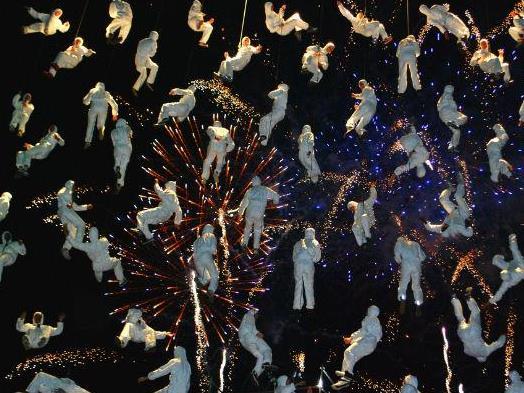

La Fura Dels Baus in the Supreme Court Gardens, at the 2010 Perth International Arts Festival.

Festivals are human rituals. It’s almost trite to say they’re as old as civilisation, but that’s something we can overlook, even when we work on them. They’re an expression of a basic human need to congregate and communicate, as much as celebrate. When we spoke about festivals during the Situate Lab, we came to a consensus – well, as much of a consensus as twenty highly opinionated people can come to – that they were moments of escape, of wonder.

Festivals are moments away from everyday life, when people are open to new ideas and experiences. You don’t have to go as far as constructing a city on a desert playa for that escape: most often, festivals come to us in the cities where we work and live, offering a new slant on the streets we know.

Festivals can also be places of extreme sensory overload, entertainment and stimulation, confusion and anticipation. It’s a tricky set of circumstances for an artist to work within – can you whisper, or do you have to shout to be heard above the din? Can you expect reflection or demand attention from an over-stimulated audience? Will the audience tune out if you tackle difficult issues or require an emotional connection?

These unique challenges are what made Situate so useful for artists (and for the festivals themselves): creating work for festival audiences requires a fresh perspective, an ability to balance your own intentions and narratives with the needs of the audience in an exceptional time and place. Situate was designed to “blow up” the creative process by borrowing across disciplines (from performance to architecture, design to academia) to expand artists’ ideas beyond the mediums and methods familiar to them.

The Lab exercises weren’t designed to have artists sketching plans for objects or installations, but instead demanded playful, inventive methods of constructing experiences for each other, building sensory moments of delight and discovery. Artist Andy Vagg built a cardboard tunnel in the dark and coached me in clawing at the other participants as they crawled through, while artist Dan Koop borrowed an armload of smart phones and recorded performance instructions for a hummed opera, which we followed, racing through the courtyard and up the stairs of the Salamanca Arts Centre.

There was an underlying push for connection, and seeing things through another’s lens: I remember artist Serena de Carvalho guiding me around the room, with my eyes closed, introducing me to the mysterious world hidden inside fuse boxes and up in the roof beams. We saw Hobart in a new way as the artists, under the direction of polychromist provocateur Sonia van der Haar, re-mapped the cityscape in colour, imagining new planes for interventions, discovering a new palette of surfaces and textures, nooks and accidental stages, to play with. Many of the exercises pushed the artists to be sensitive and receptive to each other, to operate in harmony as a group – in the Tuning exercise, they hummed and chanted in unison, pushing past the point of self-consciousness and embarrassment, and towards a commitment to, and calm within, a ritual.

Throughout the Lab I watched as the artists travelled beyond the cerebral, individual and theoretical to a place of sensation and communion. After a week of moving together, observing each other’s reactions, becoming conscious of the diversity of life experiences and perspectives within our group, I think we were all starting to appreciate the challenge of this Lab, and the festival context: while an artist creates a work to express themselves, often as part of a larger story, at festivals your greatest asset can be the unpredictable and varied responses of your audience, the emergent intelligence of the group, the way people explain and share and expand and heighten the experience for each other:

You are there and I am here / if you move this way / I’ll move that way / What I do and what I see and how I feel and where I am depends on him / And her / And you.

The process and the structure of the lab reassured us that nothing had to be perfect or permanent. Slowly, the walls filled with fantastical visions: a choir serenading a mythic white horse on a hill, a picturesque bay stained red with blood, gifts drifting down from the heavens like manna, a traveling bathtub and a dancing room.

While we experimented inside the sandstone walls of the Arts Centre, outside, Dark Mofo experimented with the form of a mid-Winter festival, offering a spectacular Bacchanal complete with dancing lasers, fire-throwing barbarian rockers, mind-bending smoke-filled chambers and a luminous, reverential stairway to heaven, daring to part the skies every night.

This eccentric, adventurous backdrop was the perfect incubator for this process: a place where anything was possible, and where audiences asked to be surprised, to see their city transformed, and new myths and legends formed.

I can see enormous potential in the Situate model: an escape from the constraints of solitary, self-driven practice, so known to many of us making or curating artwork, a sabbatical from the sensible, the familiar. In my work as a public art curator I can imagine the benefit of inviting artists to re-imagine city streets and plazas, not as places for physical installations, but as channels for connection, temples to the rituals and dynamic rhythm of society.

A Lab like Situate could give artists a new structure for engaging with our cities, and give urban planners and developers a method for investing in and supporting public interventions that empower communities and enrich the narrative of place.