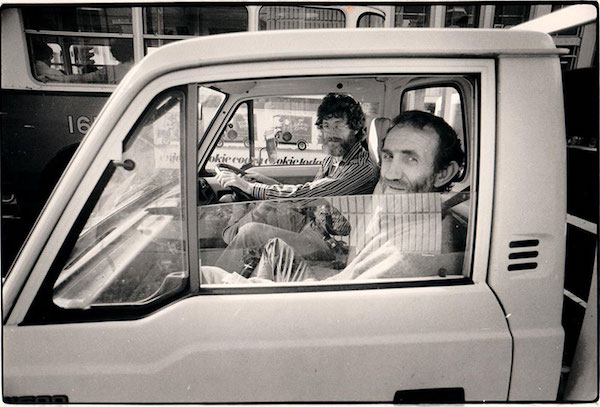

Image courtesy Watters Gallery

The highly respected Watters Gallery in Sydney recently announced it would be closing its doors permanently in December 2018. Arguably it is one of the longest running commercial galleries in Australia, owned and operated by its original three Directors since 1964 – Alex and Geoffrey Legge and Frank Watters.

But reputation and clout is not enough these days. Legge said in a formal statement: ‘We’ve discovered that our energies have not really been great enough for the demands of the art world we find ourselves in. There are new challenges and possibilities which younger people can exploit with confidence and enjoyment.’

He continued: ‘Sad news … It is such a hard decision especially in the light of the loyalty and friendship of so many people.’

Legge’s words echoed those of Jane Hait, co-founder of Wallspace gallery in Manhattan’s Chelsea, which announced its closure in 2015. At the time, Hait told Bloomberg, ‘it necessitated a reevaluation … It’s a particularly tough climate for people doing work that’s not necessarily super commercial.’

It is not an unfamiliar story. Galleries globally have been closing up shop, no longer finding the balance sheet viable, and the commercial gallery sector featuring new players and new models has become extremely dispersed.

This is particularly true in Australia, where the issue is exacerbated by the smaller scale of collecting compared to the high flying collectors circles of America and Europe.

Art critic John MacDonald was especially vocal on this point in an article in February this year, saying: ‘It’s not a question as to whether Australia wants to be part of the game, it’s whether we have the slightest chance of ever getting a foot in the door.’

He continued: ‘A young artist having a first show in Sydney or Melbourne might expect to start selling works for $1000-$2000, but in the big international galleries the starting price of a work by a young, relatively unknown artist would be more like $40,000.

‘The big-time collectors are not interested in bargains, but in status. They might buy a piece for as little as $40,000 if they believe the artist has star potential. In Australia it’s possible for an artist to never sell a work for as much as $20,000 during their entire life.’

MacDonald concludes: ‘If ever a city was made for this sort of scene, it’s brash, vulgar, money-hungry Sydney, but Australian galleries and artists are completely marginal to the international art market. In Europe and the US contemporary art is a multibillion-dollar business but in Australia – as shown by the superannuation requirements of successive governments – art dealing is hardly considered a business at all.’

A young German economics graduate/entrepreneur/ art adviser disagrees. Magnus Resch believes the entire art market could be turned into a profit-generating machine, and in 2017 released the book Management of Art Galleries, which caused a few ruffles across the global art sector.

Why? He believes that staff are underpaid, gallerists overspend on spaces, and that galleries deserve a higher cut – more like a 70/30 split with the artist for their efforts.

The new wonder model might be an economic one

From Watters Gallery in Sydney or Wallspace in Chelsea NYC, the closure of such celebrated fixtures in the art scene underscores the fact that despite the ‘unprecedented avalanche of money blanketing the contemporary art world, it’s surprisingly difficult for galleries to make money.’

That is the thought of James Tarmy, who believes that the art business is booming, but many galleries are barely getting by. Tarmy reviews Resch’s “wonder guide” with a good dose of skepticism.

Resch based his book on his own research. He sent out an anonymous electronic survey to 8,000 galleries across the US, the UK and Germany, with about 1,300 people or 16% responding with information about their revenue, number of employees, and location.

According to his results, 55% of the galleries stated that their revenue was less than USD $200,000 per year; 30% of the respondents actually lost money; and the average profit margin of galleries surveyed was just 6.5%.

Where Watters, or any other Australian gallery sits in that equation, is largely unknown as the commercial gallery sector is not know for being transparent when it comes to dollars. What we are assured is that it is a tough business, even for the deepest pockets and the most established. Biographer of the Watters story John McPhee writes: ‘Certainly the gallery would not be in existence today except for the support and accounting skills of director Alex Legge. As Daniel Thomas wrote in his catalogue introduction to the exhibition marking Watters Gallery’s first ten years, ‘For nearly ten years, from its opening in November 1964, the Watters Gallery lost money – the first year to show a profit was 1973-74…’ It took a decade to see the black.

Resch makes the key points:

Rent is too high. ‘The almost unanimous, and unquestioned, conviction that central premises in a major city are essential simply cannot be justified with an economic rationale.’ While listed as the greatest expense, Resch argues that collectors will go wherever the art is, and so paying for a premium, desirable location is therefore pointless.

Artists make too much. Galleries generally split the sale of a work 50/50 with the artist. Resch argues that given galleries cover marketing, staff and venue, shipping, and insurance costs the standard 50/50 split with the artist should look more like 70/30. He seems to have forgotten that artists pay all the costs of production of the work, and often framing/presentation as well as their share of GST on the sale.

Gallery staff make too little. Resch makes the simple point, ‘the more money employees make by doing well, the more they want to succeed, and the more profitable the gallery became.’ His argument rests in a commission incentive on sales, which is not always balanced or appropriate across a pool of staff, so arguably his point has flaws. But hey, we like the idea of better pay in the arts.

Table copyright and courtesy of Magnus Resch; Management of Art Galleries

He adds that ‘galleries are terrible at marketing and branding; they’ve done a horrible job of expanding their collector base; they’re not active enough in the secondary market; they fail to innovate their business models in any measurable way.’

It is amazing that any gallery still has its doors opens with that bleak assessment.

The alternate argument is that simply, things change with time. People get older, people’s interests change, and audiences are looking for different things. Not all projects are meant to be forever. And new galleries and models come along that grab the batton and run with it.

Doing it right is not always the right answer

At Wallspace, the gallerists’ primary focus didn’t always correlate with financial success. ‘It’s unfortunate, because galleries doing things like we were trying to do have a tough time staying in business,’ Hait said.

While extremely capable of still ‘ticking over a dollar’ and working with top drawer collectors, again there is a parallel with Watters Gallery. Partly that is because of the gallery’s integrity. McPhee writes: ‘Over fifty years, Watters Gallery has earned a reputation as being prepared to show difficult art. Certainly when first exhibited, much of what was shown was unlikely to be commercially viable, but that has never been an overriding principle determining work selected for exhibition.’

He continued: ‘Some of the earliest Australian video, installation, and performance art was shown at Watters Gallery … Work considered outside the mainstream, overlooked, or too controversial was never a problem.’

Image courtesy Watters Gallery

A gallery’s success depends on many factors, however the calibre of artists represented is key.

Watters Gallery has delivered a stellar roll call of Australian art history for more than half a century. With a focus on contemporary practice it has managed to steer clear of trends and blazing career fashion moments, carving its own brand.

Not all artists shown at Watters Gallery were young or emerging. James Gleeson joined the gallery as a 66 year old surrealist in 1981; Ken Whisson was 51 when he first exhibited with the gallery; sculptor Robert Klippel began exhibiting with Watters Gallery when he was 59.

Tony Tuckson was aged 49 and better known as a curator and art administrator when he approached Frank and Geoffrey to exhibit his work. His first show was in 1970, and fittingly is the next show at the gallery – works on paper from his estate, pages from the Sydney Morning Herald from the mid 50s to mid 60s.

It is almost like the exhibition is bookending an era, with the timing of the gallery’s closure.

Legge says of the work: ‘Tuckson’s breakthrough into abstraction seems to have occurred in works on newspaper. Certainly we should treat works on newspaper with special respect as they are likely to generate ideas that find their way into substantial bodies of work.’

One of the signatures of the gallery has been the relationships it has held with its artists, many staying with the gallery for the length of their career. But as that stable grew over the years, the difficulty of offering all an exhibition spot became increasingly challenging.

McPhee writes: ‘A solution was found in establishing a new gallery to be run by Zoe and Jasper Legge, Alex and Geoffrey’s children. The Legge Gallery was opened in Redfern in 1990. The area, like East Sydney when Watters Gallery first moved there, was rather edgy but up-and-coming.

‘However, in 2009, after nineteen years and in the less certain financial times, Legge Gallery amalgamated with Watters Gallery and Jasper joined Watters as a director. The artists coming from Legge Gallery introduced a new youthfulness at Watters Gallery. But the sudden death of Jasper just a year later, left them once again managing a large and diverse group of artists.’

The succession plan had sadly been removed from the picture.

While there are many things that could account for the closure of Watters Gallery – top heavy with staff, too large a stable, poor marketing in today’s market (a new website was long overdue and the gallery had little social media presence), not diversifying its collector pool – the greatest factor is time.

‘When we close, the gallery will be 54 years old. We had considered the idea that it may be sensible to “call it a day” when the gallery turned 50.’ Legge’s comment almost suggests last week’s news is four years overdue.

In recent weeks, individual artists have been contacted about the closure, and the journey to find new representation starts. It is a big stable of artists that Watters Gallery has today – over 40 artists to be contacted. Next comes the packing of the inventory, and then trying to figure out what to do with all those boxes of archival material in your basement. Watters dealt with that some years ago now, by donating its archive to the Art Gallery of NSW Library.

‘While it goes through emotional stages for everybody involved, we all did our very best to try and wrap up projects with artists, and make sure everyone had time to plan,’ said celebrity New York dealer Andrea Rosen when she wrapped up her gallery in February this year to focus on managing the estate of Felix Gonzales-Torres.

As senior galleries move and make was we may be seeing the changing of an era in the commercial gallery sector. One thing is clear – closing a gallery is a much more significant life change than moving from one 9-to-5 job to another, and the ripple affect is enormous.

Tony Tuckson – Nineteen works on paper opens at Watters Gallery, East Sydney, on 16 August and runs through 2 September.

Watters Gallery will close in December 2018.