Art exists in a social and commercial context and has long been applied to the purpose of promoting products and ideas. Manet both reflected and discussed advertising in his work. Dali both designed fashion and posed for commercials using his eccentric art. British 19th century artist Robert Burford advertised colonialism through his landscapes.

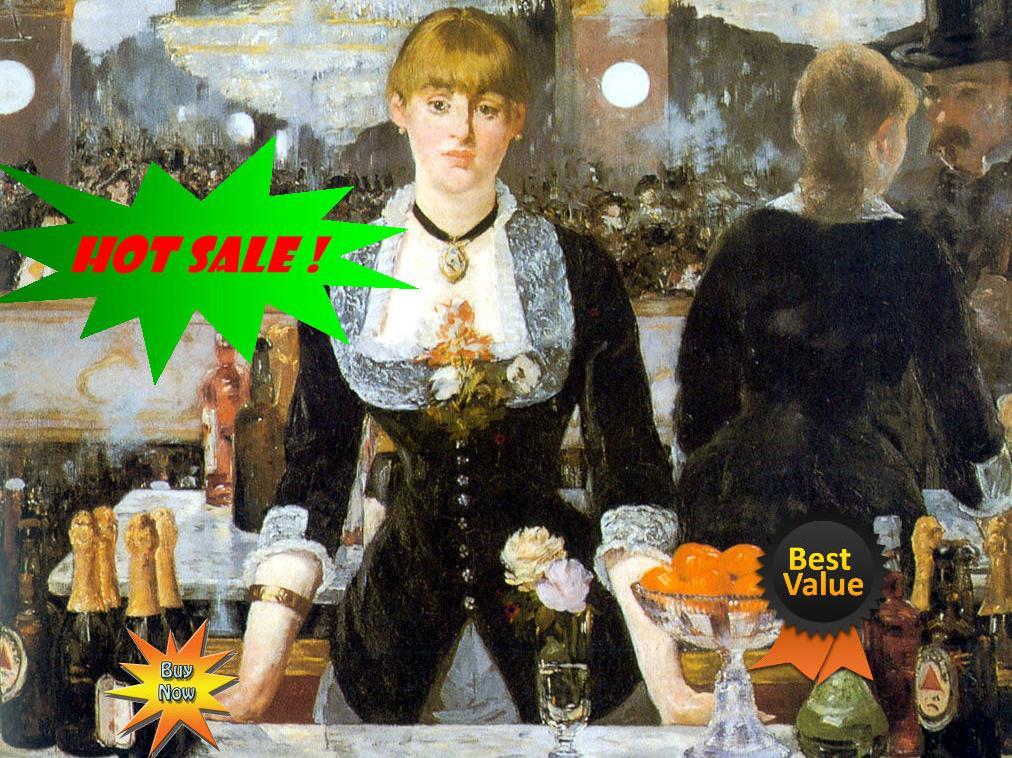

In her doctoral thesis, Eve-Anne O’Regan of the University of Western Australia identified what we would now call ‘product placement’ in Manet’s classic A Bar at the Folies-Bergère.

The alcohol Manet painted at the bar was not random but rather a selection of carefully chosen products designed to indicate the mixing of social classes that occurred at the bar: brandy because it was cheap; champagne for the wealthy; an English brand of beer rather than a German one to indicate the large number of tourists.

O’Regan said Manet used the mirror in A Bar to depict the ‘other world’ of advertising just as Lewis Carrol used the looking glass to allow Alice to access to an alternative reality.

‘Within the intrigue of its ambiguous nature A Bar at the Folies Bergere is a sophisticated reading of advertising as a central feature of the modern complex and its rituals of socialisation centred around consumption. As if he had set out to paint a microcosm of Paris as spectacle, the painting is embedded with metaphors of mass culture, commodification and the relations between people and their commodities,’ said O’Regan.

Manet also used advertising in his paintings, placing advertising posters for a circus act or for child couture strategically within his paintings to conjure aspects of the zeitgeist.

O’Regan said Manet painted advertising the way other painters depicted love or belief, using its powerful symbolic content and recognising its complex social role.

‘Manet had a penetrating measurement of advertising in all its forms both concrete and abstract as a representative aspect of the spirit of the modern.’

‘He painted the human experience of commodification by representing advertising in its naturalised context and what has proven to be enduring through the ages right up until now…in other words Manet painted the future,’ she said.

O’Regan said the way Manet used advertising exposes not only his own incisive observation of the role of particular products and posters but also the degree to which other artists must have consciously suppressed the advertising in the environment.

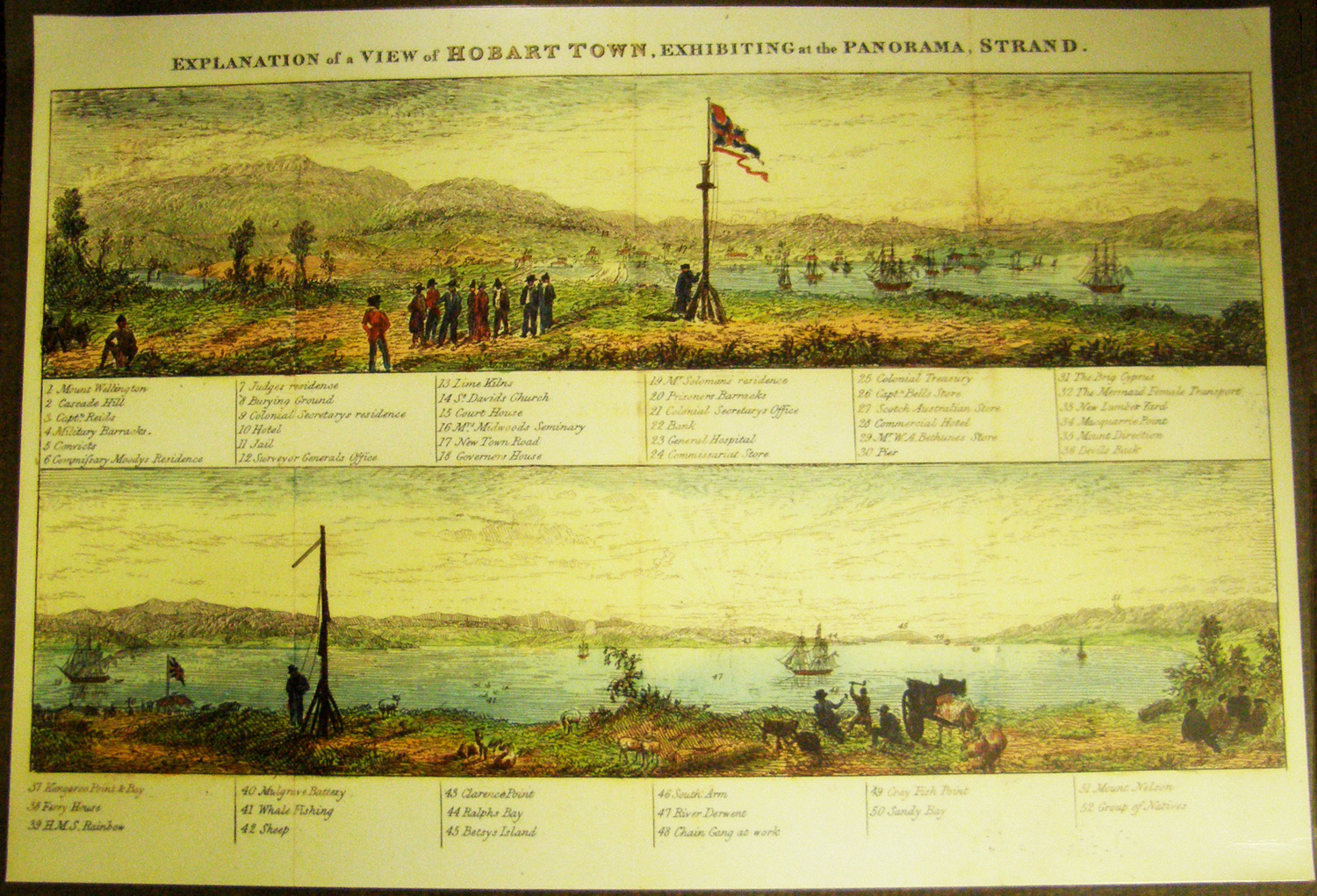

Similarly, Georgia Rouette studied the 19th Century spectacle The Hobart Panorama painted by Robert Burford and come to the conclusion that this landscape artist, too, was deeply embedded in the act of advertising. She said the Panorama was essentially a huge advertisement for migration.

A record of the Hobart Panorama from Charles Darwin’s diary

The panorama was a 360 degree experience, the ‘19th century equivalent of Imax, the ultimate immersive experience’, said Rouette. It was part of the era of spectacle which included the grand exhibitions, a form of pseudo-travel which preceded motion pictures.

‘Through the attraction of the masses…Burford leveraged the imperial subject and consequently sold imperial idealism to the masses through the spectacle.’

Burford’s panorama of Hobart no longer exists – it was cut up and sold. Like other forms of advertising, it was never meant to be a permanent work. But Augustus Earle water colours on which Burford based the panorama can still be studied as can etchings of Burford’s work. Rouette noted differences between the two as Burford heighted his subject for advertising purposes.

While Earle painted a sanitised picturesque Hobart, Burford developed signifiers to make the place seem more exotic. He added two groups of Aborigines – historically inaccurately since the Indigenous population was decimated by 1831 when the panorama was painted.

But then neither art nor advertising exists for literal truth.