy Frew, Barton states:

RED is my first consciously feminist work, and I have found myself acutely attuned to the revitalised wave of female solidarity flooding the planet at this time. I am not an angry person; I am a lover. I really am. And I am an optimist. But recently I have found myself so fucking angry! Fuck resilience! I want leadership and even supremacy for my sisters! It is our time!

Although Barton feels that she is working from a feminist perspective, the vision she expresses comes across as personalised, idiosyncratic and inconsistent – not that there is anything wrong with that.

Del Kathryn Barton, I’m going through changes 2016 synthetic polymer paint and fibre, tipped pen on canvas, 200.0 x 180.0 cm, Collection of the artist. © Del Kathryn Barton.

Paying tribute to major inspirations, the French-American artist Bourgeois and Japanese Yayoi Kusama, Del Kathryn Barton uses free association and a personal visual language influenced by Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele to express her subconscious desires and the rich fantasy life of her unbridled imagination.

Curiously, however, I find that it is the male gaze that is reproduced most often in this exhibition. Women are either de-personalised objects for display, reduced to breasts and genitalia, chilly and detached, or bucking headless cauldrons of destructive passion.

![]() Del Kathryn Barton: The Highway is a Disco is at the NGV until March 18.

Del Kathryn Barton: The Highway is a Disco is at the NGV until March 18.

Anita Pisch, Visiting Fellow, School of Literature, Languages and Linguistics, Australian National University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.