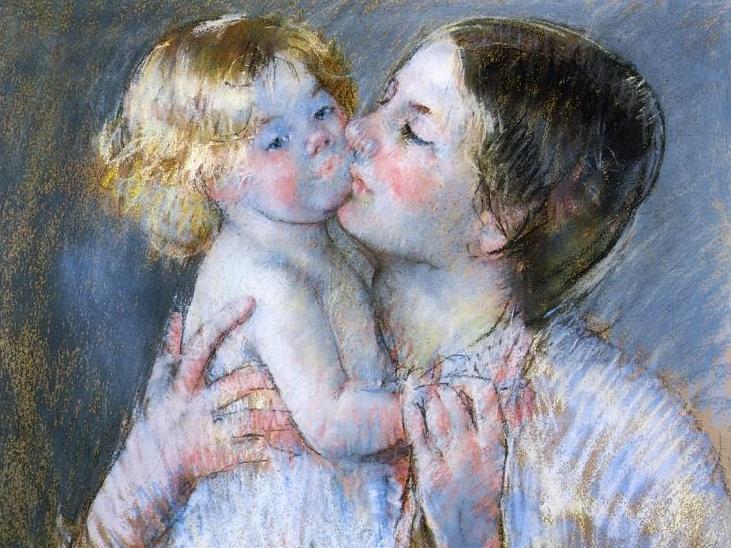

Mary Cassat, A Kiss for Baby Anne. Domestic subject matter is often blamed for the fact that Cassat is less known than her fellow Impressionists.

It was interesting to see the novelist Kamila Shamsie’s provocation in The Guardian last week for publishers to only publish books by women in the year 2018 – a provocation which has already been taken up by at least one publisher. Shamsie wrote that:

“The knock-on effect of a Year of Publishing Women would be evident in review pages and blogs, in bookshop windows and front-of-store displays, in literature festival lineups, in prize submissions.”

It’s a topic that has had some press of late. Author Nicola Griffith made headlines in late May when she revealed that “when women win literary awards for fiction it’s usually for writing from a male perspective and/or about men”.

Griffith’s findings, which are based on the last 15 years of Pulitzer Prize, Man Booker Prize, National Book Award, National Book Critics’ Circle Award, Hugo Award, and Newbery Medal, are congruent with my own research into which kinds of books tend to win literary prizes.

It is, sadly, unsurprising that male writers win more prestigious literary awards than female writers, but what is interesting is that when women do win these awards, it is typically because they write about male characters, or “masculine” topics.

Focusing on recent examples we can see this pattern quite clearly. Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch (2013) follows a young boy and most reviews of the book describe Tartt’s style as “Dickensian”; Jennifer Egan’s A Visit from the Goon Squad (2010) features both male and female protagonists as do Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge (2008) and Jhumpa Lahiri’s Interpreter of Maladies (1999).

Geraldine Brooks and Marilynne Robinson have won prizes for March (2005) and Gilead (2004) respectively, both of which focus on the novels’ male characters. The Australian women who have won the Miles Franklin for the last 20 years focus almost exclusively on capital-H “History”; Anna Funder’s All that I Am (2012); Alexis Wright’s Carpentaria (2006), Shirley Hazzard’s The Great Fire (2003) and Helen Demidenko’s infamous The Hand that Signed the Paper (1995).

Other female winners have had stories set in the rugged landscape of the Australian bush: Evie Wyld’s All the Birds, Singing (2014) and Thea Astley’s Drylands (2000); a setting which has almost become synonymous with Australian Literature, and is notorious for omitting the experiences of women.

Hilary Mantel has won the Booker twice for her novels which focus on Thomas Cromwell, and Eleanor Catton’s award winning The Luminaries (2013) also centres its story on men.

It seems that, as a culture, we are still predominantly concerned with the lives of men or in themes that we view as “masculine” or “wordly”. We still relegate women’s work to the domestic, the interior, the personal.

Author Pankaj Mishra argued in the New York Times in May that: “Novels about suburban families are more likely to be greeted as microcosmic explorations of the human condition if they are by male writers; their female counterparts are rarely allowed to transcend the category of domestic fiction.”

But in looking at the data of the history of these awards, I noticed a sharp spike in women winning these awards between 1970 and 1980, inclusive.

In this decade, the Man/Booker was awarded to five women and seven men; the Miles Franklin went to six novels by men and four by women, while in the US the Pulitzer went to six male authors and two female ones, but the period between 1970 and 1980 saw three years, 1971, 1974 and 1977 where the Pulitzer was not awarded to any book, which, according to the Pulitzer Prize committee, means that no one book was able to “gain a majority vote of the Pulitzer Prize Board”.

Interestingly many of the prize-winning books by women authors at this time featured female characters. This surge of respect for female authors happened at the same time as the formal criticism of the literary canon became widely published and new publishers such as Virago and The Women’s Press began prioritising women’s writing.

As Pam Morris wrote in Literature and Feminism (1993): “Feminist literary criticism as a recognisable practice begins at the end of the 1960s with the project of rereading the traditional canon of “great” literary texts, challenging their claims to disinterestedness and questioning their authority as always the best of human thought and expression.”

We see this in the ideological shift in the award-giving culture at this time, and it is positive proof that sustained investigation into an industry works. But it also reminds us that without this examination things quickly revert to type.

Shamsie’s provocation about publishing only female writers for a year has generated much reflection already but – over and above this – what happens if women writers produce an over-abundance of books about men? We stay mired in the same kind of ideological swamp in which we find ourselves now.

It’s not enough to publish books by women, we need to focus more on telling women’s stories. Researchers from the New York New School for Social Research have shown that reading literary fiction (over popular fiction):”enhances the ability to detect and understand other people’s emotions, a crucial skill in navigating complex social relationships”.

One of the study’s investigators, David Comer Kidd, argued that: “the same psychological processes are used to navigate fiction and real relationships. Fiction is not just a simulator of a social experience, it is a social experience.”

While these studies have not looked at gender and empathy, I would hazard a guess that a reader’s ability to view female characters as complex, layered, intellectual beings would have a profound effect on how they view actual women.

In a culture that still fetishes women’s appearance, in which women are under-represented on boards, in government and are over-represented as victims of sexual crime, knowing what women think, valuing it, is, I think, one of the most important things we can do.

This article was originally published in The Conversation.